### Grasping “Behavioural Fatigue” and Its Significance for Public Health During a Pandemic

The term “behavioural fatigue” received significant attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially as it was used by the UK Government to rationalize the postponement of stricter public health interventions. Originally presented as a cause for concern, this notion was subsequently contested, with critics asserting that it lacked a foundation in scientific evidence. A 2020 piece in *The Guardian* contended that the idea itself was flawed and unsupported by data. Nevertheless, this dismissal warrants thorough examination, as there is considerable academic research investigating how human behaviour shifts during epidemics and pandemics. While the observed phenomenon of decreasing compliance may not precisely fit the definition of “behavioural fatigue,” it is undoubtedly a topic worth examining.

As we work together to adopt and uphold public health practices, comprehending the complexities of human behaviour during health emergencies can benefit policymakers and individuals alike. This article surveys the pertinent research, addresses misunderstandings, and provides insights into what drives ongoing behavioural adherence—or its decline.

—

### The Emergence of “Behavioural Fatigue” and Its Misapprehension in Scientific Communication

The expression “behavioural fatigue” seems to have gained traction in societal conversations during COVID-19, yet it does not distinctly appear in medical or epidemiological texts. Instead, the term probably functioned as an engaging metaphor to encapsulate worries about decreasing adherence to behavioural strategies such as social distancing or wearing masks. Numerous public health specialists quickly noted that the term was inadequately defined and that the issues it sought to address—people’s diminishing commitment to public health guidelines over time—were already being explored through alternate frameworks.

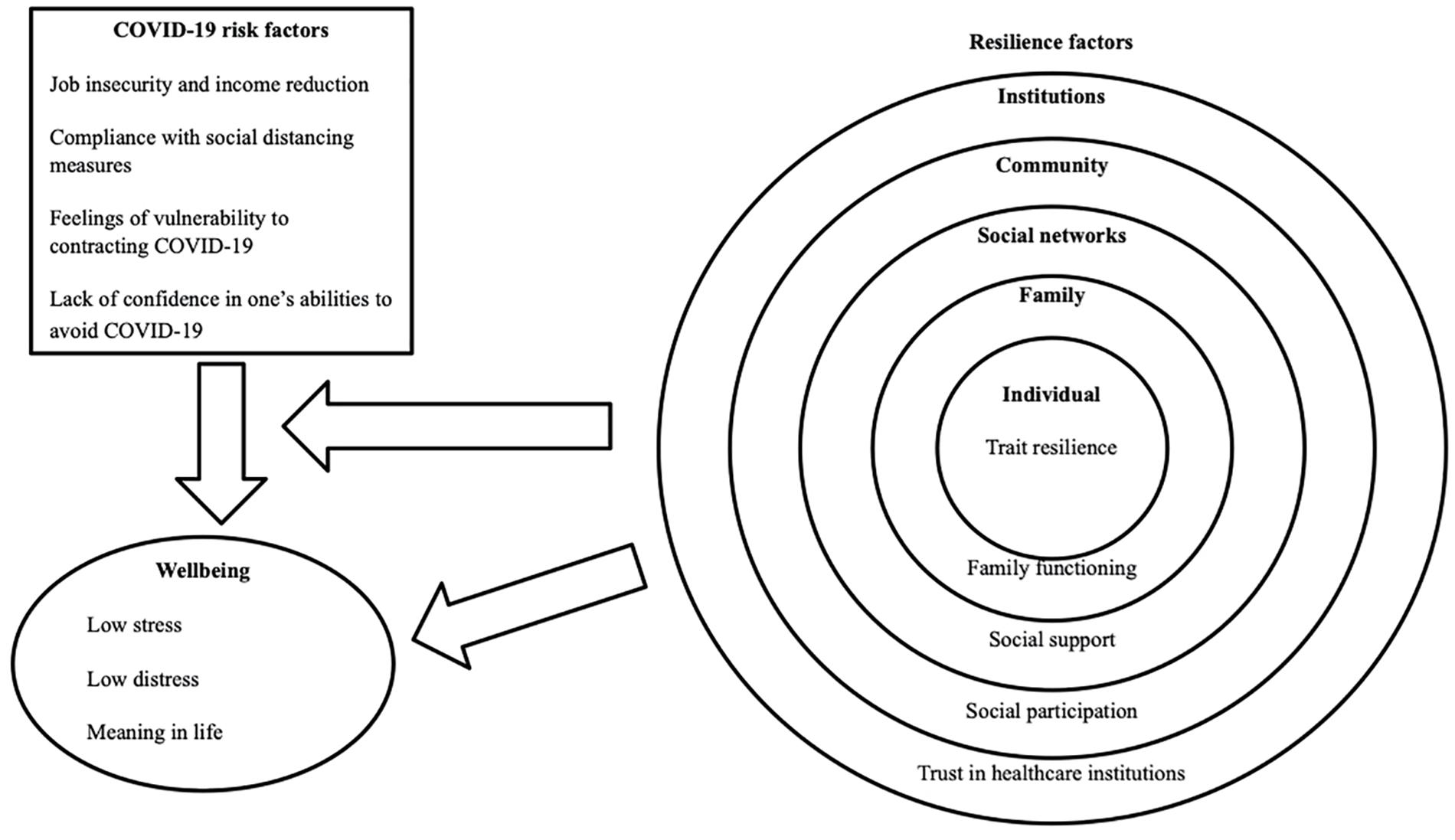

For instance, psychologists and epidemiologists have investigated how alterations in *risk perception* impact adherence to protective actions. Qualitative research has also looked into how conflicting obligations, such as caregiving duties or financial strains, lead to changes in behaviour over time. While these studies might not explicitly utilize the term “behavioural fatigue,” they provide evidence of fluctuating compliance during health emergencies.

—

### Insights from Epidemics and Pandemics: Behavioural Trends Over Time

The human response to epidemics has been comprehensively explored in various instances, including the 2006 avian influenza outbreak, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, and the 1918 influenza pandemic. These investigations have demonstrated how adherence to preventative practices tends to evolve, shaped by factors such as perceived danger, emotional reactions, socioeconomic challenges, and cultural norms.

#### 1. **Shifts in Risk Perception**

A crucial insight in behavioural science is that individuals’ understanding of risk frequently diverges from actual threats. A significant model, first proposed in the 1990s, outlines how risk perception transforms during an epidemic. At the outset, when dangers are high yet unfamiliar, individuals often overestimate risk and enhance compliance. However, as they adapt to the new situation—even when actual risks escalate—their perception of risk diminishes. This adjustment can occasionally foster complacency regarding public health practices.

#### 2. **Declining Compliance Evidence**

A range of studies from previous epidemics has documented a drop in adherence to preventative behaviours over time. For example:

– During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, research in Hong Kong and Malaysia observed decreases in behaviours such as handwashing and social distancing as the outbreak progressed, even while adherence to other measures remained steady.

– In Italy, self-reported metrics indicated a reduction in commitment to specific measures as the urgency initially felt decreased.

– A 2006 study conducted in the Netherlands noted a pattern of fluctuating adherence during the avian influenza outbreak, where initial compliance rose, declined, and then saw a resurgence.

Objective behavioural measures also corroborated these trends. For instance, a study during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Mexico used television viewing as an indicator of time spent at home. It identified an increase in viewing at the pandemic’s outset, signifying adherence to social distancing, but this declined as the epidemic advanced.

#### 3. **Stability and Resilience**

Notably, not all research indicated a decrease in compliance. In some scenarios, individuals maintained or even heightened their commitment to health practices over time:

– A study in the Netherlands during the chikungunya outbreak (a mosquito-borne illness) demonstrated a consistent rise in preventative behaviours among participants.

– Another investigation in Beijing during the H1N1 outbreak found that individuals sustained compliance with low-effort actions (e.g., handwashing, proper coughing etiquette) while intensifying higher-effort measures (e.g., stockpiling supplies, purchasing masks).

These outcomes suggest that while behavioural decline may happen in certain instances, it is neither an unavoidable nor widespread phenomenon.

—

### The Role of Modelling in Comprehending Epidemics

In addition to observational studies, mathematical models have shed light on how behavioural dynamics interact with disease progression. A notable trend is that numerous epidemics occur in waves—