**René Descartes’ Influences on Astronomy and Physics: An In-Depth Exploration**

René Descartes is revered as a pivotal personality in the annals of philosophy, often referred to as the father of modern philosophy owing to his groundbreaking concepts. Nevertheless, Descartes’ impact reaches far beyond philosophy; his contributions to astronomy and physics are equally compelling and merit examination. Although some of his scientific notions were ultimately challenged by contemporaries like Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton, Descartes introduced fundamental ideas that ignited fervent intellectual discussions well into the 18th century.

**Descartes’ Initial Scientific Involvements**

Descartes embarked on his scientific path with a crucial meeting in 1618 with Isaac Beeckman, which cemented his commitment to the corpuscular mechanical philosophy. This philosophy became a foundation for his future scientific explorations. After his time with Beeckman, he enlisted in the army of Maximilian I of Bavaria, during which he also initiated his notable work, “Regulae ad directionem ingenii” or “Rules for the Direction of the Mind,” which molded his systematic methodology in science. This work, though unfinished, established the basis for his scientific and philosophical inquiries and was only published posthumously in 1684.

**Le Monde: The Withheld Masterpiece**

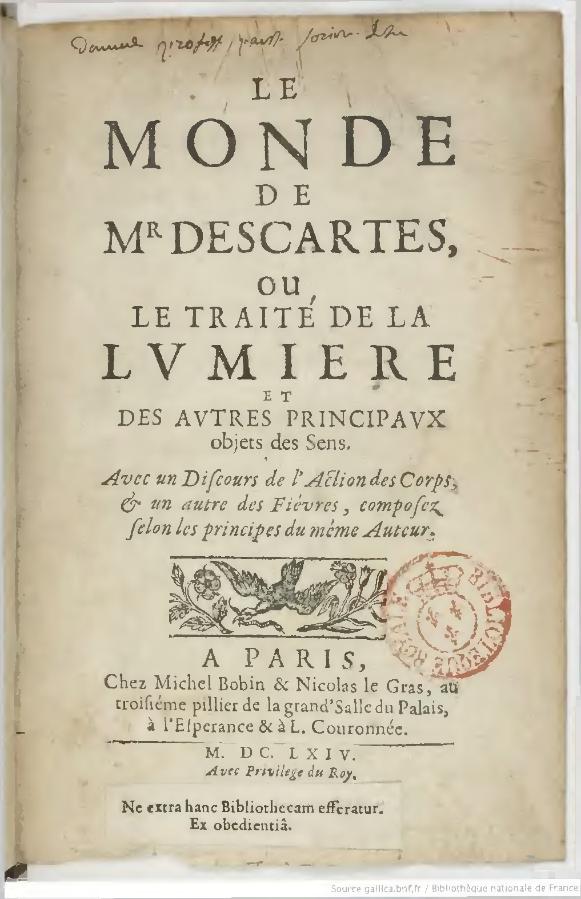

In 1629, Descartes returned to the Netherlands to write an ambitious work on the universe titled “Le monde, ou Traité de la lumière” (The World, or Treatise on Light). Finished in 1633, Descartes refrained from publishing it in light of Galileo’s sentencing for supporting heliocentrism, a viewpoint that resonated with Descartes’ own heliocentric beliefs.

“Le Monde” was revolutionary, advocating significant shifts in understanding the cosmos through 15 interconnected treatises. It examined subjects ranging from the essence of light and planetary motion to the composition of matter and the universe itself. However, to evade the consequences faced by Galileo, Descartes opted to withdraw the manuscript from release. Segments later surfaced in his 1637 publications.

**Principia Philosophiae: Descartes’ Manual of the Universe**

In his subsequent work, “Principia Philosophiae” (Principles of Philosophy), Descartes unified his philosophical thoughts and scientific theories to challenge Aristotelian doctrines. Released initially in 1644, the text outlined his theories in four sections, encompassing human life, mechanics, cosmology, and general science. In this work, Descartes’ laws of motion and theories of collisions were crucial, though incorrect by today’s standards; they were vital stepping stones that would shape future scientific advancements.

1. **Laws of Motion**: Descartes introduced three laws of motion that set the stage for Newton’s later improvements. His concept of inertia, while mistakenly assuming linear movement within his vortex model, presented the idea of objects persisting in their motion unless influenced by an external force.

2. **Cosmology and Vortices**: Descartes’ cosmology was notably defined by his vortex theory. He envisioned a universe filled with moving matter, creating vortices, within which planets revolved amid these swirling flows. Despite being speculative and devoid of empirical backing, this model remained significant, contesting Newtonian gravitational theories for many years due to its strict adherence to mechanistic cause and effect.

**Descartes’ Impact on the Sciences**

Although Descartes’ scientific theories did not endure the tests of time, as later empirically validated theories of Newton replaced his vortex universe model, Descartes’ work propelled scientific reasoning by stressing mechanistic interpretations and the application of logic in understanding the natural world. His thoughts regarding the interactions of bodies and motion sparked a dialogue that continued for generations, paving the way for the precision found in Newtonian and post-Newtonian physics.

In conclusion, René Descartes’ venture into astronomy and physics illustrates his role not merely as a philosopher but also as an early planner of scientific dialogue. His contributions, although eventually overshadowed, played a vital role in steering the trajectory of scientific exploration and represent the progressive transition from metaphysical speculation to mechanistic comprehension during the Scientific Revolution.