Brown Rice vs. White Rice: Nutrition, Arsenic, and the Balance Between Health and Safety

When navigating the grocery store or selecting your dish at a restaurant, you’ve probably pondered whether to choose brown rice over white rice. Brown rice has been praised as the healthier option due to its greater fiber content, vitamins, and complex carbs. However, recent studies indicate that there are additional factors to weigh beyond just nutritional value — particularly, the food safety issues regarding arsenic levels.

New research from Michigan State University, published in the journal Risk Analysis, has reignited focus on the arsenic levels in rice, particularly brown rice. This new understanding could complicate our health-related choices.

Grasping Arsenic in Rice

Arsenic, a naturally present element in the earth’s crust, is recognized as a toxic substance that can accumulate within the human body over time. High levels of arsenic exposure are linked to multiple health issues — such as certain types of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodevelopmental challenges in children.

Rice distinguishes itself from other grains concerning arsenic absorption. Due to its growing conditions — usually in flooded paddies — rice plants absorb significantly more arsenic from the environment than other crops. In fact, rice can absorb up to 10 times more arsenic compared to other cereals.

Brown rice, which retains its outer bran and germ layers, harbors greater amounts of these harmful substances. Conversely, white rice has had these layers removed, which leads to lower overall arsenic levels.

Notable Research Insights

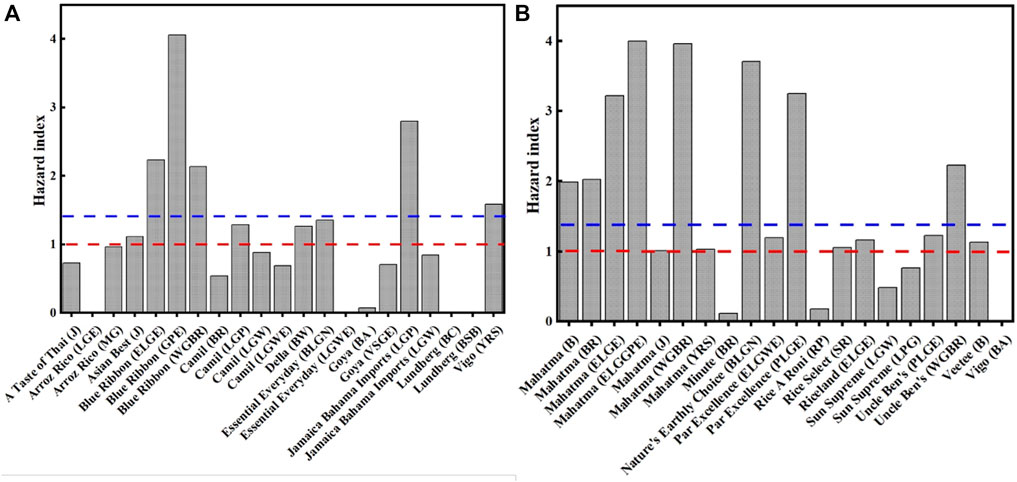

Headed by senior researcher Dr. Felicia Wu and postdoctoral associate Dr. Christian Scott at Michigan State University’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, the latest study evaluated arsenic exposure risks in brown versus white rice among U.S. populations. By examining dietary data from the “What We Eat in America” database and other federal resources, the researchers analyzed average rice consumption patterns based on demographics, age, and region.

Key findings from the study include:

– On average, brown rice has higher levels of both total and inorganic arsenic than white rice.

– The inorganic arsenic, which is the most harmful to health, constituted 48% of total arsenic in domestically grown brown rice, compared to 33% in white rice.

– For rice sourced globally, that percentage rose: 65% of total arsenic in brown rice was inorganic, versus 53% in white rice.

– Infants and young children (especially those under five) may be at greater risk due to their high food-to-bodyweight ratio.

– Certain groups, like Asian immigrant communities and individuals experiencing food insecurity, face increased exposure due to higher rice consumption.

While the average American adult likely won’t face severe health risks from occasional brown rice consumption, the long-term effects on vulnerable groups, particularly children, are a significant concern.

The Brown vs. White Discussion: Beyond Nutrition

Dr. Wu advocates for caution rather than panic. “Even though arsenic levels are slightly elevated in brown rice compared to white rice, further research is essential to establish whether the possible risks from this exposure outweigh the nutritional advantages offered by the rice bran,” she remarked.

Brown rice provides considerable dietary benefits: it boasts more fiber, greater protein content, and crucial nutrients like magnesium and niacin. However, when choosing what to eat, it’s crucial to acknowledge that health considerations are complex.

Thus, the inquiry shifts from merely selecting the most nutritious option to choosing the safest one — especially for children and at-risk groups.

Geographical and Global Insights

Interestingly, the origin of your rice plays a crucial role. The study indicated variations in arsenic levels according to the rice’s geographic source.

– Rice cultivated in the U.S. generally exhibited lower inorganic arsenic levels compared to rice from Asia and other worldwide regions.

– Areas and communities with significant rice cultivation or high consumption may require more robust mitigation strategies and public health measures.

Policy Developments and Public Awareness

This research has sparked significant policy discussions, particularly in regard to regulatory initiatives like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s “Closer to Zero” campaign, aimed at decreasing exposure to harmful elements in foods consumed by infants and young children.

While arsenic levels in water are already regulated, rice — a prevalent weaning food for babies — has not undergone similar stringent oversight. Establishing action levels for arsenic in rice products could be a forthcoming step that informs policy guidelines and consumer practices.

The Conclusion for Consumers

So, should brown rice be avoided? Not necessarily. Recognizing the entire situation enables you to make more informed choices.

Here are some consumer suggestions:

– Variety in grain selection: Incorporate a range of whole grains in your diet, such as quinoa, barley, or farro, which generally have much lower arsenic levels.

– Diversify your carbohydrate sources: Alternate between various carbohydrates like potatoes, legumes, and pasta to minimize overall arsenic exposure.

– Soak