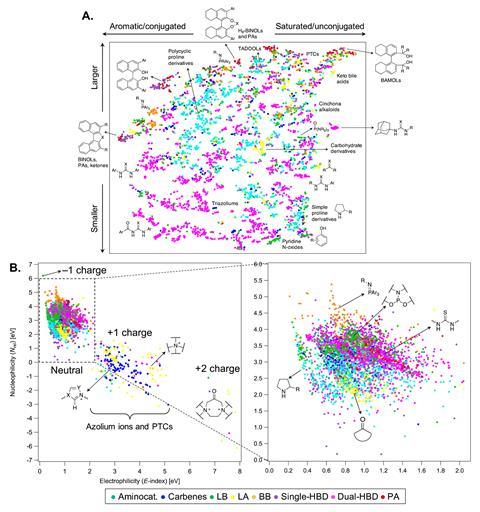

Researchers have constructed a public database of 4000 experimentally derived organocatalysts. The database also contains several thousand molecular fragments and combinatorially enriched structures based on the experimentally derived entries. It ‘represents the first steps towards an extensive mapping of organocatalyst space with large chemical diversity,’ says database co-creator Clémence Corminboeuf from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL). Researchers will be able to use the Organic structures for catalysis repository database, known as Oscar, ‘to train machine learning models and predict the properties of new catalysts’ comments EPFL team member Simone Gallarati. The team also hope the database will function as a starting point for organic chemists designing new catalysts.

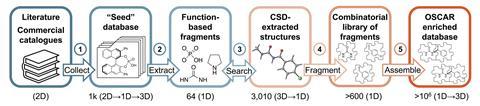

During the curation of Oscar, the Corminboeuf group developed a general strategy to collect, fragment and reassemble structures to generate thousands of new compounds. This fragment-based approach combines different motifs from existing catalysts with different linkers to build up a large set of structures that may not have been studied experimentally before. Robert Paton, from Colorado State University, US, and a member of the Centre for Computer Assisted Synthesis, says that ‘the ability to predict or survey structures that haven’t actually been synthesised yet is going to be very exciting’.

Recent years have seen a movement towards open science and data sharing. While some researchers are fearful about being scooped, most see the benefits, including insights based on old and new data, cross-validation and transparency. Creating extensive, customised databases is essential for developing data-driven tools in catalysis and other chemical fields. So, in an effort to improve data sharing across catalytic chemistry, the curators of Oscar have made the catalysts’ structures and properties publicly available on Materials Cloud. ‘The whole field is going to be accelerated by access to high quality data and I think that’s what this team has done,’ says Paton.

With Oscar now giving access to organocatalysts’ building blocks, Corminboeuf says they ‘plan to use them together with molecular generative models, specifically genetic algorithms, to discover new molecules with desirable target properties’. ‘During these evolutionary experiments, we can find the best combinations of fragments that yield better, more efficient organocatalysts,’ she adds.

The EPFL team suggest that their database will not only help establish data-driven reaction optimisation methods in organic synthesis, but the general strategy used to curate it will assist those building previously unavailable databases.