You may appear fit from the outside, but concealed fat inside your abdomen could be silently obstructing your arteries. This alarming conclusion is drawn from a recent study conducted by McMaster University, which monitored over 33,000 adults in Canada and the UK.

Published on October 17 in Communications Medicine, the research focused on two lesser-known types of fat: visceral fat, which encases internal organs like a thick, active metabolic blanket, and hepatic fat, which accumulates in the liver. Both are associated with diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. However, scientists have previously lacked clarity on how directly these hidden fat reserves lead to arterial damage, which can precede strokes and heart attacks.

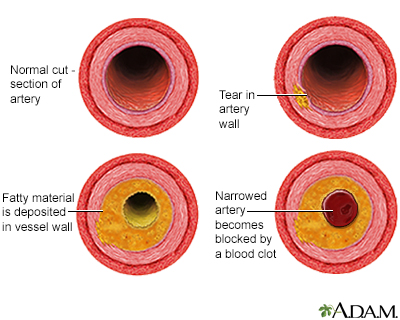

Through advanced MRI scans, researchers evaluated fat distribution and carotid artery health among participants. These arteries supply blood to the brain, and when they thicken or develop plaque, the likelihood of cardiovascular incidents increases significantly. Findings were striking: even after considering traditional risk factors like cholesterol, blood pressure, and smoking, both visceral and liver fat remained independently linked to arterial damage.

“You can’t always tell by looking at someone whether they have visceral or liver fat. This type of fat is metabolically active and harmful; it’s associated with inflammation and arterial damage even in individuals who don’t appear overweight.”

This statement is from Sonia Anand, a vascular medicine expert at Hamilton Health Sciences and corresponding author of the research. She refers to the phenomenon known as “skinny fat,” wherein someone looks slim but possesses harmful internal fat reserves. It serves as a reminder that body mass index (BMI), the standard measure for evaluating obesity, doesn’t provide the complete picture.

Why Visceral Fat Is More Concerning Than You Realize

Visceral fat isn’t idle; it actively secretes inflammatory substances and hormones that disrupt metabolism and induce insulin resistance. The study revealed that for every one standard deviation increase in visceral fat volume, a measurable increase in carotid artery thickness and plaque accumulation occurred. In the UK Biobank cohort, this resulted in a 0.016 millimeter increase in artery thickness for each standard deviation of visceral fat. While this may seem negligible, prior research indicates even a 0.010 millimeter annual decrease in artery thickness can reduce cardiovascular disease risk by roughly 16 percent.

The link with liver fat was weaker, yet still significant. Each standard deviation increase in hepatic fat resulted in a 0.012 millimeter rise in carotid artery thickness in the UK group. Canadian data utilized a different imaging method that assessed artery wall volume instead of thickness, revealing similar patterns, although the connection with liver fat became less consistent after factoring in other risk variables.

Russell de Souza, co-lead author of the study and an associate professor at McMaster, described the results as a wake-up call. “This study indicates that even when accounting for traditional cardiovascular risk factors like cholesterol and blood pressure, visceral and liver fat continue to contribute to arterial damage,” he stated. De Souza contends that healthcare professionals should move beyond BMI and waist size and consider fat distribution more comprehensively.

Implications for Middle-Aged Adults

Participants in the study were middle-aged, averaging between 54 and 57 years. Most were white, and exclusions were made for individuals with contraindications to MRI scans. The researchers accounted for smoking, alcohol intake, diabetes, hypertension, and cholesterol levels, yet the connection between concealed fat and arterial damage persisted.

One possible explanation involves the “fat overflow” theory. When subcutaneous fat storage, which lies just beneath the skin, reaches its limit, excess fat spills into the visceral cavity, inciting inflammation as immune cells invade swollen fat cells. This inflammatory response damages blood vessel walls and accelerates plaque development. Liver fat may also contribute by enhancing the production of small, dense cholesterol particles adept at infiltrating artery walls.

These findings imply that imaging-based evaluations of fat distribution could serve as a valuable method for predicting cardiovascular risk, particularly for individuals who do not conform to the traditional high-risk profile. A person with a normal BMI but elevated visceral fat might be unwittingly accumulating arterial damage. In contrast, someone who is overweight but predominantly holds fat subcutaneously may experience a lower cardiovascular risk than suggested by BMI alone.

Currently, the most effective approach to decrease visceral and liver fat remains unchanged: adhere to a Mediterranean-style diet rich in fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, and vegetables; steer clear of processed foods and added sugars; engage in regular physical activity; and uphold a healthy weight. Some newer medications, such as liraglutide, have displayed potential in reducing visceral fat, and the FDA has recently approved resmetirom for treating advanced liver fat disease. Nevertheless, behavioral changes remain the primary defense.

Due to the cross-sectional design of the study, it cannot establish a definitive causal relationship between visceral fat and arterial damage, merely…