**Lost Data in Electron Microscopy: Revealing a Concealed Asset**

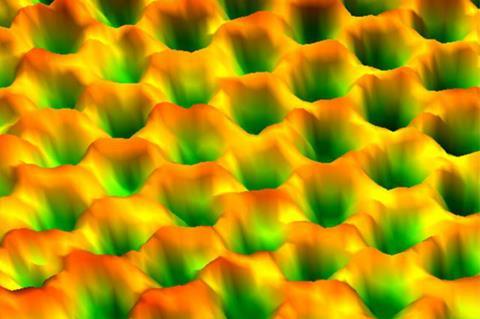

In a surprising discovery, a recent extensive analysis has found that over 97% of electron microscope images remain unreported in peer-reviewed scientific publications. This research carefully examined scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images generated over more than a decade at a single core facility. Unexpectedly, from the 152,000 images assessed, fewer than 3,600 (2%) made their way into scientific journals. Specifically, only 2.6% of SEM images and 1.6% of TEM images appeared in publications, indicating a significant loss of essential microscopy information.

Study co-author Valentine Ananikov, an organic chemist at the Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry in Moscow, emphasizes that this loss cannot be ascribed to image quality. Frequently, the images were of high quality and scientifically valuable, yet only a limited number were selected as “representative” examples for scientific papers. Ananikov stresses that this extensive, unpublished collection represents a “huge untapped asset” in the data-driven age, particularly for artificial intelligence (AI) systems that benefit from large, diverse sets of examples.

As Ananikov suggests, researchers ought to refrain from selectively choosing images to suit their narrative. A more systematic archiving strategy should be implemented to develop comprehensive datasets. He also notes that advancements in tools for managing metadata and organization can ease the previously daunting task of manually sorting and annotating data. Moreover, promoting collaborative databases within laboratories or across institutions could prevent data from being confined to individual computers.

Reese Richardson, a metascience researcher at Northwestern University who did not participate in the study, agrees with the concern that a considerable number of microscopy images remain underutilized. Given the high operational costs of these instruments, Richardson believes that the data from these devices possess significant educational value. However, he contends that disciplinary customs and journal standards often obstruct image publication more than the selectiveness of authors. Richardson advocates for the inclusion of as much information as possible, indicating that the exclusion of potentially useful data is a missed opportunity.

Richardson co-authored a study last year indicating that one in four research papers inaccurately identified SEM instruments, suggesting possible misconduct. Often, vital metadata about specific instruments is left out, making it challenging to identify the equipment used in experiments.

Repositories such as the Electron Microscopy Public Image Archive and the Australian Antarctic Data Center Microscopy Database offer platforms where researchers can archive such images. Richardson underscores the current options available and highlights the need for a cultural shift to adopt them.

In addition to systematic preservation, archiving, and annotating microscopy images using AI and machine learning, linking unused datasets to ongoing research is essential, Ananikov notes. Adequate analysis can reveal new patterns in hidden archives, advancing discovery to new realms.