Title: Disentangling the Algorithm Fallacy: What Al-Khwarizmi Did—And Didn’t—Create

In recent times, there has been an increasing excitement for acknowledging the global origins of scientific and mathematical knowledge—a movement that seeks to decolonize educational content and embrace contributions beyond the typical Eurocentric framework. While this initiative is both commendable and essential, it has also given rise to a series of simplified or outright false historical assertions. A notably enduring myth—one that, astonishingly, resurfaces in several contemporary academic writings—is the claim that the 9th-century Persian scholar Muḥammad ibn Mūsa al-Khwārizmī “invented the idea of the algorithm.”

Let’s clarify the facts.

Who Was Al-Khwārizmī?

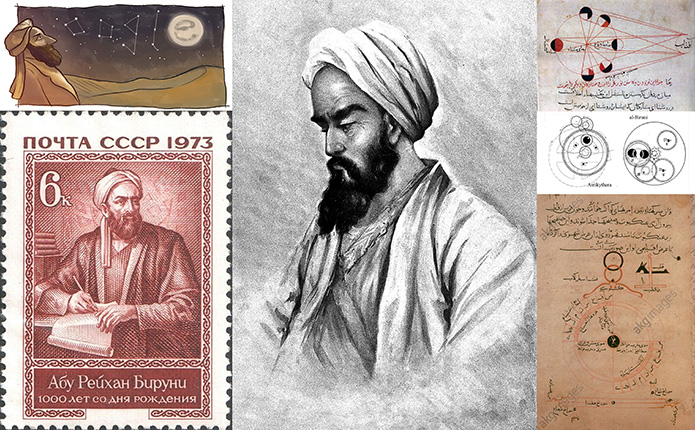

Muḥammad ibn Mūsa al-Khwārizmī (circa 780–circa 850 CE) was a remarkable polymath who contributed his talents to the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Ḥikma) in Baghdad, a preeminent intellectual hub during the Islamic Golden Age. He penned foundational texts on algebra, astronomy, geography, and arithmetic.

His impact on the evolution of mathematics in medieval Europe is profound. When his name was transliterated into Latin, it appeared as “Algoritmi,” and one of his works, translated into Latin, commenced with the now-celebrated phrase “Dixit Algorizmi” (“Thus speaks Al-Khwārizmī”).

This is where the misunderstanding emerges.

What Al-Khwārizmī Actually Accomplished

The Latin translations of al-Khwārizmī’s writings were among the earliest ways Hindu-Arabic numerals were introduced to the Latin-speaking populace. One of the pivotal treatises, often Latinized under various names, including:

– Dixit Algorizmi (released in the 19th century as Algoritmi de Numero Indorum),

– Liber Alchoarismi de Practica Arismetice,

– Liber Ysagogarum Alchorismi,

– and Liber Pulveris,

did not emphasize “the algorithm” as a general concept but rather concentrated on performing arithmetic actions—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—using the recently adopted decimal positional number system from India.

In the medieval Latin language, “algorism” (a variation of his name) came to denote this method: computing with Hindu-Arabic numerals. It was only centuries later that the term “algorithm” expanded in definition to refer to any clearly defined, sequential procedure for solving a problem or completing a task.

Did Al-Khwārizmī Create Algorithms?

No. The cognitive and mathematical notion of a systematic procedural method—that is, an algorithm—significantly predates al-Khwārizmī. The Babylonians utilized such methods in both arithmetic and astronomical computations over two millennia prior to his era. Similarly, ancient Egyptian, Greek, Indian, and Chinese mathematicians employed procedural strategies.

The earliest Babylonian cuneiform records illustrate systematic techniques for resolving quadratic equations and forecasting astronomical events—methods which meet all modern definitions of algorithmic. These are evident examples of algorithm usage long before al-Khwārizmī existed.

What Did Al-Khwārizmī Contribute?

Al-Khwārizmī’s true brilliance lay in organizing established knowledge and presenting it systematically. His exceptional work in algebra—al-jabr wal-muqābala—forms the heart of his mathematical legacy. The term “algebra” itself originates from “al-jabr,” part of the title of his landmark text “Kitāb al-Mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wal-muqābala” (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing). He established systematic approaches for solving linear and quadratic equations and directed the field towards computation independent of geometric interpretation.

Thus, while “algorithm” as a modern term connects etymologically to Al-Khwārizmī, the overarching concept most certainly does not stem from him. Linking him to the creation of the algorithm concept is not only historical misrepresentation but also undermines a broader understanding of ancient mathematical practices.

The Persisting Challenge of Historical Precision

The chronicle of history, particularly in science and mathematics, is notoriously susceptible to distortion, oversimplification, and legend-building. In an era of information where even academic sources may struggle with verifying facts, it becomes increasingly vital to differentiate between lineage and attribution.

Al-Khwārizmī merits significant recognition for his role in transmitting, translating, and expanding upon mathematical concepts from India and other regions. Nevertheless, attributing the invention of the algorithm as a concept to him is inaccurate. At best, one could assert that his name became linguistically associated with procedure-oriented computation in medieval Europe.

“Get Your Facts Straight”

To echo Hulky’s unforgettable expression of exasperation: “If you are going to write about the history