Title: Behavioral Exhaustion Amidst Epidemics: Insights from Scientific Research

The COVID-19 outbreak highlighted the importance of social distancing and other precautionary measures. As authorities quickly implemented containment tactics, a term surfaced in public discussions: “behavioral exhaustion.” The UK Government notably referenced it in early 2020 as a justification for postponing stricter health measures, claiming that individuals would eventually tire of social distancing and cease compliance. This notion was met with skepticism from various scientists and analysts, including a widely circulated opinion piece in The Guardian that asserted “’behavioral exhaustion’ lacks a scientific foundation.”

But is that true?

In fact, the issue of how public behavior shifts during epidemics has been the subject of research for many years. While the precise term “behavioral exhaustion” may not be prevalent in peer-reviewed medical studies, the overarching question — do individuals sustain protective actions over time during pandemics? — has been thoroughly investigated by epidemiologists, psychologists, economists, and sociologists.

Let’s explore what the scientific findings reveal.

Grasping Risk Perception

A key factor in how individuals respond during epidemics hinges on their perception of risk. A foundational model, initially published in the 1990s and still frequently cited, outlines how risk perception typically surges during the early phases of an outbreak — often exceeding the actual risk — but then diminishes even as real risk escalates. In essence, we might overreact when a threat emerges but underestimate the genuine danger as we acclimatize to the “new normal.”

This perceptual decline significantly influences behavior. If individuals start to perceive the risk as diminished — even when evidence suggests otherwise — their adherence to public health recommendations may reduce. This represents a genuine phenomenon, even if the term “behavioral exhaustion” does not encapsulate it precisely.

Empirical Evidence: Behavior Change is Observed

Numerous studies across various epidemics – including H1N1 in 2009, SARS, avian influenza, and more recently, COVID-19 – validate that individuals often lessen their preventive actions over time. This encompasses vital behaviors such as hand hygiene, mask usage, and social distancing.

Here are some noteworthy illustrations:

– In Italy, self-reported compliance with hand washing and other actions decreased as the 2009 H1N1 outbreak advanced.

– In Hong Kong, two studies indicated reductions in behavior even as infection rates increased.

– In Malaysia, similar trends were observed, with individuals initially adopting but then reducing their precautionary practices.

Innovative methods have also indirectly assessed changes in behavior. During the 2009 H1N1 outbreak in Mexico, for instance, researchers used television viewership as an indicator of time spent indoors. They discovered that viewership peaked early, implying individuals were remaining home but subsequently declined over time, notwithstanding rising infection rates.

A study concerning air travel revealed a significant uptick in missed flights at the pandemic’s onset, but this trend quickly reversed, indicating that people’s fear and avoidance behavior diminished rapidly. This poses a potential public health challenge, as shared indoor environments facilitate virus transmission.

Cultural, Social, and Economic Influences

Qualitative research, which includes thorough interviews and open surveys, adds depth to these trends. It shows that people do not merely become “tired”; their actions shift in response to increasing social and economic pressures — such as familial duties, job responsibilities, mental health struggles, and financial instability. This nuance enriches the idea of “behavioral exhaustion,” framing it more as a balance between ongoing risk evaluation and daily survival challenges.

Behavioral Modification is Not Guaranteed

Nonetheless, not every study noted a decline in compliance.

– In the Netherlands during a specific outbreak, there was a continuous rise in preventive behaviors without any decrease.

– In Beijing, individuals upheld low-effort practices (e.g., hand washing, airing out rooms) and even amplified high-effort measures (such as purchasing masks).

– Investigations of other outbreaks, including the mosquito-borne disease chikungunya, also observed sustained adherence to protective behaviors.

These results clearly indicate: reductions in protective actions are not a foregone conclusion. They can be counteracted with effective public health communication, support networks, and robust societal frameworks.

Behavior and Epidemic Fluctuations

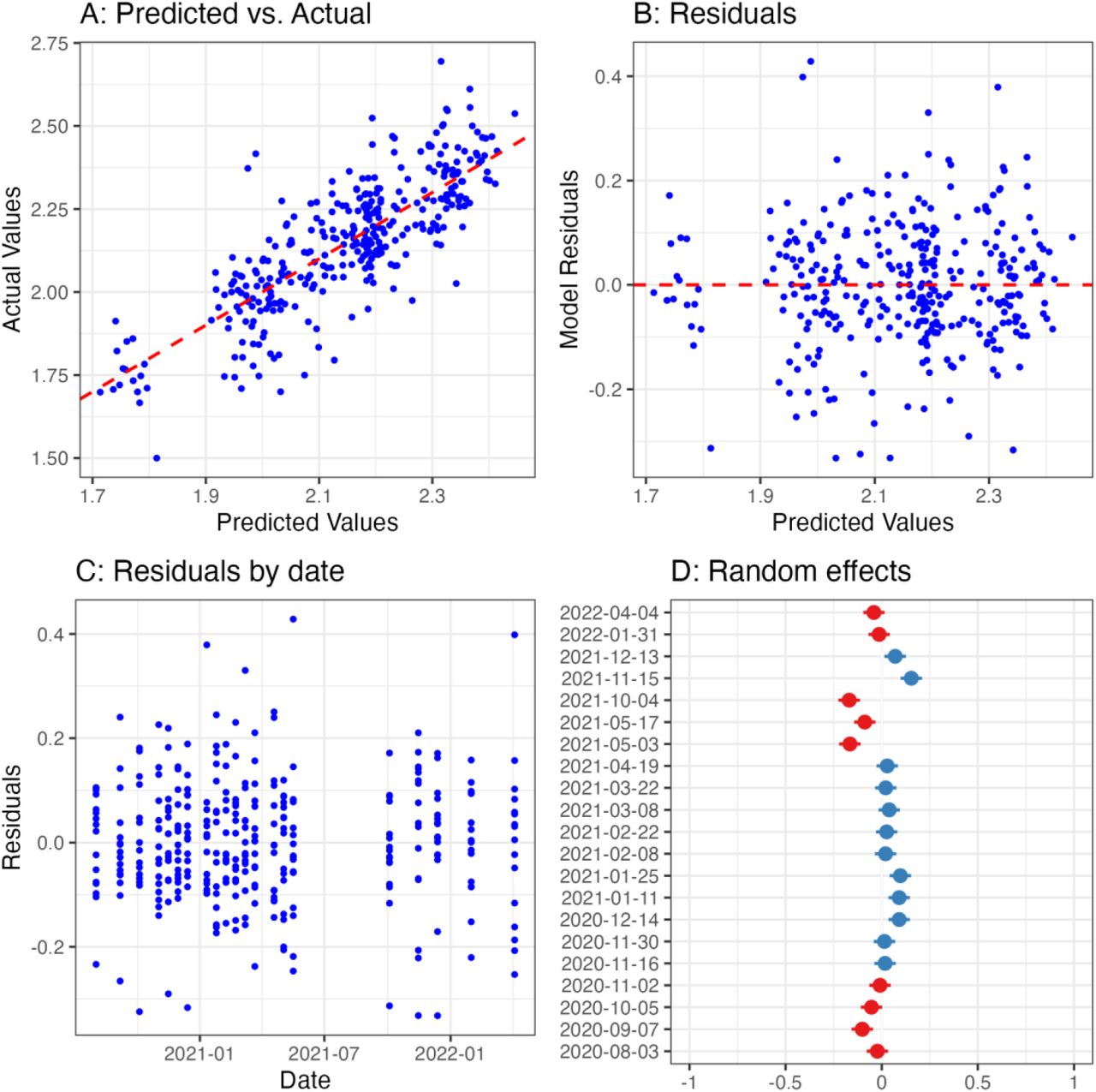

Mathematical models derived from epidemiological data substantiate the notion that human behavior influences pandemic patterns. Epidemics regularly exhibit cyclical trends, and numerous studies link these fluctuations to variations in public adherence. Models analyzing the 1918 influenza pandemic — in the absence of vaccinations — suggest that human behavior likely played a pivotal role in infection trajectories.

Behavior is so central to the dynamics of disease transmission that epidemiologists and economists now develop intricate models featuring behavioral feedback loops. Economists describe this as the “prevalence elasticity” of prevention — the concept that the greater the threat, the more preventive actions are adopted (though not always at the optimal moment or maintained for sufficient duration).

Game theorists have advanced even further, framing the choice to comply or deviate from public health directives as a strategic decision-making process.