Understanding Science in Context: The Significance of Historical Narrative

In contemporary historical narratives, science is frequently depicted as a linear journey of advancement—each significant idea seamlessly leading to the next, creating a tidy chronology of discoveries that reflects modern comprehension. However, this view is fundamentally flawed for narrative historians of science like myself. As a contextual historian, my aim is to reintegrate science into the temporal and cultural settings where it first arose, to uncover how science genuinely progressed—in the complex, contingent, and richly contextual human landscape.

Rather than being developed in isolation, science emerges from interconnected histories: of geography, political landscapes, economic systems, and belief frameworks. Only through grasping these contexts can we genuinely comprehend science as a human endeavor. Indeed, it is solely by situating ideas within their temporal and cultural environments that we can recognize the significance of science and understand how it evolved through the contributions of the people who shaped it.

The Risks of Presentism

This viewpoint directly counters a prevalent error in the historiography of science referred to as presentism: evaluating or interpreting the past based on contemporary knowledge or values. Presentism extracts elements of science from their historical contexts simply because they bear resemblance to modern scientific ideas. For instance, showcasing an ancient equation that appears similar to Newton’s laws does not imply that earlier civilizations “foresaw” Newton; it overlooks how differently ancient people conceptualized the world prior to the formalization of ideas such as motion, force, and gravity.

Presentism simplifies historical complexity, transforming the richly contextual evolution of knowledge into anachronistic stepping stones along an imagined route to progress. It conceals more than it illuminates.

Astrology and Astronomy: A Unified Discipline in Context

A revealing illustration of how context alters our understanding is astrology—frequently dismissed today as pseudoscience, a remnant of ignorance. Yet, historically, astrology was not merely tolerated; it served as a significant framework in the development of modern astronomy.

Throughout antiquity and well into the early modern era, astrology and astronomy were perceived as two facets of a singular discipline. Claudius Ptolemaeus (Ptolemy), arguably the most prominent astronomical thinker of antiquity, authored both the Almagest (astronomy) and the Tetrabiblos (astrology), perceiving no essential division between the two. The observation of celestial bodies for astrological charting necessitated precise positional tracking of stars and planets, and the demands of astrology spurred advancements in astronomical methodologies.

By dismissing astrology as “nonsense,” many previous historians of science overlooked the rich, productive interplay between what we now categorize as distinct fields. Yet, when viewed through a contextual lens, astrology is not merely superstition; it acts as a significant catalyst for astronomical progress, intricately woven into its social, religious, and political contexts.

Mathematical Sciences and Trade in Renaissance Nürnberg

A closer historical example of contextual development can be seen in Renaissance Nürnberg. This city emerged as a center for mathematical sciences, not due to academic enlightenment or scholarly breakthroughs, but as a result of trade and local economic conditions.

Nürnberg’s ascendance in scientific instrumentation and mathematical proficiency was grounded in its status as a commercial hub. Merchants, engineers, artisans, and mapmakers had practical necessities: to navigate, construct, and manage resources with increasing accuracy. This economic activity fostered a network of instrument makers and technical experts, subsequently igniting mathematical innovations. Here, science did not emerge from abstract theorizing—it was cultivated by commerce and the requirements of daily urban existence.

Mesopotamia: Between Two Rivers and Diverse Cultures

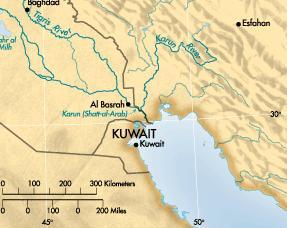

One of the most fertile grounds for understanding the contextual evolution of science and knowledge is ancient Mesopotamia—a region that encompasses present-day Iraq and parts of Syria, Turkey, and Iran. Often referred to as the “Cradle of Civilization,” this Eurocentric label fails to recognize equally ancient developments in the Indus Valley and China. What connects these early societies, however, is their emergence alongside major river systems—natural channels for agriculture, transport, and trade. In the case of Mesopotamia, this refers to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

It was in this area that writing originated—a foundational technology essential not just for administrative and legal systems, but also as a prerequisite for documenting scientific and astronomical data. The advent of clay tablets permitted the preservation of vast amounts of information, providing us with an extraordinary archive into early cognitive frameworks.

The cultures of this region—Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian—spanned millennia and yielded achievements such as:

– The creation of a base-60 numbering system

– The establishment of organized systems for astrology and astronomy

– Early forms of algebra and geometry

– Manuals for medical diagnosis based on symptoms and empirical observations

These traditions would shape subsequent developments in Greek science and Arabic scholarship. Understanding them within context necessitates an exploration of cultural, political, and religious structures—how temples acted as centers of knowledge or how scribes were trained to interpret omens and document astronomical occurrences.