Measurement is central to numerous scientific disciplines, where there is almost an obsession with increasingly precise measurement. However, what many individuals do not realize is how much of the measurements we employ daily is founded on convention or even randomness. Let us pause to reflect on time; as I am drafting this, it is 8:35 am according to the clock on my computer.

This reflects a fleeting record of how far I have advanced through the day, but nearly everything surrounding it is essentially an arbitrary convention established millennia ago. The day itself is the singular fixed aspect, as it represents the term we use in English for the duration it takes the Earth to complete a full rotation on its axis. Dividing this duration into twenty-four equal segments is simply an arbitrary convention introduced by the Ancient Egyptian astronomers. They segmented the night into ten divisions defined by the appearance of specific predetermined stars or star clusters, termed the decans, on the horizon throughout the night. They combined this with the time of dusk and dawn to create twelve segments for measuring the night. After segmenting the night into twelve parts, they analogously divided the day into twelve parts, culminating in a total of twenty-four segments.

This system, however, carries a significant flaw: the durations of day and night are not fixed but fluctuate over the year as the Sun seems to journey along its path from the Tropic of Capricorn to the Tropic of Cancer and back, resulting in solstices, the days with the longest and shortest sunlight, and equinoxes, the two days in spring and autumn where day and night are of equal length. This meant that the lengths of those twelve segments varied throughout the year, lengthening and shortening as the Sun traversed between the Tropics. These changing segments are referred to as temporal or seasonal hours and were the commonly accepted method of time measurement throughout the European Middle Ages. The system of equal or equinoctial hours was introduced by astronomers in antiquity but was only gradually embraced for public use from the fourteenth century onwards in Europe. The fact that we have twenty-four equal hours in one rotation of the day is an arbitrary convention.

What of minutes and seconds, why do we have sixty of each? This tradition originated with the Ancient Babylonians, who utilized a sexagesimal, or base sixty, numbering system. Consequently, the fractions in the initial position represented one-sixtieth of a whole number rather than one-tenth as in the decimal system. The fractions in the second position signified one-sixtieth of a sixtieth or one three-thousand-six-hundredth part of a whole, which corresponds to our minutes and seconds. The terminology derives from Latin pars minuta prima, meaning little parts of the first type that gives us the minute, and pars minuta secunda, meaning little parts of the second type that gives us the second. Once again, these hour divisions are an arbitrary convention.

Hours, minutes, and seconds as we apply them are entirely arbitrary conventions; there is nothing inherent about them. In fact, during the early stages of the French Revolution, the revolutionaries attempted to implement a decimal clock with twenty hours, ten and ten, in lieu of twenty-four, and with one hundred minutes per hour and one hundred seconds per minute. It did not gain traction.

The final convention regarding time measurement is determining when the day starts. We currently begin our day at midnight, in the middle of the night, but this was not always the practice. Various cultures have employed differing starting points for their daily timekeeping; some initiated at midnight, others at dawn around six in the morning, and some at midday, or twelve noon. It is well-known that in Judaism, the day commences at dusk, meaning the Sabbat begins at six in the evening on Friday rather than on Saturday. All a matter of convention, but in this instance, not entirely arbitrary as there is a logical basis for each of the various starting points—dawn, dusk, midday, midnight.

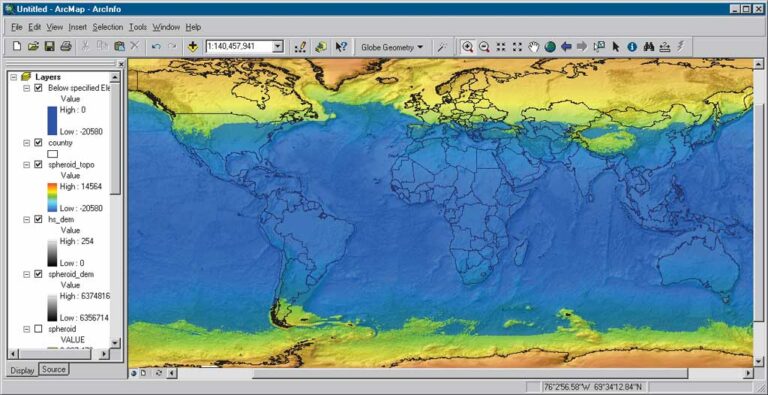

The village from which I am typing this is located at 49° 36´N, 11° 3´O. These are its coordinates within the rectangular grid system of latitude and longitude that we employ to ascertain the locations of places on the Earth’s surface. This system was initially devised by astronomers to pinpoint the positions of celestial entities on the celestial sphere. Subsequently, it was adapted to the globe’s surface to delineate positions on the Earth.

This measuring grid does incorporate some intrinsic anchor points. Assuming the Earth to be a perfect sphere—in reality, it resembles a bumpy potato—the lines of longitude or meridians are the great circles that traverse the north and south poles. Another intrinsic fixed reference is in the great circle at right angles to the meridians around