One myth in the history of science that refuses to go away is that the Catholic Church was fundamental opposed to the modern science that emerged during the seventeenth century. They even according to one prevalent theory declared war on it. This myth is of course fuelled by the equally persistent false accounts of the conflicts between the Church and both Giordano Bruno and Galileo Galilei. English scholars, not necessarily historian of science, armed with their knowledge of the reputation of the Jesuits in Early Modern Protestant England, where they were denounced as spawn of the Devil, also polemicise against them, as particularly anti-progress including science.

Long term readers of this blog will know that over the years I have posted numerous essays that try to correct this false perception both for the Catholic Church in general and for the Jesuits in particular. In fact, my very first substantive history of science post was an attempt to restore the reputation of Christoph Clavius, who introduced the mathematical sciences into the Jesuit’s educational programme, making them amongst the best educated mathematician of the period.

Long ago I read The New Science and Jesuit Science: Seventeenth Century Perspectives, edited by Mordechai Feingold, (Springer, 2003), an excellent book, in which the first essay is by Michael John Gorman, and now I have been reading Gorman’s The Scientific Counter-Revolution: The Jesuits and the Invention of Modern Science[1], of which the paperback was published this year, and which contains the essay mentioned above. This book is a must read for anybody interested in the Jesuit contribution to seventeenth century science.

I have included a scan of the back cover of the book, because the two ringing endorsements from Paula Findlen and Simon Schaffer, together with the publisher’s blurb should be enough to convince anybody interested in the topic that this is a must read, without further comment from me. However, I will, of course, make some comments.

This book is based on Gorman’s doctoral dissertation from 1999. It is not a continuous flowing narrative but, rather, a set of seven essays connected by a common theme, version of six of which have already been published in other contexts. Despite the previous publications, the book is more than worth reading, because the essays, as a whole, create a rounded picture of the Jesuits evolving role in mathematics and natural philosophy in the seventeenth century.

The opening chapter, Establishing Mathematical Authority: The Politics of Christoph Clavius, the only one not previously published, deals with Clavius’ introduction of mathematics into the Jesuits’ educational curriculum with a strong emphasis on his motivation for doing so and the political arguments he used to justify this move.

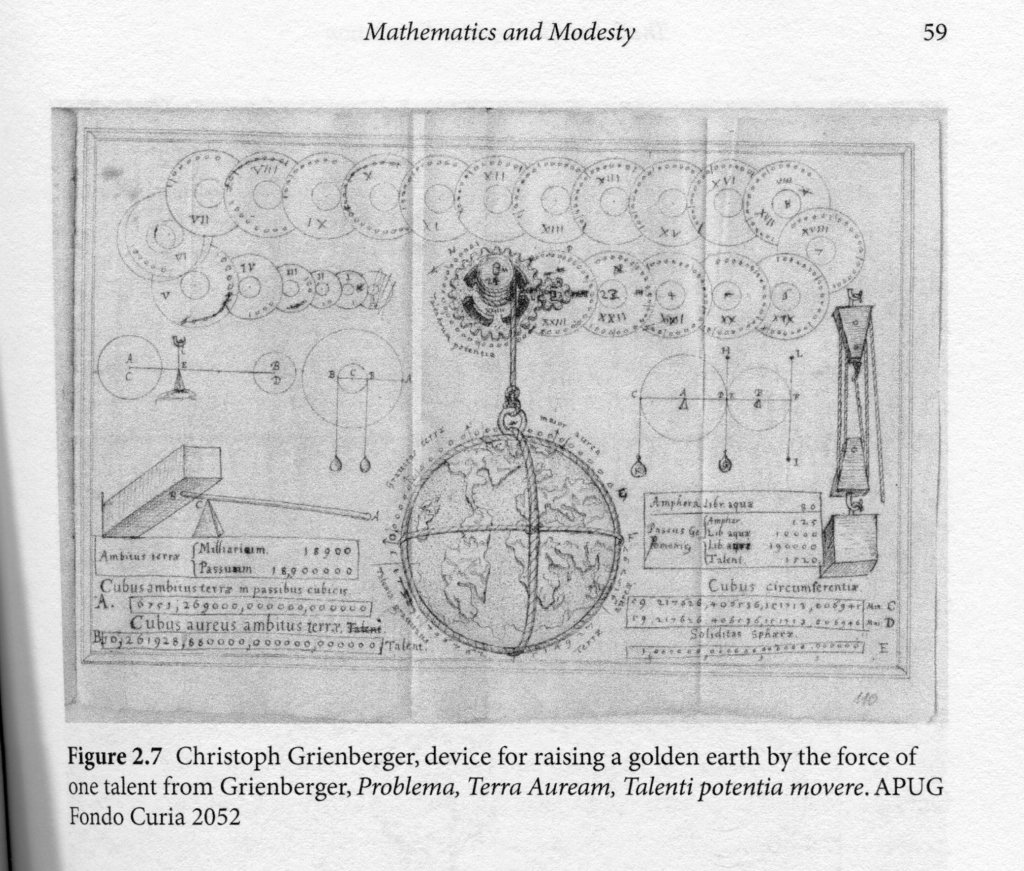

The second chapter, Mathematics and Modesty: The Problemata of Christoph Grienberger, illustrates the Jesuits personal requirement of humility and rejection of vanity in their work. This is illustrated with a description of the life and work of Christoph Grienberger, Clavius’ successor as professor for mathematics at the Collegio Romano, who almost completely disappeared behind his work. Perhaps the most extreme example of the abrogation of personality.

The Jesuits provide a difficult subject for the historian of the scientific revolution because they are not the enemies of science that some try to paint them nor are they, despite their own substantial contributions, unrestricted supporters of the new developments in science. There is a tension between the Clavian application of modern mathematics and experimentation to the sciences and the fundamental Jesuit obligation to adhere to the Aristotelian science of Thomist philosophy. Gorman’s book expertly brings this paradox out into the open displaying and analysing it from all sides.

The third chapter of the book, Discipline, Authority and Jesuit Censorship: From the Galileo Trial to the Ordinatio Pro Studiis Superioribus, is an in-depth analysis of this paradox. Gorman actually argues, convincingly, that the Jesuits’ requirement that all scientific texts be submitted to the authorities for censorship is an early form of peer review.

The fourth chapter, The Jesuits and the Vacuum Debate, was the one that I found most fascinating and from which I learnt the most. The invention of the Torricellian Tube, or barometer, unleashed a heated debate in the seventeenth century as to whether the empty space at the top of the tube was or was not a vacuum. Aristotle had argued that a vacuum could not exist, so the Jesuits were forced to take the side of denial, as we now know the wrong side. As is often the case in the history of science, their opposition actually stimulated the advancement of the science, as the supporters of the vacuum theory were required to counter their arguments. Interestingly the Jesuit opposition was not just philosophical. One of the principal supporters of the vacuum theory was another, non-Jesuit, Catholic scholar, and the Jesuits feared that if he won the debate that this would lead to a diminishing of their dominance in Catholic education. The whole chapter is an excellent example of the complexity of scientific evolution and its history.

There now follow two chapters on Athanasius Kircher, perhaps the most well-known scientific, Jesuit scholar of the century. The first, The Angel and the Compass: Athanasius Kircher’s Geographical Project, deals with Kircher’s failed project to create a new, reformed geography of the entire world by creating a world spanning network of researchers providing input to a central authority, himself. Although Kircher’s project, inspired by similar smaller collective research projects of Peiresc and Mersenne, in the end failed, Gorman sees the attempt as an important step in the evolving practice of scientific research. He also sees the Jesuits process of the central accumulation of scientific data in the Collegio Romano via world-wide correspondence, as an important model for others working in science.

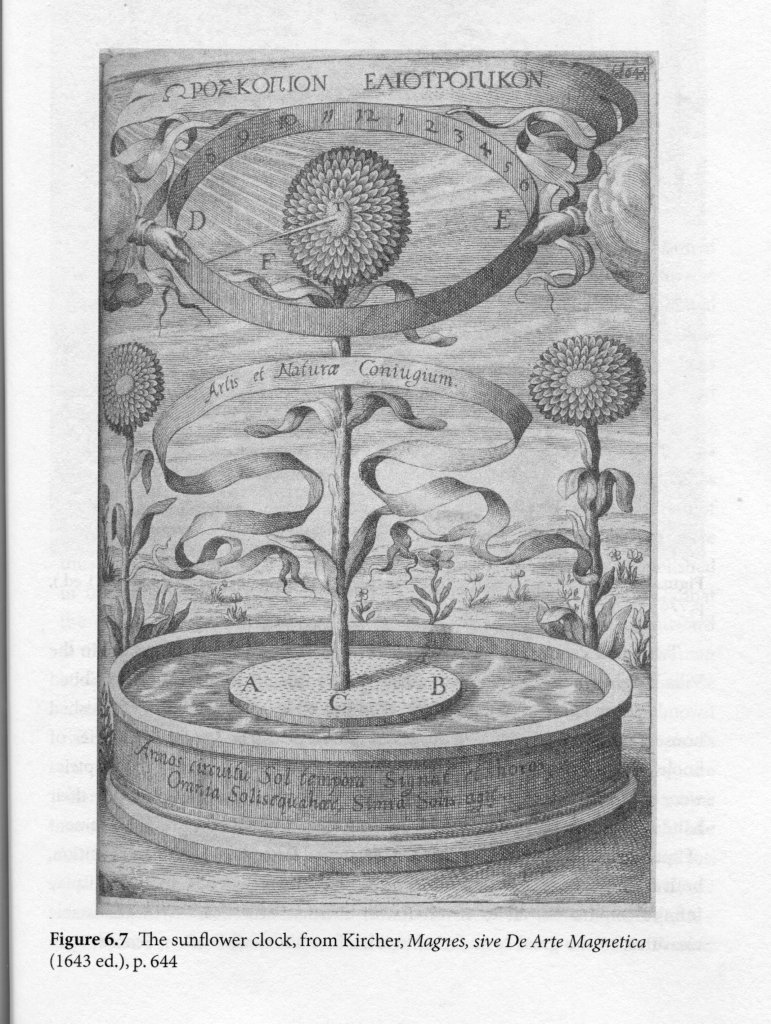

The second chapter on Kircher, Between the Domonic and the Miraculous: Athanasius Kircher and the Baroque Culture of Machines, takes a detailed look at Musaeum Kircherianum and its role as a public magnet to promote the Jesuit Order under the European civil and scientific aristocracies. He details the explanations of natural magic given by Kircher and above all his disciple Kasper Schott to explain the function of Kircher’s automatons, machines that initially appear to contradict the laws of nature but whose secret can be explained by those same laws.

Gorman’s final chapter, From ‘The Eyes Of All’ to ‘Usefull Quarries in Philosophy and Good Literature’: The Changing Reputation of the Jesuit Mathematicus, re-examines the trajectory of his book from Clavius to Kircher and how the emphasis and public presentation of the mathematicians of the Collegio Romano had changed over the century, not necessarily for the better.

Gorman is an excellent writer and his prose is clear and a pleasure to red. The book is illustrated with a series of greyscale illustration. There are informative endnotes, no footnotes, at the end of each essay but unfortunately no general bibliography. There is a good index.

At the end of the introduction, we can read:

A visit to the publisher’s website reveals the following

The site you are trying to reach has now been archived. Please contact [email protected] for access.

Apart from this irritation, the book is, as already stated, excellent and definitely a must read for anybody interested in the Jesuits’ contribution to the evolution of science in the seventeenth century.

[1] Michael John Gorman, The Scientific Counter-Revolution: The Jesuits and the Invention of Modern Science, Bloomsbury Academic, London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney, 2020, ppb. 2022