Title: Augustine Ryther and the Dawn of Scientific Instrument Craftsmanship in Elizabethan England

In the evolving landscape of early modern science, characterized by the establishment of observation, measurement, and navigation as empirical disciplines, the role of the scientific instrument craftsman became crucial. In England, however, this profession developed later than on the continent. Innovators like Regiomontanus and Nicolaus Cusanus were already acquiring or creating instruments in regions such as Nürnberg and Northern Italy during the 15th century. Conversely, England did not cultivate a recognized network of instrument makers until the mid-16th century.

Among the trailblazers in this nascent field in England were Thomas Gemini and Humfrey Cole, recognized by historians as key figures in the industry. Nonetheless, one of the most intriguing and significant successors to these early craftsmen was Augustine Ryther, an engraver, cartographer, and scientific instrument maker who thrived between 1576 and 1593. Ryther played an essential role in formalizing mathematical instrument making and map engraving in England throughout the Elizabethan era, a period marked by an increase in scientific exploration and maritime endeavors.

Ryther’s Origins and Influence

Little is definitively understood about Ryther’s beginnings, though 19th-century biographer Lionel Henry Cust theorized he originated from Leeds, Yorkshire, and had some form of cultural or professional connection to cartographer Christopher Saxton. While documentation is limited, Ryther’s known creations place him solidly within a new wave of English artisans whose talents combined practical navigation, military application, and artistic engraving.

Influence on English Cartography and Navigation

Ryther’s earliest identifiable work was as an engraver for Christopher Saxton’s groundbreaking Atlas of the Counties of England and Wales—the first printed atlas of England. Collaborating with both local and Flemish engravers, Ryther created five maps, including those of Durham, Gloucester, Westmorland, York, and a general map of England and Wales. His proud signature, “Augustine Ryther Anglus,” not only proclaimed his identity as an Englishman but also indicated an early manifestation of national contribution in a realm traditionally dominated by continental European scholars.

His output was significant—not merely for its technical skill but also for the national pride it embodied. This was notably demonstrated in Ryther’s engravings for The Mariner’s Mirrour (1588), the English adaptation of Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer’s Dutch Spieghel der zeevaerdt. Commissioned by the Admiralty and translated by Sir Anthony Ashley, this nautical atlas became a crucial navigational guide for English sailors. Ryther’s plates converted Waghenaer’s vision into copper for a distinctly English audience, significantly boosting English navigational knowledge.

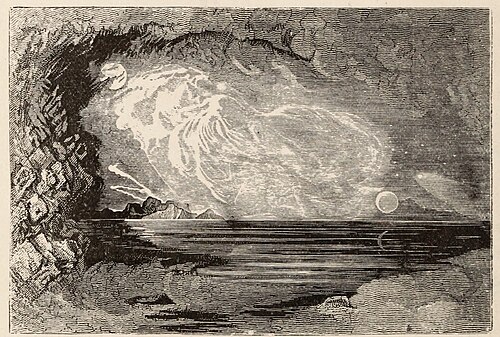

Ryther also created engravings for a vivid and dramatic publication chronicling the Spanish Armada’s defeat. His 1590 translation and illustrated version of Petruccio Ubaldini’s Expeditionis Hispaniorum in Angliam vera Descriptio is a historical artifact as well as a landmark in military cartography. Featuring ten intricate charts detailing the Armada’s journey and eventual defeat, the work illustrates Ryther collaborating closely with Robert Adams, the Queen’s surveyor, and catering to prominent figures involved in England’s naval defense, including Lord Howard of Effingham.

Scientific Instrument Craftsmanship

While Ryther’s map engravings are often the most recognized facet of his career, he also distinguished himself as a creator of mathematical and scientific instruments, although only two of his instruments have survived to this day.

The first is a 1590 theodolite, an advanced surveying tool believed to be inspired by designs from Leonard and Thomas Digges. With capabilities for dual measurement—azimuth and zenith—it allowed for accurate land surveying, a necessity for both civil engineering and military purposes. This specific surviving instrument is thought to have belonged to Sir Robert Dudley and is currently displayed in Florence’s Museo Galileo, reflecting the cross-national legacy of Renaissance science.

The second surviving instrument is a brass compendium from 1588, designed by Ryther, which comprises a universal equinoctial sundial, magnetic compass, and a compilation of latitudes for major European towns. This expertly crafted portable device served as a multifunctional instrument for navigation and timekeeping. Its exquisite craftsmanship highlights Ryther’s technical expertise and implies a clientele of well-traveled gentlemen and sailors.

Collaborations with Influential Figures

Throughout his career, Ryther collaborated with some of the key figures driving the intellectual and scientific evolution of Elizabethan England. His engravings appeared in Thomas Hood’s 1590 publication elucidating the celestial globe in plano—planispheres rendered in two-dimensional formats more user-friendly for seamen compared to celestial globes. These works became vital for imparting knowledge in astronomy and navigation, with Ryther’s artistic touch transforming mathematical concepts into practical teaching tools.

He also contributed to bird’s