Title: Study Reveals High-Fat, Low-Fiber Diets Hinder Gut Microbiome Recovery After Antibiotics

Research conducted at the University of Chicago and published in Nature indicates that high-fat, low-fiber diets—often known as Western-style diets—can significantly obstruct the gut microbiome’s recovery following antibiotic usage. The study implies that modifying one’s diet, rather than relying on fecal microbiota transplants (FMT), could be the most effective approach for restoring gut health after antibiotic treatments.

Antibiotics and Gut Microbiome Well-Being

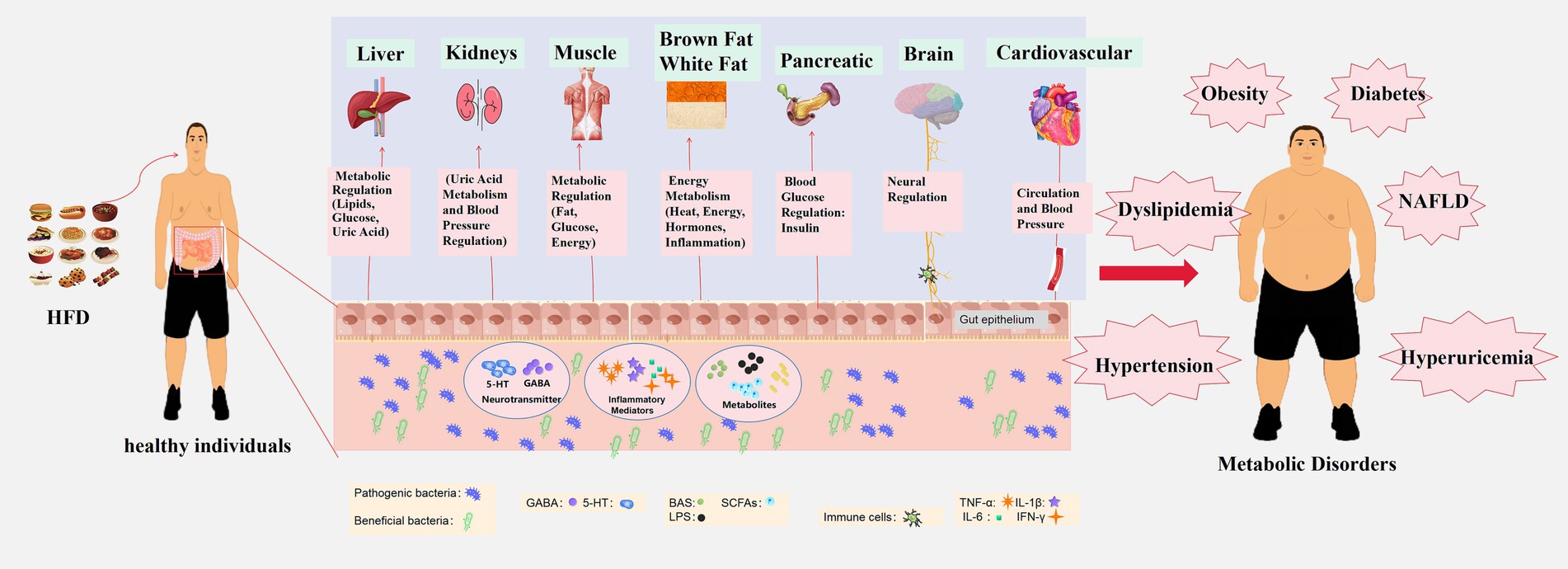

The gut microbiome comprises trillions of microorganisms that play vital roles in digestion, immune defenses, and protection against harmful invaders. While antibiotics are crucial for combating bacterial infections, they also indiscriminately destroy many beneficial gut microbes. This depletion can expose individuals to infections, metabolic issues, and inflammatory conditions.

Researchers from the University of Chicago, led by Dr. Eugene B. Chang, a medicine professor, investigated how diet influences the recovery process post-antibiotics. They administered antibiotics to two groups of mice; one group was given a standard, fiber-rich diet, while the other was placed on a Western-style diet characterized by high fat and low fiber.

The outcomes were striking. Mice on the fiber-rich “chow” diet restored a diverse, functional microbiome within a matter of days. In contrast, those on the Western diet suffered a prolonged collapse of their microbiome that lasted for over nine weeks. This hindered recovery made them vulnerable to pathogens like Salmonella—an organism that usually cannot establish itself in a gut with a healthy microbiome.

The Importance of Dietary Fiber

Central to the recovery process is the idea of microbial succession—a gradual reestablishment of microbial diversity after disruption. Foods rich in fiber support this process by promoting cross-feeding among various bacterial species. Microbes consume plant fibers and produce byproducts, including short-chain fatty acids, which nourish other beneficial bacteria. This interconnected system of microbial support aids in rebuilding a stable and resilient microbiome.

Conversely, the Western diet promotes dominance by a limited number of microbial species that monopolize nutrients, creating a monoculture-like setting that inhibits broader ecological stability. Lead author Megan Kennedy, a student in the Medical Scientist Training Program at UChicago, noted, “We were genuinely surprised by the stark contrast in recovery processes between mice on the Western-style diet and those on the healthier one.”

Ineffectiveness of Fecal Microbiota Transplants in Poor Diets

A particularly surprising result from the study was that FMT—a procedure transferring healthy bacteria from a donor into a patient’s gut—proved ineffective in mice on a Western diet. Even well-matched transplants did not succeed in revitalizing a diverse microbial community.

“It seems irrelevant what microbes you introduce to the community through FMT, even with the perfect match for an ideal transplant,” stated Kennedy. “If the mice are on an unsuitable diet, the microbes fail to adhere, the community doesn’t diversify, and recovery is not achieved.”

This underscores the crucial role of diet in shaping the microbial landscape. Without appropriate dietary inputs—especially fermentable plant fibers—even the most sophisticated microbial therapies could be ineffective.

Nutrition as Therapy

Dr. Chang compares antibiotic treatment to a forest fire devastating a complex ecosystem. “The mammalian gut microbiome resembles a forest, and when it is damaged, a specific sequence of events is required for it to restore itself to its previous health,” he elaborated. “On a Western diet, this restoration process does not occur because it lacks the necessary nutrients at the right times for the appropriate microbes to recover.”

This research marks a pivotal change in how scientists and healthcare providers might approach microbiome restoration. Rather than relying solely on probiotics or microbial transplants, dietary modifications provide a more comprehensive and sustainable method for rebuilding gut health. Chang emphasized: “I’ve become convinced that food can serve as medicine. In fact, I believe food can be prescriptive since we can ultimately determine which food components influence which populations and functions of the gut microbiome.”

Consequences for Human Health

These discoveries have significant implications, particularly for millions of Americans who regularly consume Western-style diets and use antibiotics. Patients recovering from infections, undergoing cancer therapies, or receiving organ transplants frequently require multiple courses of antibiotics. For these individuals, targeted dietary changes—rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains—might help restore microbial equilibrium, enhance immune response, and lower the risk of subsequent infections.

What You Can Do

Those expecting to undergo antibiotic treatment can potentially protect their gut microbiome by proactively adding more fiber-rich foods to their diet. Suggested items include:

– Leafy greens like spinach and kale

– Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and cauliflower

– Legumes like lentils, chickpeas, and black beans

– Whole grains,