Fat lacks glamour. We extract it through liposuction, dispose of it as medical waste, and view it as the body’s storage unit. Yet, researchers in Shanghai recognized it as a living factory that can be repurposed without the traditional genetic modifications. They took typical adult adipose tissue and encouraged it to transform into bone marrow, insulin-producing clusters, and even neural tissue, all without isolating stem cells or manipulating any genes.

The research, published in Engineering by a team from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, outlines a remarkably straightforward method. Human fat was mechanically processed into microfat, then cultured in suspension where it naturally condensed into what the researchers named “reaggregated microfat” or RMF pellets. Over several weeks, these pellets evolved from a loose, yellowish mixture into smooth, firm spheres—resembling tiny pearls of reorganized tissue. The critical aspect wasn’t disassembling the fat into individual cells but allowing it to maintain its internal structure, its “neighborhood,” which facilitated cellular transformation into new identities.

Diabetic Mice Reversed

The most striking test involved diabetes. The team directed RMF pellets along an endodermal path via a four-stage procedure, ultimately producing islet organoids that generate insulin. When these organoids were implanted into diabetic mice, they not only survived but integrated as well. Within two weeks, the mini-organs connected to the organisms’ blood supply and started secreting insulin in response to glucose. Blood sugar levels normalized and remained stable throughout the experiment.

This outcome emphasizes the functional potential present. These were not merely ornamental tissue models; they were active organs executing the very functions of pancreatic islets in a healthy body. The researchers noted the RMF pellets condensing and restructuring their extracellular matrix in manners typically linked to regenerative niches—environments where cells inherently repair and rebuild.

“Thus, these findings underscore the potential of human adipose tissue as a safe, scalable, and clinically applicable source for organoid-based regenerative therapies,” Qingfeng Li states.

The same initial material demonstrated similar versatility in other avenues. When directed towards mesoderm, RMF pellets performed endochondral ossification in immunodeficient mice, creating humanized bone marrow organoids equipped with specialized niches that facilitate blood cell production. After being supplied with human stem cells, these diminutive bone structures supported long-term hematopoiesis—a functional marrow milieu derived from fat. For ectoderm, the pellets developed neurospheres and differentiated into cells showing neuronal and glial markers, illustrating neural-like tissue entirely in vitro.

Bypassing the Stem Cell Bottleneck

Conventional organoid techniques are time-consuming and costly. They depend on pluripotent stem cells that must be isolated, expanded, and carefully directed through differentiation. This process is laborious, difficult to scale, and carries risks such as tumor formation when reprogrammed cells behave improperly. The RMF method avoids these issues by preserving the tissue’s natural architecture. Instead of breaking fat down to individual cells, the technique allows it to reorganize itself using the signaling already present in its structure.

Given that adult fat is plentiful and simple to obtain—often discarded during standard procedures—this approach could scale much more effectively than stem cell methods. It also introduces a personalized medicine perspective: a patient’s own fat could conceivably be used to grow cells specifically suited to their immune system, reducing rejection risk. The researchers demonstrated that RMF pellets enhanced cell proliferation and reorganized their matrix in ways that simulate regenerative environments, indicating that the tissue retains a remarkable degree of plasticity even in adulthood.

The study does not assert that this is ready for clinical application. Further testing is essential, especially concerning long-term safety and the consistency of differentiation among various donors. However, the concept is evident: fat tissue, when processed correctly, behaves less like a fixed cell type and more like moldable raw material. It represents a conceptual transition that could facilitate faster, cheaper, and more accessible organoid production—transforming what was once waste into a foundational element of regenerative medicine.

Engineering: 10.1016/j.eng.2025.06.031

The shift from a patient’s “love handles” to a functional medical organoid entails an intricate mechanical and biological sequence. Unlike traditional approaches that disassemble tissue into individual cells, this method maintains the “neighborhood” of the cells, recognized as the extracellular matrix (ECM).

The RMF Process: From Fat to Pellets

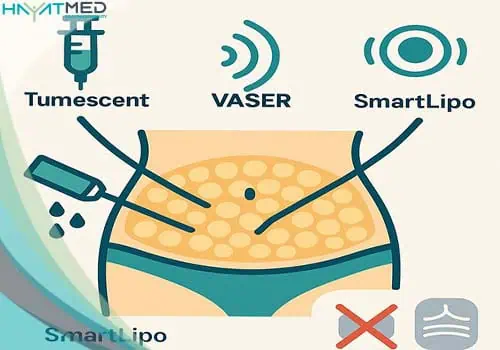

The process begins with lipoaspirate—the fat extracted during liposuction. Rather than discarding it, scientists refine it into Reaggregated Microfat (RMF). The tissue is washed and mechanically processed to form a concentrated slurry of cells and their supporting scaffold. These are then introduced into a specialized suspension culture where they self-assemble into 4-millimeter “RMF pellets.” These pellets serve as the foundational canvas for any organ the scientists aim to cultivate.

Three Paths of Transformation

Once