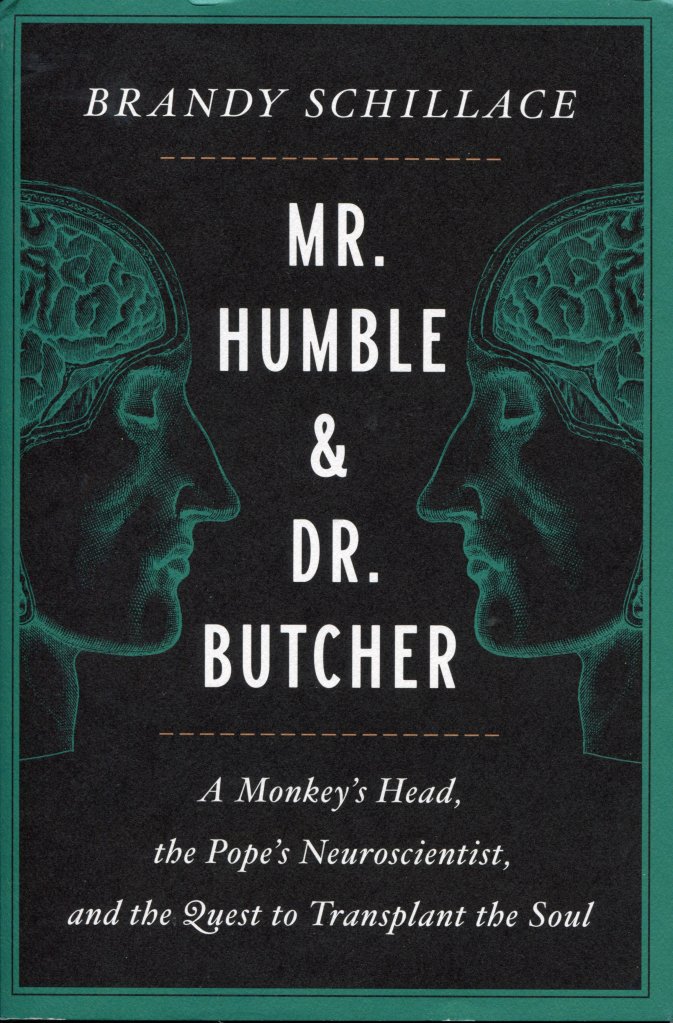

Brain transplants are the subject of science fiction and Gothic horror, right? One of the most famous Gothic horror stories, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus features a brain transplant, of which much is made in the various film versions. But in real life, a fantasy not a reality, or? Wrong, the American neurosurgeon Robert White (1926–2010) devoted most of his working life to the dream of transplanting a human brain, experimenting, and working towards fulfilment of this dream. I’m a voracious reader consuming, particularly in my youth, vast amounts of scientific and related literature, but I had never come across the work of Robert White, which took place during my lifetime. Thanks to Brandy Schillace, this lacuna in my knowledge has been more than filled, through her fascinating and disturbing book Mr. Humble and Dr. Butcher: A Monkey’s Head, the Pope’s Neuroscientist, and the Quest to transplant the Soul[1], which tells in great detail the story of Robert White’s dream and his attempts to fulfil it.

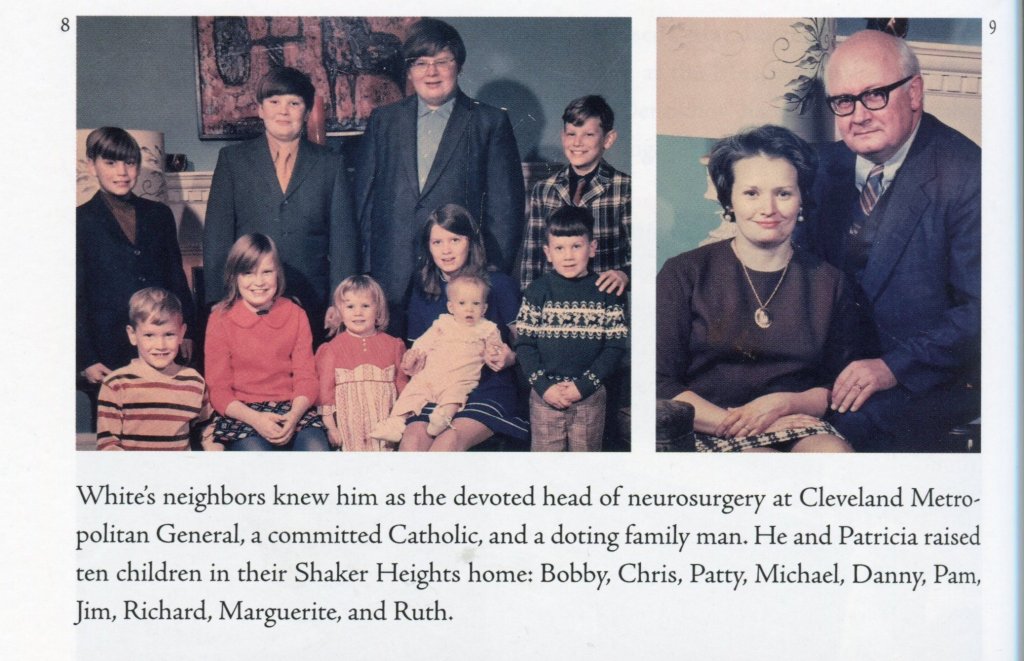

The title is of course a play on the title of Robert Louis Stevenson’s notorious Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the story of a medically induced split personality, with a good persona and an evil one. Here, Mr Humble refers to the neurosurgeon Bob White, deeply religious, Catholic family father and brain surgeon, who always engaged 150% for his patients. A saint of a man, who everybody looked up to and admired.

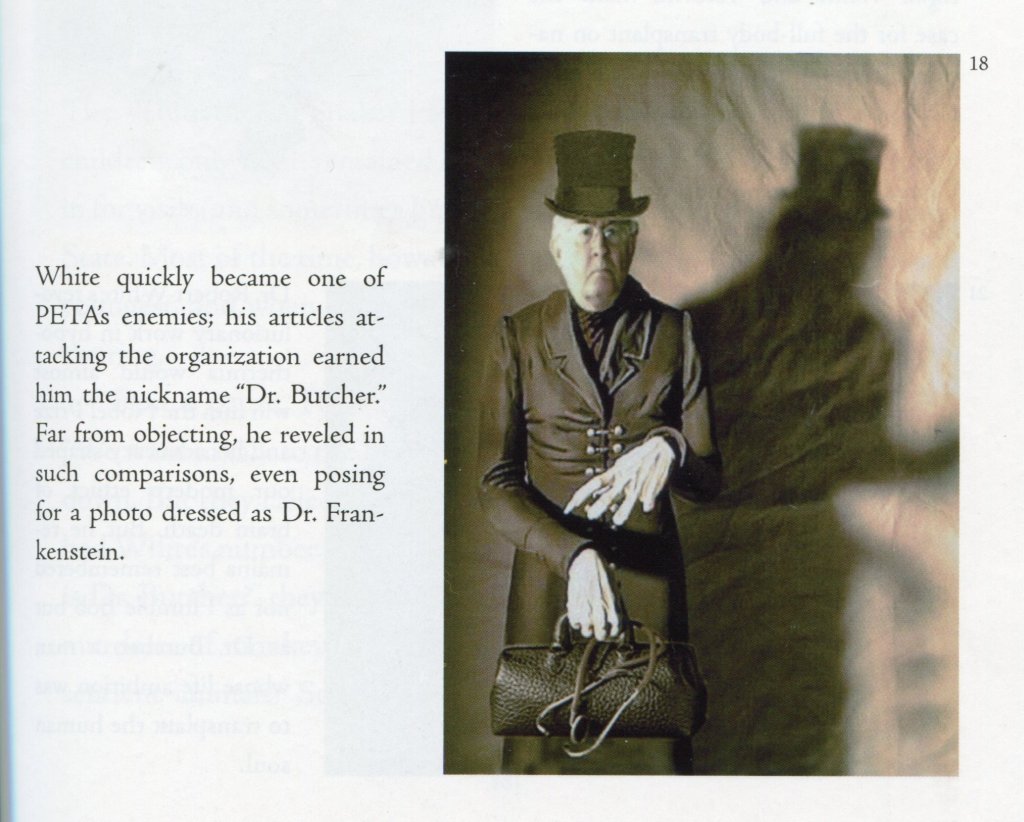

Dr. Butcher refers to the research scientist Dr White, who carried out a, at times truly brutal, programme of animal experimentation on the way to his ultimate goal, the transplantation of a human brain.

Schillace takes us through Robert White’s entire life in detail, illustrating both sides of his personality, at the same time demonstrating that it is not so simple to separate the supposedly contradictory aspect of that personality into the neat division suggested by the title. White both a neurosurgeon and a theoretical neurologists regarded his dream of becoming the first man to carry out a brain transplant, as his greatest medical contribution to the welfare of humanity. Just think what it would mean to a quadriplegic with a healthy and creative brain, trapped in a degenerating body to have their life revitalised by having their brain transferred to the healthy body of a car crash victim, he argued.

Schillace’s book not only tells the life story of the good Doctor Bob, but embeds it deeply in the medical, social, ethical, and political contexts in which it evolved. For example, the reader might justifiably ask how White managed to get research financing, which he did, for what at first glance looks like the script for a Hollywood horror movie. The answer is as surprising as it is simple, the Cold War. We tend to think of the Cold War in terms of nuclear weapons and the space race, but the rivalry between the two superpowers, as they were called, in the post Second World War period covered almost all human activities, including, as it turns out, brain transplants.

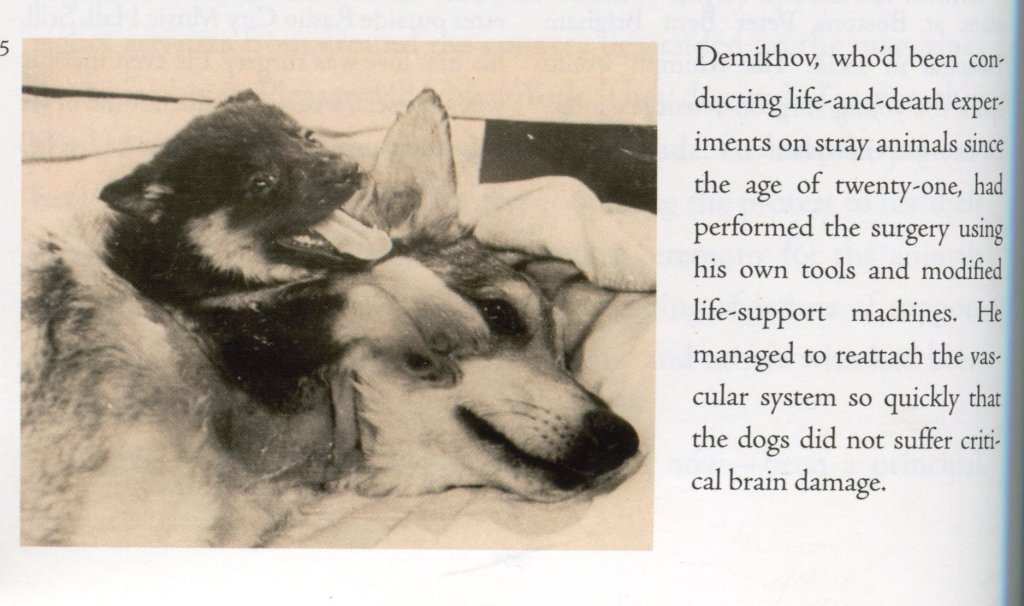

A Russian researcher, Vladimir Demikhov, had carried out numerous experiments on dogs in the post war periods, including transplanting the head of one dog onto the body of a second dog creating a two headed monster that did not live very long. When pictures of Demikhov’s two headed dog appeared in the West, it had a similar impact in the US, as when the Russians launched Sputnik I, panic! “My God, the Russkis are light years ahead of us in their medical research, throw some money at it!” So, Bob White got his brain transplant research generously financed by a US government, firmly convinced that they had to catch up with the commie competition. It would later turn out that Demikhov’s research, dressed up for the Western media, was by no means as revolutionary as it first appeared, and the US didn’t actually have any catching up to do.

Transplant and replacement surgery has become a normal part of our medical world, with kidney transplants or artificial knee joint replacement, for example, now regarded as everyday medical procedures. This was, however, not the case when Bob White started out on his long year research programme, so Schillace also includes as background in her book a fairly detailed sketch of the history of transplant surgery, in particular the problem of organ rejection and the path to its solution.

At the centre of White’s story is his long intensive programme of experiments leading to the transplantation of the head of one monkey onto the body of a second monkey whilst keeping the brain of the transplanted head alive and ticking. Schillace’s detailed descriptions of these crucial experiments are brilliantly written, fascinating, gripping accounts that leave nothing to the imagination and if they don’t leave you feeling queasy, then maybe you should think seriously about your emotive responses. This is the first book review I have ever written that includes a warning to the reader. If you react badly to vivid descriptions of brutal animal experiments, then you should approach this book with caution.

White’s animal experiments led inevitably to confrontations with the animal rights movement, which in the form that we now know it was coming into being in White’s heyday. White met these confrontations head on, even taking part in television debates with his most virulent and articulate critics from the animal rights movement. His arguments were the standard ones of medical researchers, who do experiments on animals, that the benefits to humanity won through such research justifies the suffering to the animals. White’s main opponents on the animal cruelty front were Ingrid Newkirk and Alex Pacheco the couple who founded PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), so Schillace delivers not just a general history of the animal rights movement but a fairly detailed one on the origins of PETA. Their debate with White was one of the cases that helped them from being “five people in a basement” (their own description) to becoming a major voice in animal welfare.

Animal rights and animal welfare were not the only ethical or philosophical themes that White had to deal with in his endeavours to become the first man to transplant a human brain. There were two major ones, the first of which was a question for all transplant surgeons and the second one of which was very central to White’s specific undertaking.

Put simply, the more general problem is when exactly do we die? In terms of transplant surgery, when can the transplant surgeon begin plundering one body to supply spare parts to repair another body and be sure on the one hand that they didn’t kill the donor by taking the parts and on the other hand ensure that those parts are still fresh enough to be used? This is, of course, a complex ongoing debate and one that Schillace deals with more than adequately in her book.

The question specific to White’s work is an even more complex one. If, as most Christian claim, the human body is merely a mortal shell that we abandon when we die, where or what is the real person? What does the real person consist of and where is it situated? Where is the human mind situated and more importantly for believers, where the soul? These questions, and especially the second one, were vitally important to Bob White, who was a devout Catholic. Were the mind and soul both fully contained in the brain, meaning that if one were to transplant a brain, one would transplant a complete human being from one empty shell to another? This is what White wished to believe and a great deal of his research with monkeys was dedicated to trying to prove just this. However, a scientific proof was not enough for White, who needed the blessing of the Catholic Church. In what is a truly fascinating segment of the book, Schillace describes White’s taking up contact with the Church, his meeting with the Pope and his attempt to convince the Church to actively support him in his belief, as to what constitutes real human existence. This contact between the neurosurgeon and the Church led to him becoming a scientific advisor to the Vatican.

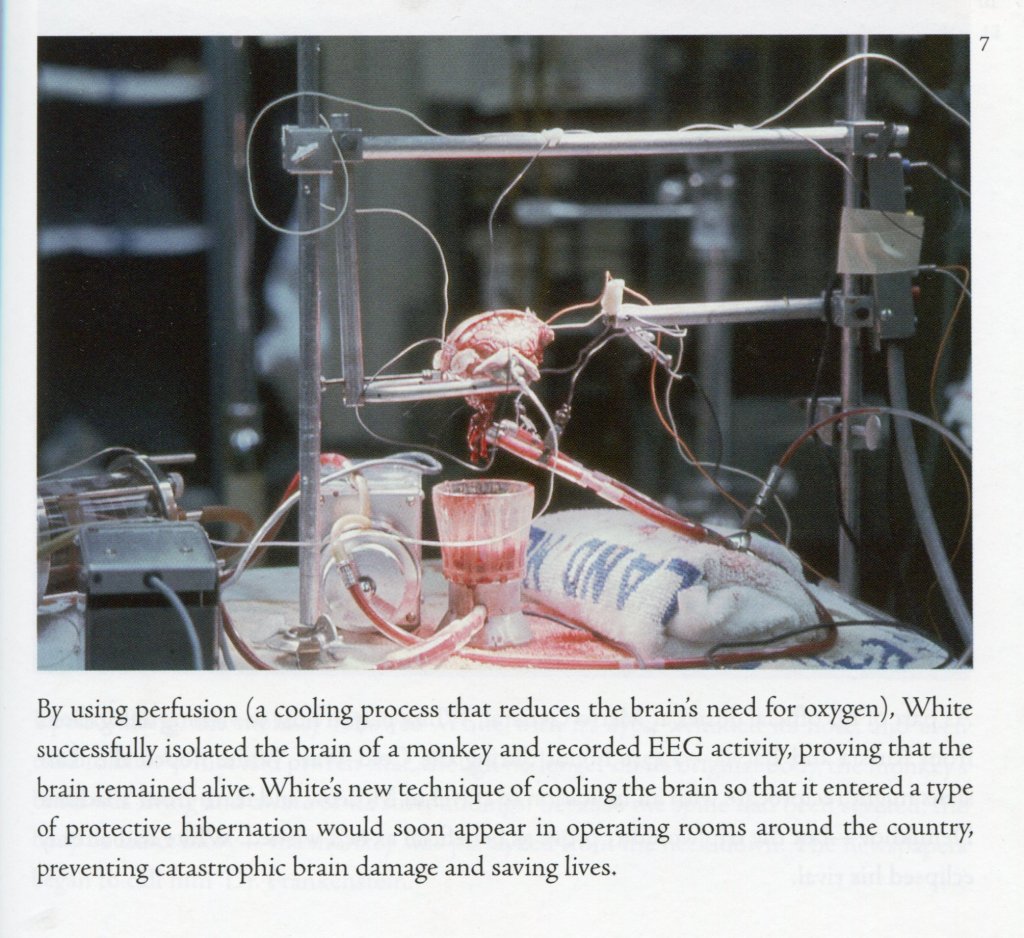

Although he never really came near to realising his lifelong ambition, White’s research into transplant surgery did lead to one very important development in transplant and severe injury surgery. During such surgery there are two main problems, one is the need for high speed because if, for example, you cut off the blood supply you need to restore it very fast if you want to keep your patient alive. The second is the need to be very quick to prevent the deterioration of and further damage to the organs. One method that is used extensively these days is radical cooling, hypothermia, of the affected body parts or the whole body to slow the metabolism and decelerate the any tissue deterioration. This was one of White’s discoveries and it brought him, late in life, a justifiable Nobel Prize nomination. He didn’t win.

The book has endnotes that mostly just record the numerous sources that Schillace consulted in writing this very well research volume. There is, however, no separate bibliography. There is an extensive and useful index. The book is rounded out with a selection of both black and white and colour photos.

Schillace, who is a world class story teller pulling the reader along with her pulsating narrative, has written a truly excellent book. A straightforward account of Bob White’s life and work would make for a fascinating narrative but the amount of context in which Schillace has embedded her narrative make this book so much more. She takes her readers down numerous intriguing rabbit holes, leaving this reader at least with the desire to read up on a dozen random topics.

This is a book for anybody who likes good quality, stimulating, informative history that will leave the reader with a hat full of philosophical conundrums about life and what exactly it is. Don’t take my word for it, get hold of a copy and read it!

[1] Brandy Schillace, Mr. Humble and Dr. Butcher: A Monkey’s Head, the Pope’s Neuroscientist, and the Quest to transplant the Soul, Simon & Schuster, New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, New Delhi, 2021