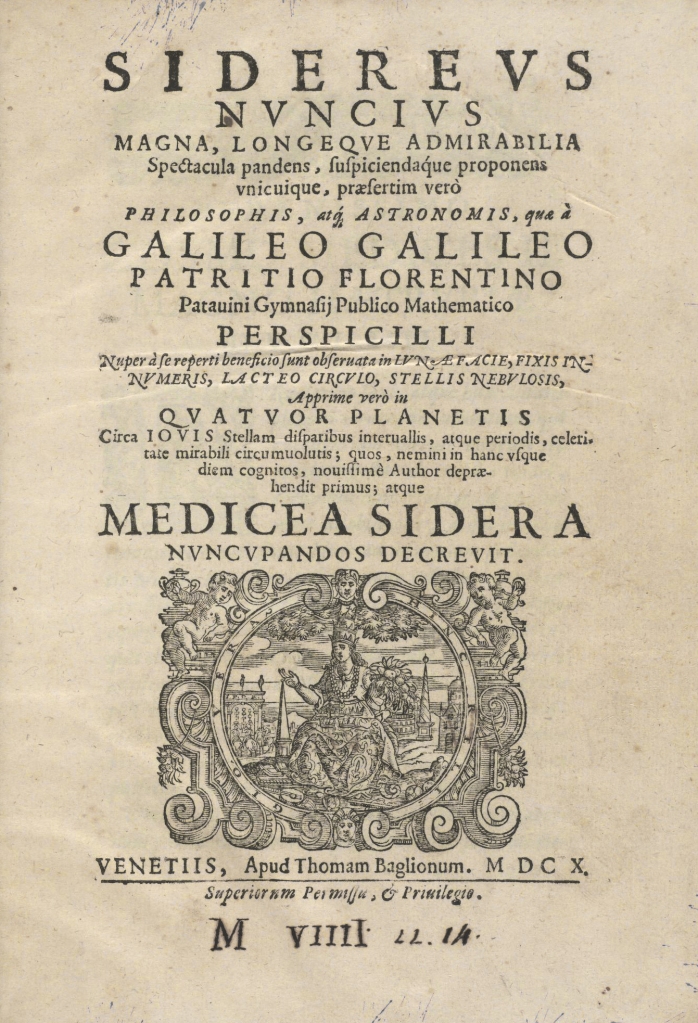

In 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius, the first publication to make known the new astronomical discoveries made with the recently invented telescope.

Although, one should also emphasise that although Galileo was the first to publish, he was not the first to use the telescope as an astronomical instrument, and during that early phase of telescopic astronomy, roughly 1609-1613, several others independently made the same discoveries. There was, as to be expected, a lot of scepticism within the astronomical community concerning the claimed discoveries. The telescopes available at the time were generally of miserable quality and Galileo’s discoveries proved difficult to replicate. It was the Jesuit mathematicians and astronomers in the mathematics department at the Collegio Romano, who would, after initial difficulties, provide the scientific confirmation that Galileo desperately needed. The man, who led the endeavours to confirm or refute Galileo’s claims was the acting head of the mathematics faculty Christoph Grienberger (the professor, Christoph Clavius, was old and infirm). Grienberger is one of those historical figures, who fades into the background because they made no major discoveries or wrote no important books, but he deserves to be better known, and so this brief sketch of the man and his contributions.

As is all too oft the case with Jesuit scholars in the Early Modern Period, we know almost nothing about Grienberger before he joined the Jesuit Order. There are no know portraits of him. The problems start with his name variously given as Bamberga, Bamberger, Banbergiera, Gamberger, Ghambergier, Granberger, Panberger and a total of nineteen variations, history has settled on Grienberger. He was born 2 July 1561 in Hall a small town in the Tyrol in the west of Austria. That’s all we know till he entered the Jesuit Order in 1580. He studied rhetoric and philosophy in Prague from 1583 to 1584. From 1587 he was a mathematics teacher at the Jesuit university in Olmütz. He began his theology studies, standard for a Jesuit, in Vienna in 1589, also teaching mathematics. His earliest surviving letter to Christoph Clavius, who he had never met but who he describes as his teacher, he had studied the mathematical sciences using Clavius’ books, is dated from 1590. In 1591 he moved to the Collegio Romano, where he became Clavius’ deputy.

In 1595, Clavius went to Naples, the purpose of his journey is not clear, but he was away from Rome for somewhat more than a year. During his absence Grienberger took over direction of the mathematics department at the Collegio Romana. From the correspondence between the two mathematicians, during this period, it becomes very obvious that Grienberger does not enjoy being in the limelight. He complains to Clavius about having to give a commencement speech and also about having to give private tuition to the sons of aristocrats. Upon Clavius’ return he fades once more into the background, only emerging again with the commotion caused by the publication of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius.

Rumours of Galileo’s discoveries were already making the rounds before publication and, in fact on the day the Sidereus Nuncius appeared, the wealthy German, Humanist Markus Welser (1558–1614) from Augsburg wrote to Clavius asking him his opinion on Galileo’s claims.

We know from letters that the Jesuit mathematicians in the Collegio Romano already had a simple telescope and were making astronomical observations before the publication of the Sidereus Nuncius. They immediately took up the challenge of confirming or refuting Galileo’s discoveries. However, their telescope was not powerful enough to detect the four newly discovered moons of Jupiter. Grienberger was away in Sicily attending to problems at the Jesuit college there, so it was left to Giovanni Paolo Lembo (c. 1570–1618) to try and construct a telescope good enough to complete the task. We know that Lembo was skilled in this direction because between 1615 and 1617 he taught lens grinding and telescope construction to the Jesuits being trained as missionaries to East Asia at the University of Coimbra.

Lembo’s initial attempts to construct a suitable instrument failed and it was only after Grienberger returned from Sicily that the two of them were able to make progress. At this point Galileo was corresponding with Clavius and urging the Jesuit astronomer on provide the confirmation of his discoveries that he so desperately needed, the general scepsis was very high, but he was not prepared to divulge any details on how to construct good quality telescopes. Eventually, Grienberger and Lembo succeeded in constructing a telescope with which they could observe the moons of Jupiter but only under very good observational conditions. They first observed three of the moons on 14 November 1610 and all four on 16 November.

Clavius wrote to the merchant and mathematician Antonio Santini (1577–1662) in Venice, who had been to first to confirm the existence of the Jupiter moons in 1610, with a telescope that he constructed himself, detailing observation from 22, 23, 26, and 27 November but stating that they were still not certain as to the nature of the moons. Santini relayed this information to Galileo. On 17 December, Clavius wrote to Galileo:

…and so we have seen [the Medici Stars] here in Rome many times. At the end of the letter I will put some observations, from which it follows very clearly that they are not fixed but wandering stars, because they change position with respect to each other and Jupiter.

Much of what we know about the efforts of the Jesuit astronomers under the leadership of Grienberger to build an adequate telescope to confirm Galileo’s discoveries come from a letter that Grienberger wrote to Galileo in February 1611. One interesting aspect of Grienberger’s letter is that the Jesuit astronomers had also been observing Venus and there is good evidence that they discovered the phases of Venus independently at least contemporaneously if not earlier than Galileo. This was proof that Venus, and by analogy probably also Mercury, orbit the Sun and not the Earth. This was the death nell for a pure Ptolemaic geocentric system and the acceptance at a minimum of a Capellan system where the two inner planets orbit the Sun, which orbits the Earth, if not a full blown Tychonic system or even a heliocentric one. This was in 1611 troubling for the conservative leadership of the Jesuit Order, but would eventually lead to them adopting a Tychonic system at the beginning of the 1620s.

Clavius died 6 February 1612 and Grienberger became his official successor as the professor for mathematics at the Collegio Romano, a position he retained until 1633, when he was succeeded in turn by Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680). The was a series of Rules of Modesty in Ignatius of Loyola’s rules for the Jesuit Order and individual Jesuits were expected to self-abnegate. The most extreme aspect of this was that many scientific works were published anonymously as a product of the Order and not the individual. Different Jesuit scholars reacted differently to this principle. On the one hand, Christoph Scheiner (1573–1650), Galileo’s rival in the sunspot dispute and author of the Rosa Ursina sive Sol(1626–1630) presented himself as a great astronomer, which did not endear him to his fellow Jesuits.

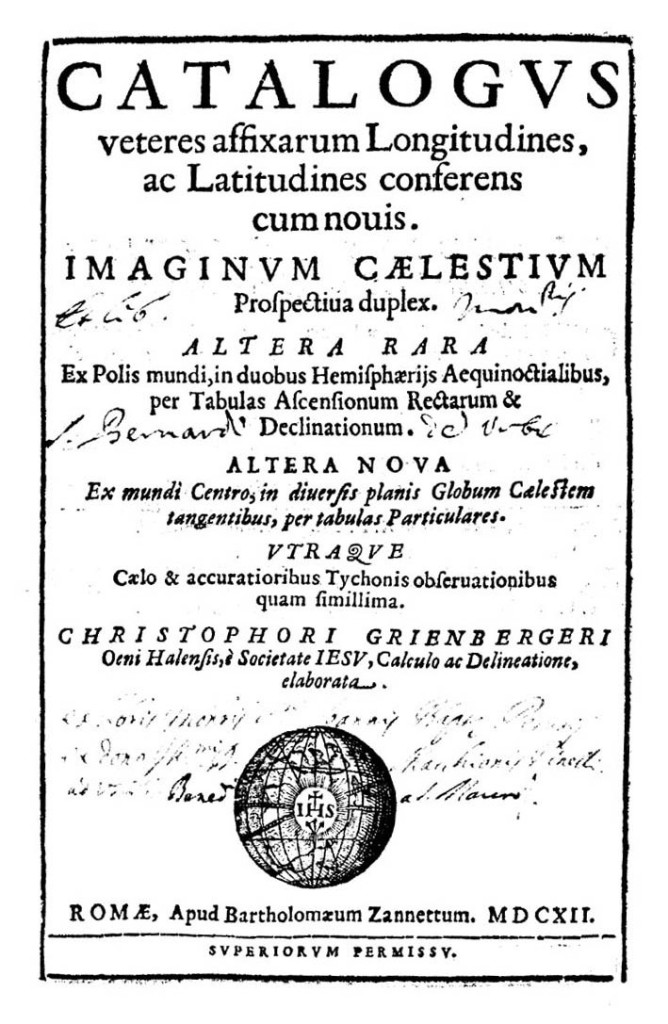

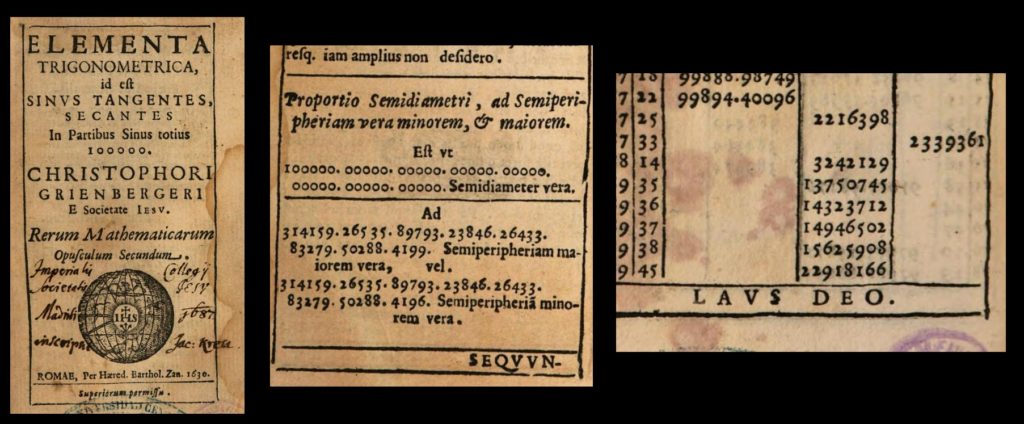

On the other hand, Grienberger put his name on almost none of his own work preferring it to remain anonymous. There is only a star catalogue and a set of trigonometrical tables that bear his name.

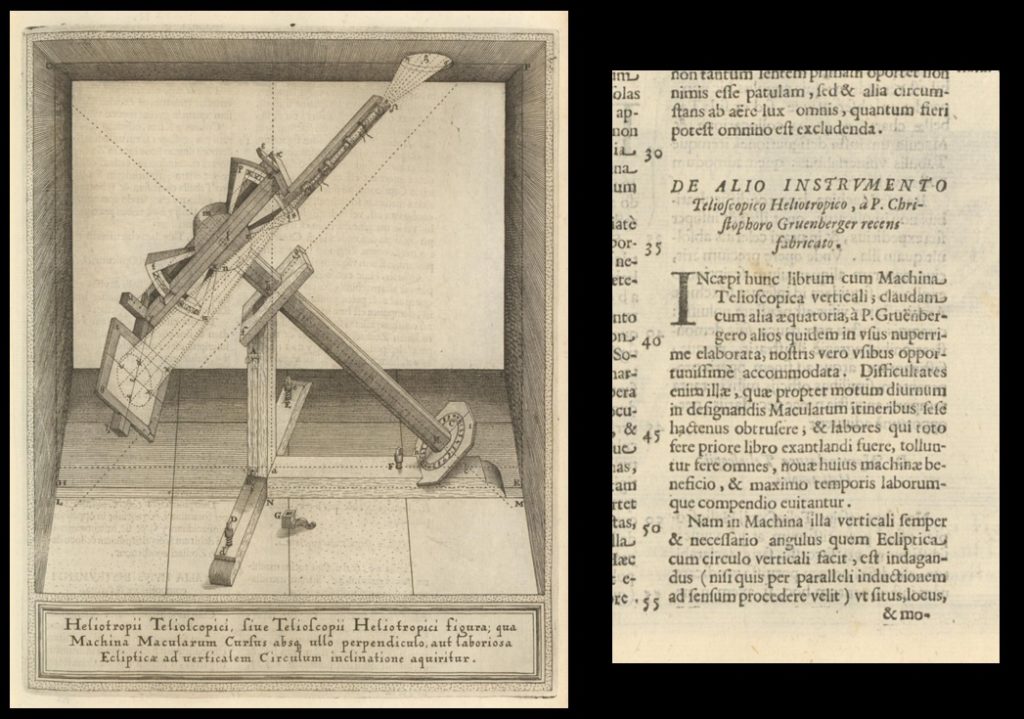

However, as head of the mathematics department at the Collegio Romano he was responsible for controlling and editing all of the publications in the mathematical disciplines that went out from the Jesuit Order and it is know that he made substantial improvements to the works that he edited both in the theoretical parts and in the design of instruments. A good example is the heliotropic telescope, which enables the observer to track the movement of the Sun whilst observing sunspots, illustrated in Scheiner’s Rosa Ursina.

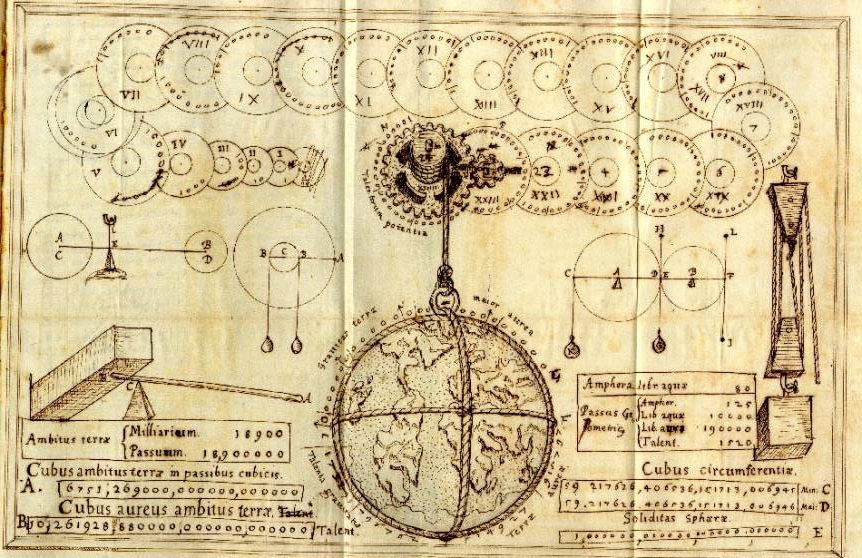

This instrument is known to have been designed and constructed by Grienberger, who, however, explicitly declined Scheiner’s offer to add a text under his own name describing its operation. Grienberger also devised a system of gearing theoretical capable of lifting the Earth

Grienberger, admired Galileo and took his side, if only in the background, in Galileo’s dispute with the Aristotelians over floating bodies. He was, however, disappointed by Galileo’s unprovoked and vicious attacks on the Jesuit astronomer Orazio Grassi on the nature of comets and explicitly said that it had cost Galileo the support of the Jesuits in his later troubles. He also clearly stated that if Galileo had been content to propose heliocentricity as a hypothesis, its actual scientific status at the time, he could have avoided his confrontation with the Church.

Élie Diodati (1576–1661) the Calvinist, Genevan lawyer and friend of Galileo, who played a central role in the publication of the Discorsi, quoted Grienberger in a letter to Galileo from 25 July 1634, as having said, “If Galileo had recognised the need to maintain the favour of the Fathers of this College, then he would live gloriously in the world, and none of his misfortune would have occurred, and he could have written about any subject, as he thought fit, I say even about the movement of the Earth…”

Several popular secondary sources claim the Grienberger supported the Copernican system. However, there is only hearsay evidence for this claim and not actual proof. He might have but we will never know.

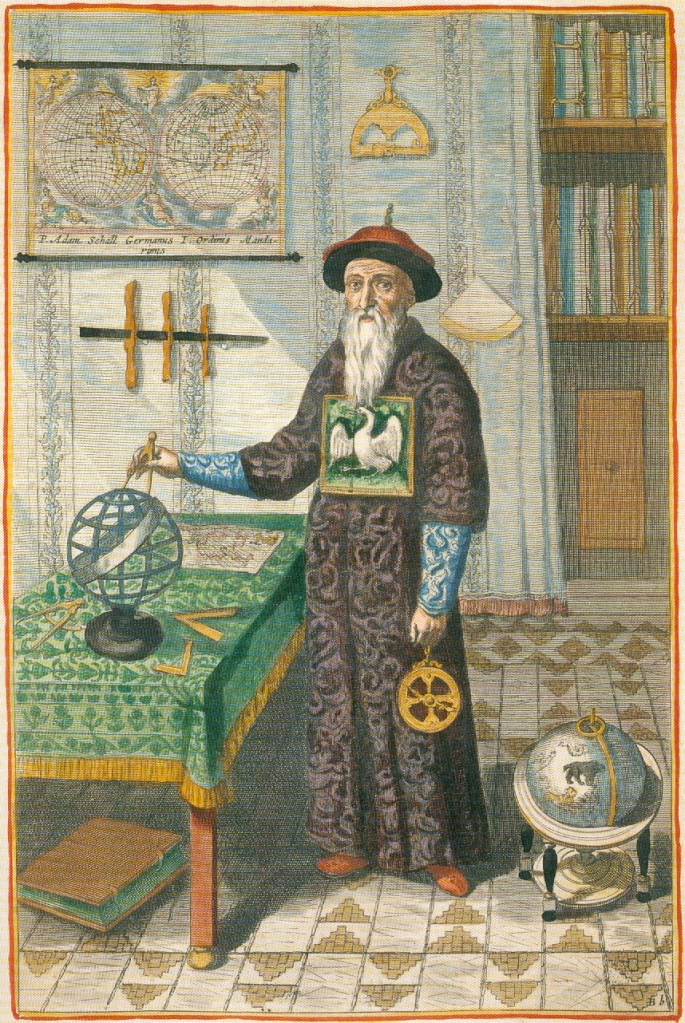

Grienberger made no major discoveries and propagated no influential new theories, which would launch him into the forefront of the big names, big events style of the history of science. However, he played a pivotal role in the very necessary confirmation of Galileo’s telescopic discoveries. He also successfully helmed the mathematical department of the Collegio Romano for twenty years, which produced many excellent mathematicians and astronomers, who in turn went out to all corners of the world to teach others their disciplines. By the time Athanasius Kircher inherited Grienberger’s post there was a world-wide network of Jesuit astronomers, communicating data on important celestial events. One such was Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1591–1666), who studied under Grienberger and went on to lead the Jesuit mission in China.

Science is a collective endeavour and figures such as Grienberger, who serve inconspicuously in the background are as important to the progress of that endeavour as the shrill public figures, such as Galileo, hogging the limelight in the foreground.