Middle-Aged Adults Boosting Physical Activity May Reduce Alzheimer’s Risk, Pioneering Study Reveals

New studies provide compelling evidence to the increasing agreement that physical activity not only benefits the heart and muscles but may also safeguard the brain. A landmark four-year research project, published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia, indicates that middle-aged individuals who enhance their exercise levels can significantly diminish their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

The research tracked 337 participants aged 45 to 65—all with a family history of Alzheimer’s—over four years, giving a rare insight into how lifestyle modifications during midlife could impact cognitive health years ahead of symptom manifestation.

Exercise Associated with Lower Alzheimer’s Biomarkers

Conducted by researchers at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) and the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center (BBRC), the study focused on changes in participants’ physical activity and brain structure throughout the investigation period.

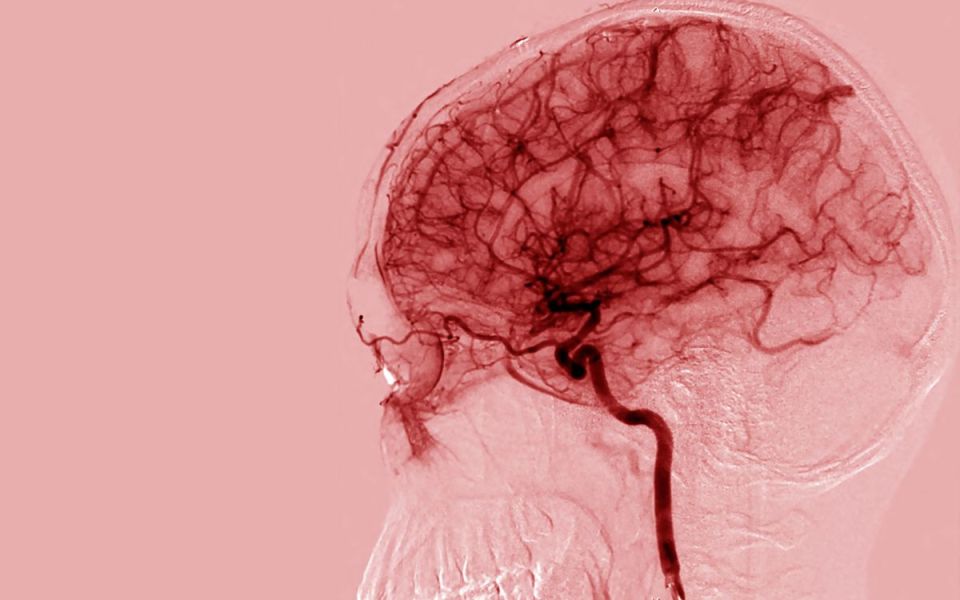

Employing physical activity questionnaires and neuroimaging methods, the researchers observed shifts in the activity levels of these individuals, and subsequently examined brain scans to evaluate beta-amyloid deposits, a significant protein linked to Alzheimer’s.

The results revealed a distinct correlation: participants who increased their activity to meet or surpass the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations—which suggest 150–300 minutes of moderate activity or 75–150 minutes of vigorous activity weekly—showed decreased accumulation of beta-amyloid.

Müge Akıncı, the paper’s lead author and doctoral researcher involved in the study, stated, “a dose-dependent relationship was discovered—the more individuals augmented their activity, the more we noted positive changes in the brain.”

Even Minimal Exercise Is Better Than None

Importantly, those who didn’t fully meet the WHO activity recommendations still experienced cognitive benefits compared to those who were inactive. Notably, these individuals exhibited increased cortical thickness in brain areas crucial for memory and cognitive abilities.

Cortical thinning in the medial temporal lobe is recognized as a sign of early Alzheimer’s disease, thus maintaining brain volume in these areas provides optimism for delaying—or potentially averting—the emergence of symptoms.

“Even small increases in activity can lead to observable enhancements,” Akıncı highlighted. “This underscores that it’s never too late to begin incorporating movement.”

Study Structure Initiated in Midlife—A Vital Period

Participants were divided into five groups based on how their activity levels fluctuated over the four years:

– Consistently Sedentary

– Insufficiently Active

– Consistently Active (meeting WHO guidelines)

– Became Less Active

– Increased Activity to Fulfill WHO Guidelines

The most significant improvements were noted in individuals who raised their exercise levels over time—a promising indication for those beginning from low or no activity.

This midlife stage is increasingly acknowledged as a pivotal moment for interventions that foster long-term brain health. Changes made in one’s 40s and 50s can impact the brain decades before cognitive symptoms appear.

Physical Activity: A Strong Preventive Strategy

Dr. Eider Arenaza-Urquijo, the study’s principal investigator and a researcher at ISGlobal, highlighted broader societal ramifications.

“These results affirm the necessity of encouraging physical activity during middle age as a public health initiative for preventing Alzheimer’s,” she stated. “With global Alzheimer’s cases set to soar, we require accessible, low-cost interventions. Physical activity stands out as one of the most effective strategies available today.”

The study posits that around 13% of Alzheimer’s instances worldwide could be linked to lack of physical activity—emphasizing how crucial exercise could be in decelerating the rise of dementia in aging populations.

A Biological Connection Between Exercise and Brain Health

While the precise biological mechanisms through which exercise influences Alzheimer’s development remain under exploration, the recent findings indicate that activity levels might impact amyloid production or clearance within the brain—aside from other well-known advantages such as better heart health, enhanced social interaction, and lower stress levels.

Previous studies have suggested these benefits, but the incorporation of brain imaging techniques in the Barcelona study brings forth a novel dimension of clinical support.

The researchers utilized PET scans to monitor amyloid buildup and MRI methods to gauge cortical thickness, especially in regions susceptible to degeneration in the progression of Alzheimer’s.

An Actionable Insight: Move More, Age Better

For the millions at risk of Alzheimer’s disease—especially those with a family history—this new research offers an encouraging takeaway: becoming active at any phase of midlife can yield substantial benefits for brain health.

Whether it involves walking, cycling, swimming, or participating in a local exercise class, integrating consistent physical activity into one’s lifestyle could be one of the most economical and accessible approaches to reducing Alzheimer’s risk.

Crucially, even slight increases in movement show potential for cognitive safeguarding, indicating that perfection isn’t essential—progress is what truly matters.

Final Thoughts

As global healthcare systems prepare for a surge in dementia cases, this study highlights the urgent necessity to advocate for preventive health practices. Public policy, educational efforts, and healthcare professionals all have essential roles to play in