When patients with weakened immune systems contract herpes infections that fail to respond to standard antiviral treatments, doctors frequently find themselves with limited alternatives. Jonathan Abraham, an infectious disease specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, regularly witnesses this challenge in his practice. His team’s recent study details, for the first time at a molecular level, how a new class of medications physically prevents the virus from replicating itself.

Released on December 29 in Cell, the research discloses how helicase-primase inhibitors (HPIs) deactivate a critical enzyme of the herpes simplex virus. Utilizing cryogenic electron microscopy and optical tweezers, scientists captured both nearly atomic images and real-time videos of the viral machinery halting during replication. Multiple HPIs are already undergoing clinical trials in the U.S., and one has received approval in Japan, but until now, the exact mechanism has been unclear.

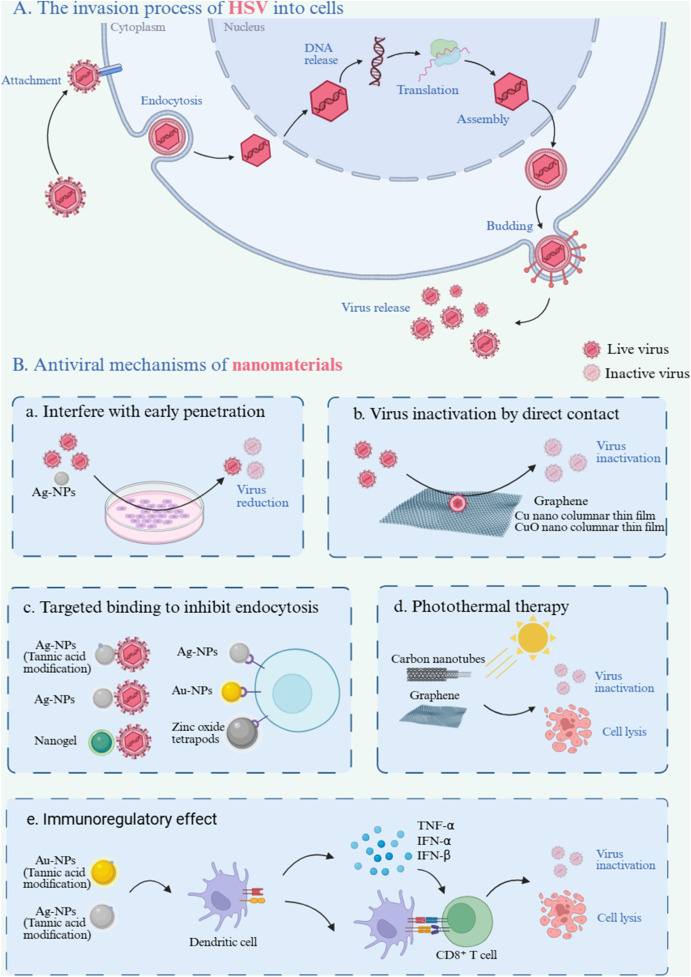

Most herpes medications approved by the FDA focus on the virus’s DNA polymerase, the enzyme responsible for duplicating the viral genome. Resistant strains can develop over time. HPIs target a distinct vulnerability: the helicase-primase, which unwinds the double-stranded DNA and lays down short RNA primers that initiate replication. It functions essentially like a zipper and its pull-tab collaborating to reveal the genome.

“As a clinician, it’s disheartening when medicine can cure a patient of cancer, yet the patient requires immunosuppression that makes them susceptible to a virus that doesn’t respond to the most effective treatments we possess for it,” Abraham states.

Freezing a Shape-Shifter

The helicase-primase continuously alters its shape, making it nearly impossible to image. By tightly binding to the enzyme, the inhibitors effectively immobilized it long enough to be observed. At the Harvard Cryo-EM Center for Structural Biology, the team determined the structure of the HSV-1 helicase-primase attached to several inhibitors at nearly atomic resolution.

Static images alone could not clarify how the drugs prevent replication. Abraham collaborated with Joseph Loparo, a Harvard professor of biological chemistry and molecular pharmacology, to monitor the process. Loparo’s team employed optical tweezers, a method that utilizes focused laser light to hold and manipulate individual molecules. By suspending viral DNA between tiny beads, they witnessed single helicase molecules unzipping DNA strand by strand. When small quantities of inhibitor were introduced, the motion slowed down and ultimately ceased.

The drug functions like a wedge in the gears. It doesn’t completely destroy the enzyme but induces the motor to stall, hindering the virus from duplicating its genome and propagating. Loparo emphasizes that combining high-resolution structural images with real-time monitoring of viral proteins in action was a particular strength of the research.

A Bridge Between Viral Machines

The researchers also discovered how the helicase-primase physically engages with the viral polymerase during DNA replication. They pinpointed a specific amino acid sequence, referred to as the FYNPYL motif, that facilitates the docking of helicase-primase with the polymerase. This molecular handshake is evident across various herpesviruses, including those responsible for shingles and certain malignancies.

By mapping these interaction surfaces, the team unveiled new potential drug targets. Current HPIs are extremely effective against the herpes simplex virus but possess limited applicability. Understanding the physical and chemical characteristics of these binding sites provides researchers with a framework for designing molecules aimed at treating a wider array of DNA viruses.

For doctors managing patients with drug-resistant infections, this research provides something increasingly rare: a clear mechanistic insight coupled with actionable targets for next-generation treatments.

Cell: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.11.041

There’s no paywall here

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of size, enables us to continue providing accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism demands time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep revealing the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!