René Descartes, mainly esteemed as a pivotal figure in contemporary philosophy, also significantly influenced a range of scientific disciplines, such as mathematics, optics, physics, and astronomy. While his philosophical concepts receive admiration, his scientific contributions are often overlooked, perhaps due to inaccuracies in his theories or the rapid developments by successors like Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton, who advanced yet distanced their work from Cartesian notions. Notwithstanding the later prevalence of Newtonian physics, the intellectual competition between Cartesian and Newtonian paradigms continued well into the 18th century.

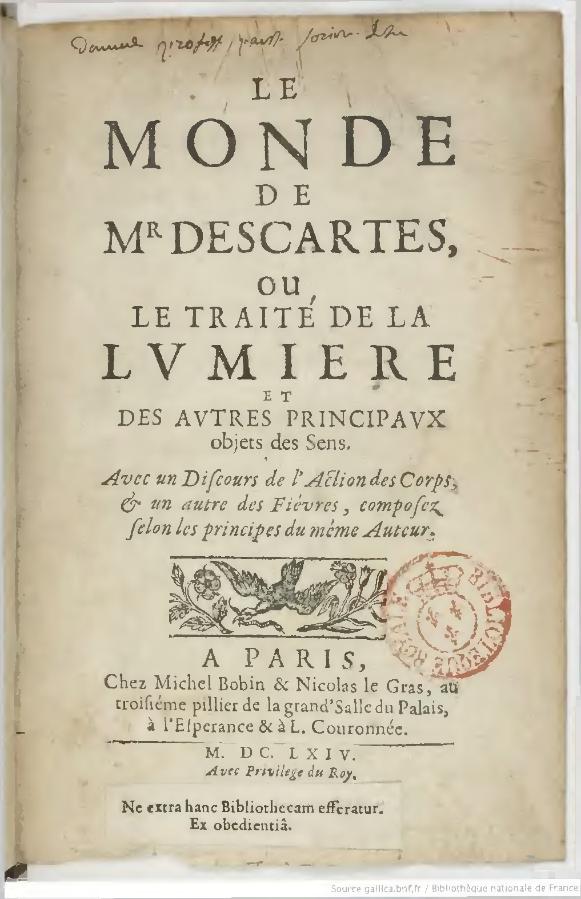

After a notable meeting with Isaac Beeckman in 1618, Descartes adopted the corpuscular mechanical philosophy. During his military training in the Netherlands, he began formulating his methodological approach in “Regulae ad directionem ingenii,” which he intermittently refined until 1628. His journeys throughout Europe enabled him to fund his research and establish connections, particularly with Marin Mersenne. By 1629, Descartes initiated “Le monde,” a detailed cosmographical dissertation aimed at encapsulating the functions of the universe. Concerned about possible repercussions after Galileo’s trial, he chose not to publish its heliocentric claims. Excerpts later appeared in his “Discours de la méthode,” blending his extensive scientific viewpoints.

“Principia Philosophiae,” Descartes’ 1644 endeavor to reformulate Aristotelian education, introduced a consolidation of his theories regarding human existence, material mechanics, cosmology, and earthly sciences. Dismissing the concept of vacuums, Descartes imagined a universe replete with three particle elements, promoting a cosmos driven by direct contact. His three motion laws, while foundational, distinguished themselves from earlier thinkers by prioritizing linear inertia instead of circular. His third law of collisions, which described body interactions, lacked mathematical proof yet proposed the minimum-change principle, highlighting the speculative aspect of Cartesian mechanics.

In the realm of cosmology, Descartes envisioned a divine, vortex-driven universe aligned with his theological beliefs. Celestial bodies, tethered to vortices, moved in synchrony, a theory at odds with Newton’s idea of gravitational attraction. Despite its absence of empirical backing, the mechanical nature of Cartesian vortices was initially favored over Newtonian gravity, indicating an enduring theoretical significance that waned only with the eventual acceptance of Newton’s laws by the mid-18th century. Descartes’ scientific heritage, although eclipsed by his philosophical accomplishments, continues to be an essential segment in the progression of scientific reasoning.