In recent years, essential oils and herbs have garnered growing attention within popular culture, often heralded as possible solutions for various health issues. Although these assertions may spark curiosity, they typically rely on insufficient scientific evidence. An article from The Atlantic highlighting the potential of essential oils as emerging antibiotics has stimulated conversations, illuminating the varied uses of essential oils while also underscoring the need to comprehend what truly renders a molecule effective as a medication.

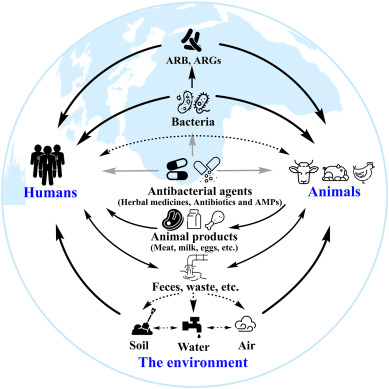

The article presents three key points regarding essential oils. First, it proposes that the addition of herbal essential oils such as oregano oil to livestock feed could enhance the health of farm animals, potentially reducing the reliance on antibiotics, which are known to hasten the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in humans. However, the feasibility of this approach remains ambiguous. Second, the article claims the effectiveness of tea tree oil as an antiseptic in hand sanitizers, which aligns with its current incorporation in numerous personal care items. Lastly, it posits that essential oils might be capable of treating infections in both humans and animals due to their bactericidal properties observed in petri dish studies. This final assertion, however, faces skepticism given the pharmaceutical sector’s indifference for financial reasons, despite calls for more thorough investigation.

Current consumer products already utilize compounds from essential oils such as thymol, sourced from oregano oil, which is frequently included in mouthwashes. Nonetheless, these applications are significantly distinct from pharmaceutical uses due to varying required characteristics. Here, a critical aspect of potential antibiotics emerges: the toxic dose must markedly differ from the effective dose for bacteria, in contrast to substances like salt or bleach, which are impractical due to the narrow margin between effective and toxic doses for humans.

To assess a compound’s antibiotic potential, two essential questions must be addressed: the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) required to cease bacterial proliferation, and the achievable blood concentration without triggering adverse effects. Regrettably, compounds such as thymol and carvacrol in oregano oil demonstrate high MICs, indicating weak antibiotic effectiveness that necessitates potentially harmful doses to maintain activity against bacteria.

Studies on thymol and carvacrol reveal their limited antibiotic effectiveness. Research, including those referenced in The Atlantic article, indicates their MICs are considerably higher than those of established antibiotics like vancomycin. Consequently, their use as antibiotics requires impractical blood concentrations, compounded by high clearance rates in the body, making their therapeutic application doubtful. Despite some promise as preservatives or antiseptics, their viability as antibiotics appears limited.

The broad enthusiasm for the antibacterial capabilities of essential oils likely arises from oversimplified interpretations of studies that lack contextual details. Media narratives may amplify claims by emphasizing the simple fact that essential oils can kill bacteria in vitro while neglecting crucial factors such as concentration and systemic toxicity. Furthermore, assertions regarding regulatory oversight are misleading, as all potential drugs must navigate comprehensive FDA approval processes to confirm safety and efficacy.

In summary, while essential oils and herbs exhibit potential in certain scenarios, their characterization as innovative antibiotics remains conjectural. A thorough understanding of pharmacological principles highlights significant obstacles in achieving therapeutic effectiveness without adverse impacts. Nevertheless, they persist in providing valuable contributions in non-medical applications.