Even prior to the establishment of psychology as a formal discipline, psychologists have been meticulously gauging reaction times, cementing this measurement technique as a long-standing element in cognitive psychology research. Reaction times are mainly employed to discern variations in cognitive processing by contrasting participants’ response times to stimuli across different conditions. Such variations in reaction times are interpreted to link with unique cognitive processing mechanisms.

Going back to the end of the 19th century, the pioneer of reaction time research, Francis Galton, an eminent individual renowned for his work in eugenics and statistics, collected an extensive dataset comprising 3,410 entries of ‘simple reaction times.’ Galton’s investigations deviated from the prevailing psychological trends, as he regarded reaction times as a metric for individual differences. He proposed that variances in cognitive processing speed might underlie differences in intelligence, suggesting that reaction times could act as a basic estimator for evaluating intelligence.

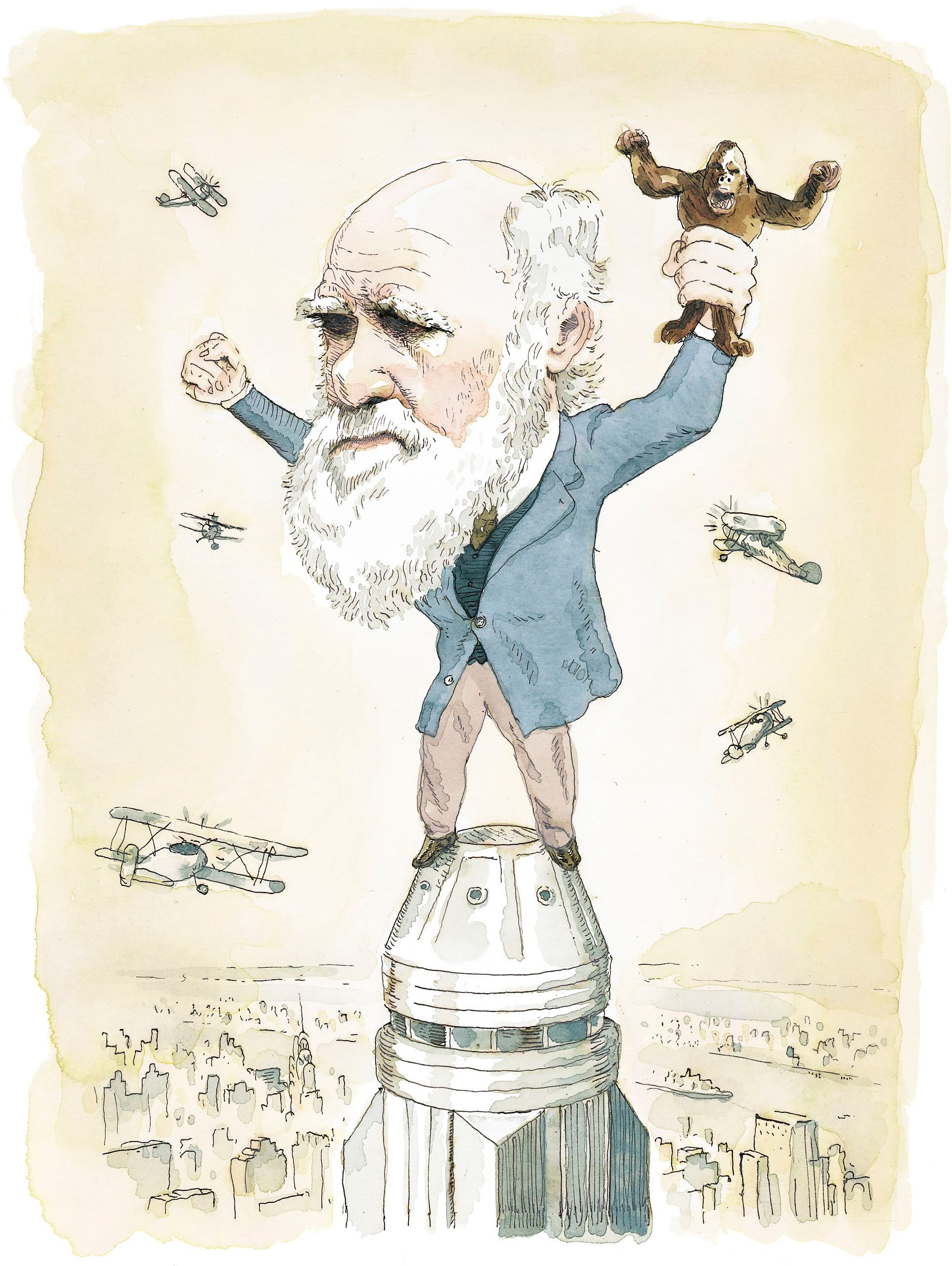

Fast forward over a century, an intriguing query emerges: do modern individuals exhibit faster or slower reaction times in comparison to Galton’s subjects? Should Galton’s hypothesis be valid, contemporary reaction time data could shed light on generational changes in cognitive functioning. This line of inquiry might not only hint at the probability of outpacing a Victorian gunslinger in a quick-draw challenge but also broaden our understanding of cognitive evolution over generations.

Reaction time data presents a fascinating counter narrative to the widely recognized generational increase in IQ scores, termed the Flynn Effect. The Flynn Effect astonishes those who instinctively perceive ‘kids today’ as less competent or those who theorize that more intelligent individuals have fewer children, anticipating a decline in intellectual capabilities in subsequent generations.

Contrasting the upward trend of IQ scores, reaction time data offers potential reassurance to those doubtful of cognitive deterioration. Numerous research analyses (1, 2) have sought to compare Galton’s results with those from modern studies, employing similar apparatus and methodologies. As pointed out by Silverman in 2010, almost all recent studies indicated longer reaction times when compared to Galton’s measurements, with differences unlikely attributable to timing device errors.

Reflect on the findings of Woodley et al. (2015), which demonstrate a secular slowdown of reaction times over a century across several studies conducted in the UK. This graphical representation indicates a slight ~20 milliseconds increase — roughly one-fiftieth of a second — suggesting that contemporary participants are approximately 10% slower in reaction times.

What conclusions can we draw from this? Typically, deductions would depend on a broader range of studies over time; nonetheless, revisiting participants from the 19th century for confirmation is impractical. The lack of intermediary studies hampers the ability to ascertain whether reaction time rates in the 1930s indeed fell neatly between Victorian and modern standards.

Even assuming the data’s accuracy, its implications are complex: does this signify a genuine cognitive decline, heightened cognitive demands on other functions, motivational shifts, or merely alterations in experimental methodologies or participant involvement? The data provokes more inquiries than definitive conclusions, leaving the verdict on the enduring capabilities of today’s youth pending.

References:

- Irwin, W. S. (2010). Simple reaction time: it is not what it used to be. American Journal of Psychology, 123(1), 39-50.

- Woodley, M. A., Te Nijenhuis, J., & Murphy, R. (2013). Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time. Intelligence, 41(6), 843-850.

- Woodley, M. A, te Nijenhuis, J., & Murphy, R. (2015). The Victorians were still faster than us. Commentary: Factors influencing the latency of simple reaction time. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 9, 452