Psychologists have been measuring reaction times since before psychology existed, and they are still a staple of cognitive psychology experiments today. Typically psychologists look for a difference in the time it takes participants to respond to stimuli under different conditions as evidence of differences in how cognitive processing occurs in those conditions.

Galton, the famous eugenicist and statistician, collected a large data set (n=3410) of so called ‘simple reaction times’ in the last years of the 19th century. Galton’s interest was rather different from most modern psychologists – he was interested in measures of reaction time as a indicator of individual differences. Galton’s theory was that differences in processing speed might underlie differences in intelligence, and maybe those differences could be efficiently assessed by recording people’s reaction times.

Galton’s data creates an interesting opportunity – are people today, over 100 years later, faster or slower than Galton’s participants? If you believe Galton’s theory, the answer wouldn’t just tell you if you would be likely to win in a quick-draw contest with a Victorian gunslinger, it could also provide an insight into generational changes in cognitive function more broadly.

Reaction time [RT] data provides an interesting counterpoint to the most famous historical change in cognitive function – the generation on generation increase in IQ scores, known as the Flynn Effect. The Flynn Effect surprises two kinds of people – those who look at “kids today” and know by instinct that they are less polite, less intelligent and less disciplined their own generation (this has been documented in every generation back to at least Ancient Greece), and those who look at kids today and know by prior theoretical commitments that each generation should be dumber than the previous (because more intelligent people have fewer children, is the idea).

Whilst the Flynn Effect contradicts the idea that people are getting dumber, some hope does seem to lie in the reaction time data. Maybe Victorian participants really did have faster reaction times! Several research papers (1, 2) have tried to compare Galton’s results to more modern studies, some of which tried to use the the same apparatus as well as the same method of measurement. Here’s Silverman (2010):

the RTs obtained by young adults in 14 studies published from 1941 on were compared with the RTs obtained by young adults in a study conducted by Galton in the late 1800s. With one exception, the newer studies obtained RTs longer than those obtained by Galton. The possibility that these differences in results are due to faulty timing instruments is considered but deemed unlikely.

. The Victorians were still faster than us. Commentary: Factors influencing the latency of simple reaction time. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 9, 452.https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00452/full</p>

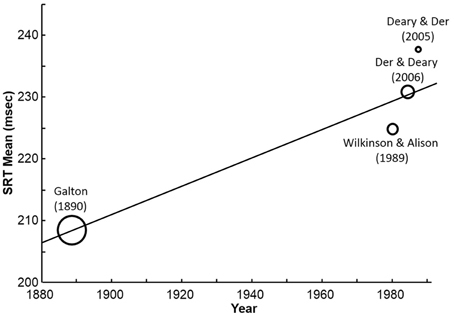

<p> ” data-image-caption data-medium-file=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/did-the-victorians-have-faster-reactions-1.jpg?w=300″ data-large-file=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/did-the-victorians-have-faster-reactions-1.jpg?w=454″ class=”wp-image-34277 size-full” src=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/did-the-victorians-have-faster-reactions.jpg” alt srcset=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/did-the-victorians-have-faster-reactions-1.jpg 454w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/did-the-victorians-have-faster-reactions-1.jpg?w=150 150w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/did-the-victorians-have-faster-reactions-1.jpg?w=300 300w” sizes=”(max-width: 454px) 85vw, 454px”></a><figcaption id=) (Woodley et al, 2015, Figure 1, “Secular SRT slowing across four large, representative studies from the UK spanning a century. Bubble-size is proportional to sample size. Combined N = 6622.”)

(Woodley et al, 2015, Figure 1, “Secular SRT slowing across four large, representative studies from the UK spanning a century. Bubble-size is proportional to sample size. Combined N = 6622.”)So the difference is only ~20 milliseconds (i.e. one fiftieth of a second) over 100 years, but in reaction time terms that’s a hefty chunk – it means modern participants are about 10% slower!

What are we to make of this? Normally we wouldn’t put much weight on a single study, even one with 3000 participants, but there aren’t many alternatives. It isn’t as if we can have access to young adults born in the 19th century to check if the result replicates. It’s a shame there aren’t more intervening studies, so we could test the reasonable prediction that participants in the 1930s should be about halfway between the Victorian and modern participants.

And, even if we believe this datum, what does it mean? A genuine decline in cognitive capacity? Excess cognitive load on other functions? Motivational changes? Changes in how experiments are run or approached by participants? I’m not giving up on the kids just yet.

References:

- Irwin, W. S. (2010). Simple reaction time: it is not what it used to be. American Journal of Psychology, 123(1), 39-50.

- Woodley, M. A., Te Nijenhuis, J., & Murphy, R. (2013). Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time. Intelligence, 41(6), 843-850.

- Woodley, M. A, te Nijenhuis, J., & Murphy, R. (2015). The Victorians were still faster than us. Commentary: Factors influencing the latency of simple reaction time. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 9, 452.