### Galileo vs. The Church: A New Look at the Historical “Affair”

The internet has reignited discussions surrounding Galileo Galilei’s confrontation with the Catholic Church, leading to a variety of debates regarding historical viewpoints, the involved science, and the larger consequences of the infamous “Galileo Affair.” Much of this revived focus may be attributed to a mixture of event misrepresentations, myth-making, and a propensity to simplify what was actually a complex incident encompassing science, theology, politics, and personal rivalries during the early 17th century. Although the narrative is frequently portrayed as a simple dichotomy between science and religion, the truth is considerably more intricate.

Let us explore the facts further and address some of the inaccuracies circulating in these online discussions.

—

### **The Fallacy of Heliocentric “Evidence”**

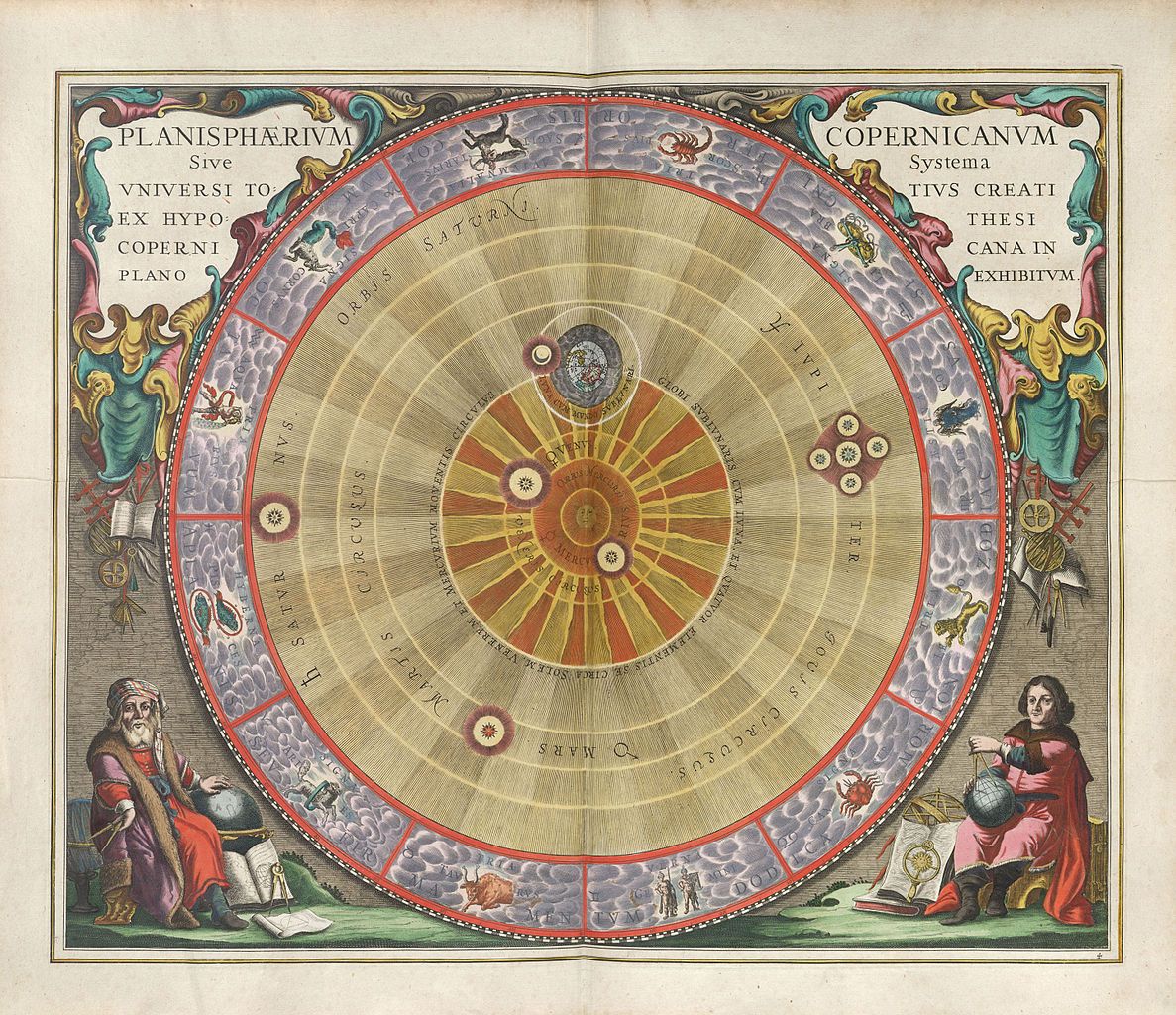

A common assertion is that Galileo had unequivocal evidence for heliocentrism—the concept that the Sun occupies the center of the universe and that the Earth revolves around it. In truth, Galileo lacked conclusive empirical data to substantiate the Copernican model.

Central to this is the misconception regarding the phases of Venus, which Galileo noted through a telescope. Although Galileo’s observation of the phases of Venus indicated that Venus orbits the Sun, this finding was compatible with multiple cosmological models beyond the Copernican heliocentric framework—particularly the Tychonic (geo-heliocentric) and Capellan systems. The Tychonic model, introduced by Tycho Brahe, posited that planets revolved around the Sun, which in turn revolved around a stationary Earth. This model, while fundamentally geocentric, adeptly explained the phases of Venus and the observations available at the time.

In summary, Galileo’s telescope findings lent support to a Sun-centered solar system but did not serve as definitive proof. Considering the astronomical knowledge available in the early 17th century, Galileo’s adherence to Copernican heliocentrism was more an act of philosophical belief than one based on undeniable scientific proof.

—

### **The Church’s Doctrinal Concerns**

The Galileo Affair can only be comprehensively understood within the historical and theological context of the Counter-Reformation. During this era, the Catholic Church was heavily invested in countering the challenges presented by Protestant reformers and reinforcing its authority—especially its dominance in the interpretation of scripture. This struggle for interpretive supremacy was crucial to the conflict between Galileo and the Church.

Both Galileo’s *Letter to Castelli* and the correspondence from Carmelite priest Paolo Antonio Foscarini to Cardinal Bellarmine contained calls for a reinterpretation of specific biblical verses that seemingly endorsed a geocentric perspective of the universe (e.g., Joshua 10:13, where the Sun and Moon are depicted as standing still). For the Church, these challenges transcended mere astronomy; they were about questioning the Church’s authority to interpret biblical texts. Galileo—a layperson and mathematician—was perceived as overstepping his role by insisting on theological arguments.

The Church’s 1616 prohibition against Galileo came after an assessment of heliocentric propositions by a group of theologians termed qualifiers. Their conclusion was that the notion of a stationary Sun and a moving Earth was “foolish and absurd in philosophy” (i.e., inconsistent with the empirical evidence of that era) and “formally heretical” since it contradicted scripture. Importantly, however, heliocentrism was never officially declared heretical by the Church as an institution, a crucial distinction frequently overlooked in popular narratives.

—

### **Galileo’s Trial: The Actual Events**

In 1632, Galileo published his *Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems*, which ostensibly presented both the Ptolemaic (geocentric) and Copernican (heliocentric) models on equal footing. However, the *Dialogue* was essentially a sophisticated political argument and subtly veiled support for the Copernican paradigm. Galileo deftly used his considerable rhetorical abilities to dismantle the Ptolemaic perspective, portraying the model’s defender—a character known as “Simplicio”—as foolish and inept. Adding to the tension, Pope Urban VIII, a previous supporter of Galileo, felt personally insulted by the arguments attributed to Simplicio. This personal animosity certainly escalated the gravity of Galileo’s trial.

Galileo was called to Rome, where he resided in relatively comfortable conditions during the trial. He eventually confessed to “vehement suspicion of heresy” and received a life sentence, which was soon converted to house arrest. Consequently, Galileo spent his later years at his villa near Florence, where he continued his scientific pursuits, including the writing of his *Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences*.