# Book Review: *Before You Know It* by John Bargh – A Critical Analysis

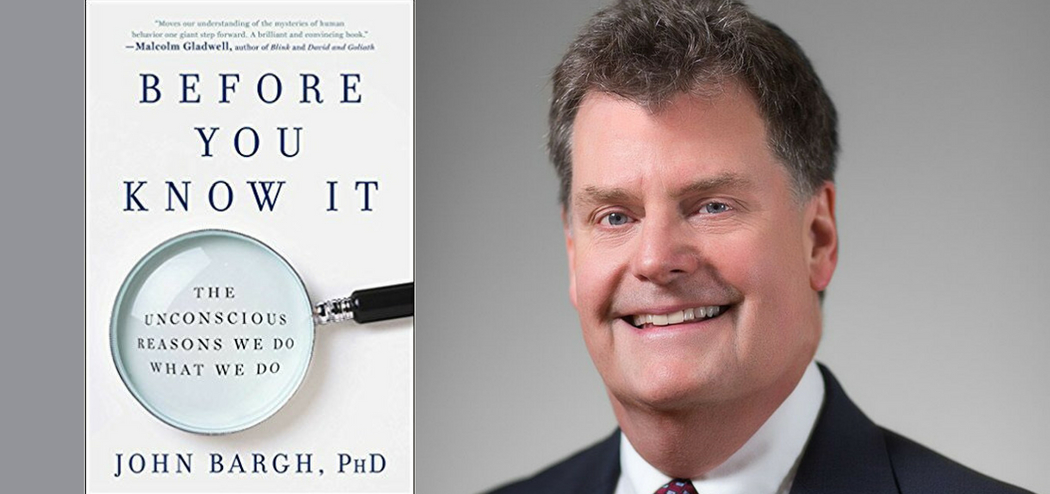

John Bargh, a prominent figure in social psychology, is well-known for his innovative studies on the unconscious mind. His work, *Before You Know It: The Unconscious Reasons We Do What We Do*, seeks to thoroughly explore the ways in which unconscious mechanisms influence human behavior. Nevertheless, although the book boasts an engaging storyline filled with fascinating experiments and stories, it falls short of tackling significant criticisms, especially considering the recent replication crisis in psychology.

## The Strengths: Engaging Narrative & Thought-Provoking Experiments

Bargh skillfully intertwines real-life instances, personal stories, and psychological studies to demonstrate the intricacies of unconscious effects on behavior. His passion for the topic radiates through captivating accounts of human motivation, habits, and the impact of the environment.

A notable strength of the book is its discussion of “social priming”—the concept that minor cues in our surroundings can unconsciously influence our behavior. One well-known experiment illustrates this idea: participants subjected to terms associated with old age were later observed walking at a slower pace. Furthermore, another research study mentioned indicates that holding a hot beverage can lead individuals to view others as more “emotionally warm.” These findings imply that our unconscious mind steers our actions in ways that often elude our awareness.

Moreover, Bargh incorporates perspectives from diverse psychological theories, referencing figures like Freud, Skinner, and Darwin. He does not isolate social psychology but instead frames it within a larger, multidisciplinary context of human cognition and behavior. This extensive historical and theoretical foundation is among the book’s assets.

## The Shortcomings: The Replication Crisis & Conceptual Issues

Despite its engaging narrative, *Before You Know It* has considerable shortcomings, particularly in light of current discussions in psychology. Many well-known studies referenced in Bargh’s work—including his own social priming research—have been critically examined or shown failure to replicate due to the psychology’s “replication crisis.” The book notably neglects to confront these critiques, an important lapse given Bargh’s influential role in this research area. The lack of discussion about replication failures, which have raised concerns over the dependability of social priming effects, considerably undermines the book’s authority.

Additionally, Bargh’s use of the term “unconscious” is broad and at times ambiguous. The term often seems to encompass any behavior that individuals do not explicitly articulate or fully clarify. This interpretation is overly general and presents theoretical challenges. In experimental contexts, a participant’s inability to pinpoint how a particular factor influences them does not indicate they were “unconscious” of it in any impactful sense. If “unconscious” merely equates to “not openly discussed,” then it strips the term of its more profound conceptual value.

## Missed Opportunities for Depth & Critical Discussion

While *Before You Know It* delivers an enjoyable and approachable overview of psychological research, it overlooks the chance for greater depth in scientific examination and personal storytelling. The book addresses social priming experiments and their significance but frequently fails to delve into alternative interpretations, conflicting results, or practical applications thoroughly.

In a similar vein, although Bargh shares snippets of his personal and professional journey, they often come off as lacking or underdeveloped. For instance, he briefly recounts a serendipitous meeting in a diner that led to his marriage, yet provides scant details about his spouse or their relationship. Expanded personal narratives could have enriched the overall story.

## Final Verdict

*Before You Know It* serves as a stimulating and insightful read that exposes readers to the unconscious forces influencing human actions. However, its neglect to engage with the replication crisis and its overly expansive interpretation of the unconscious undermine its scientific credibility. For readers seeking an enjoyable introduction to social psychology, the book provides both valuable information and entertainment. Conversely, for those wanting a deeper engagement with ongoing psychological debates, its lack of critical reflection may prove to be disappointing.

Overall, Bargh’s work is a captivating read, yet it ultimately leaves numerous vital questions unaddressed.