Ancient Egyptian Coffin Art Might Illustrate the Milky Way: A 3,000-Year-Old Revelation Reshapes Early Astronomy

Researchers have uncovered what could be the earliest known depiction of the Milky Way galaxy within ancient Egyptian artistic expressions—an astonishing revelation that may alter our comprehension of how early cultures perceived and represented the universe.

The finding was made by Dr. Or Graur, an astrophysicist from the University of Portsmouth’s Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, while analyzing designs on ancient Egyptian coffins. In a recent study published in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Dr. Graur emphasizes a notable celestial curve illustrated on the coffin of Nesitaudjatakhet—a priestess of the god Amun-Re dating back approximately 3,000 years. This dark, flowing motif seems to reflect the composition of the Milky Way’s “Great Rift,” indicating that ancient Egyptians recognized and artistically integrated this aspect of our galaxy into their religious art.

Symbolism in the Heavens: The Sky Goddess Nut

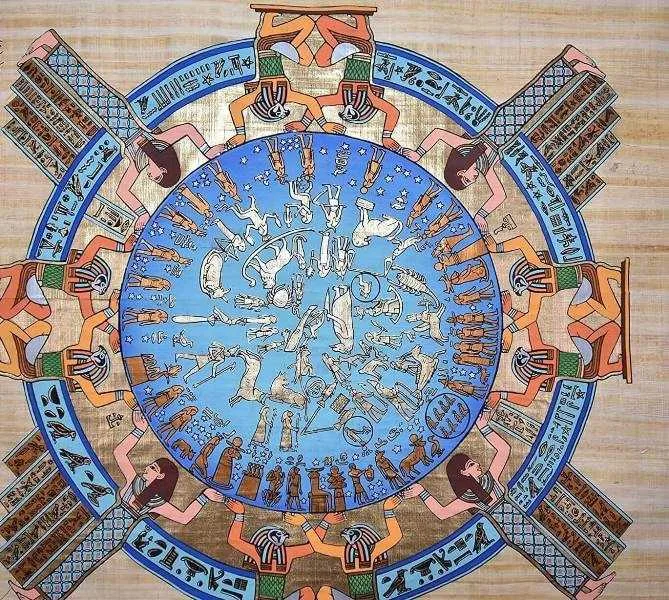

At the core of this discovery lies the figure of Nut, the sky goddess customarily shown stretched across the firmament, embellished with stars on her arched form. In Egyptian lore, Nut’s body constitutes the sky, while her sibling Geb signifies the earth, establishing a cosmological framework for understanding the universe.

During the examination of over 500 coffin artworks from Egypt’s dynastic epochs, Dr. Graur documented 118 instances of what is termed the “cosmological vignette”—a frequent representation of Nut arched over Geb. Nonetheless, an extraordinary example located on the coffin now in Ukraine’s Odessa Archaeological Museum distinguished itself. Spanning Nut’s star-bedecked body is a thick, flowing black band flanked by stars, extending from her feet to her fingertips.

This curve, Dr. Graur elucidates, closely resembles images of the Milky Way’s Great Rift—an evident split traversing the galaxy’s most luminous region where interstellar dust obscures the light of stars. “This undulating curve echoes the Great Rift that divides the Milky Way in two,” Graur remarks.

Visual Astronomy Within a Religious Context

This uncommon stylistic feature may signify more than mere artistic expression. It presents convincing visual proof that the ancient Egyptians acknowledged the striped appearance of our galaxy and inscribed it into their religious symbols. Rather than representing Nut and the Milky Way as one and the same, it seems that the Egyptians depicted the galaxy as one of many celestial elements emblazoned upon the goddess, reinforcing her identity as the sky itself.

This observation bolsters earlier, yet debated, academic suggestions that ancient Egyptians referred to the Milky Way as the “Winding Waterway”—a celestial river cited in pyramid and coffin inscriptions. While textual evidence alone left room for skepticism, this striking visual illustration significantly strengthens the case.

Art Throughout the Ages: A Common Pattern Beyond Egypt

The discovery’s significance is amplified by the existence of similar flowing patterns in other Egyptian burial sites. For example, in Ramesses VI’s tomb, golden bands trace Nut’s arched figure across a painted ceiling, implying a long-standing tradition of incorporating cosmic motifs in art over the centuries.

This pattern is not exclusive to Egypt. Cross-cultural examinations reveal that cultures as far afield as the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni of North America also depicted the Milky Way as a winding or flowing entity on the forms of deities or celestial beings. These worldwide parallels suggest that ancient humans recorded their observations of the night sky in surprisingly uniform symbolic representations.

Reassessing the Ancient Perspective of the Sky

A surprising insight from Dr. Graur’s research is statistical in nature. Only about 25% of known depictions of Nut show her cloaked with stars, implying that many representations might portray the daytime sky rather than the nocturnal—challenging the notion that Egyptian sky art primarily represented the night scene. This finding encourages further inquiry into how ancient Egyptians perceived various phases of the sky and the spiritual or symbolic significance linked to each.

Implications for Science, History, and Culture

The study emphasizes the interconnected nature of science and religion in ancient Egypt, where celestial observations were interwoven with mythological narratives. Rather than separating the sacred from the empirical, early Egyptian astronomer-priests harnessed spiritual symbols to document and communicate knowledge of the heavens.

Dr. Graur’s findings underline the remarkable observational intricacy present in early societies. In an era devoid of advanced optics, ancient peoples recognized—and chose to immortalize—subtle features of the skies, such as the dust lanes and dark shadows that traverse our firmament. This suggests a deep-rooted human curiosity about the cosmos and a rich legacy of scientific awareness encoded within cultural and religious contexts.

Looking Ahead

This revelation adds a fresh perspective to our grasp of the ancient world. It reminds us that while contemporary astronomy relies on satellites and telescopes, many of the same celestial themes and observations were resonated throughout history.