**Assessing Response Times: A Timeless Pursuit in Cognitive Psychology**

Response times have served as a fundamental metric in grasping cognitive functions since the late 1800s, even prior to psychology’s establishment as a formal scientific field. These evaluations remain vital in cognitive psychology research, yielding valuable insights into the complexities of human thought processes.

The renowned statistician and eugenicist Francis Galton was one of the pioneers in the systematic assessment of response times. During the late 19th century, Galton amassed a substantial dataset of basic response times from 3,410 individuals. His main focus was to investigate whether response times could act as a marker of personal differences in intelligence. Galton posited that quicker processing times might be linked to greater intelligence, thus providing a rapid means to evaluate cognitive proficiency.

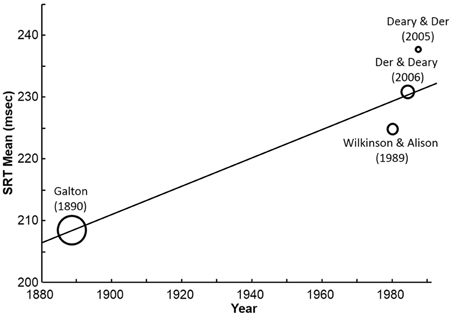

This historical information raises a fascinating query: are contemporary individuals swifter or slower compared to those from Galton’s time? The ramifications of this comparison go beyond simple speed in quick-response situations; they may reveal generational changes in cognitive abilities. In contrast to the generational increases in IQ scores known as the Flynn Effect, which indicates an improvement in intelligence over the years, response time data offers a contrasting viewpoint.

Investigations that juxtapose Galton’s results with current response times imply a deceleration in response times over the century. For example, Silverman’s (2010) research compared response times from 14 studies initiated in 1941 with Galton’s original data, revealing that today’s response times are predominantly longer. Woodley et al. (2015) conducted further analyses of secular trends, demonstrating a consistent reduction in simple response times across four extensive studies over a century. Despite the relatively minor difference of around 20 milliseconds—a considerable variation in response time research—this signifies that modern participants are roughly 10% slower.

This deceleration prompts inquiries regarding its implications. Do these results signify a reduction in cognitive ability, or are they attributable to other influences like heightened cognitive demands from environmental shifts or motivational disparities? Alternatively, could differences in research methodology or participant involvement be factors that affect these outcomes?

In summary, response time research not only provides an intriguing perspective into cognitive processing throughout generations but also compels us to ponder broader issues regarding cognitive development and the impact of cultural and environmental shifts on intelligence. While the findings indicate a deceleration, various interpretations are plausible, and additional inquiry is essential to decipher these intricate dynamics.