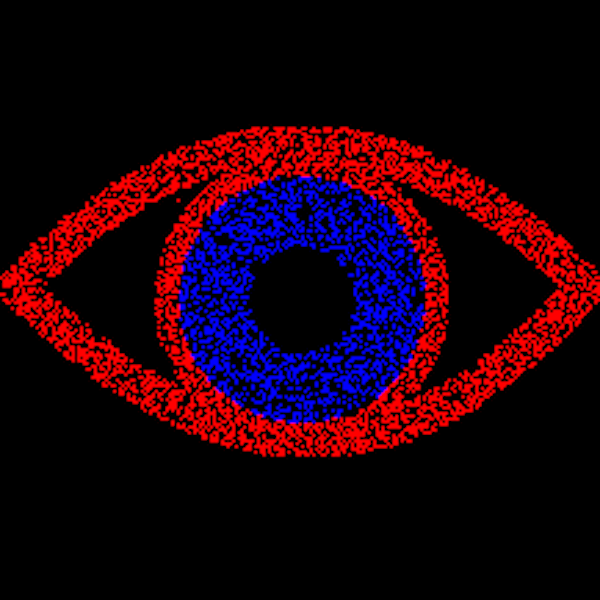

The effect varies for different people. Take a moment and look at this. Some people don’t see anything special: just a blue pupil in a red eye.

For me though, there is an incredibly strong depth illusion – the blue and the red appear as if they are at different distances.

I can enhance the effect by blinking rapidly, turning the brightness up on my screen and viewing in a dark room. Sometimes it disappears for a few seconds before snapping back in. Because the colours appear at different depths they even appear to glide separately when I move my head from side to side, something which is obviously impossible for a static image.

The effect is called chromostereopsis and it is weirding me out, for several reasons.

The first is that I’d thought I’d seen all the illusions, and this one is completely new to me. Like, guys, did you all know and weren’t telling?

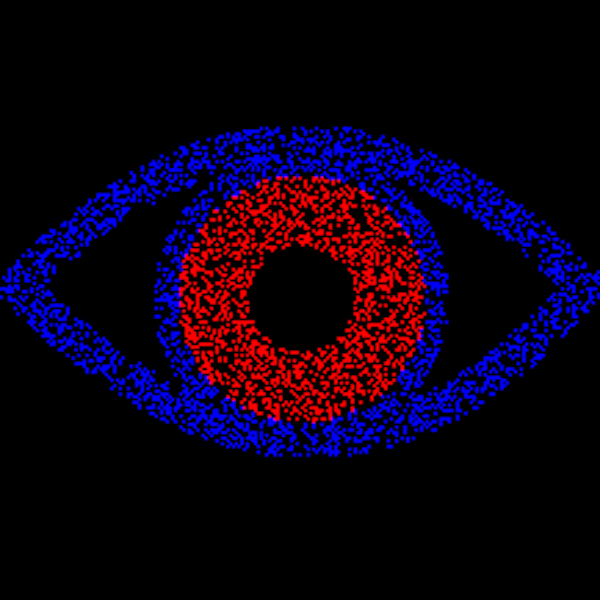

The second is that there are big individual differences in perception of the effect. This isn’t just in terms of strength, although obviously I’m one of those it hits hard. People also differ in which colour looks closer. For most people it is red, with blue looking deeper or further away. I’m in the minority, so if you’re like me this reverse of the image above should look more natural: the pupil set deeper than the surrounding eye.

The third reason this effect is weird to me is that stereo-depth illusions usually require two images, separately presented to each eye. This is how 3D cinema works – you wear red-green or polarising classes and the 3D parts of the film present two superimposed images, each image filtered out by only one lens, putting slightly different images in each eye. Your visual system combines the image and ‘discovers’ depth information, adding to the 3D perception of the objects shown. The superimposed images are why the film looks funny if you take the glasses off.

Chromostereopic illusions are true stereo illusions – they require the information to be combined across both eyes. There are many depth illusions which aren’t stereo illusions, but this isn’t one of them. You can prove this to yourself by making the effect disappear by closing one eye. The image stays the same, but it has to go in both eyes for the illusion of depth to occur. You can also try and find someone who is “stereoblind” and show them the illusion. A small percentage of the population don’t combine information across both eyes, and so only perceive depth via the other, monocular, cues. Our visual system is so adept at doing this that many people live their whole lives without realising they are stereoblind (although I suspect they tend not to go into professions which require exact depth perception, like juggling).

The way chromostereopsis works is not entirely understood. Even the great Michael Bach, who wrote for the Mind Hacks book, describes the explanation for the phenomenon as ‘multi-varied and intricate‘. That red and blue are at opposite ends of the light spectrum has something to do with it, and the consequent fact that different wavelengths of light will be focussed differently on the back of the eyes. This may also be why some people report that their glasses intensify the effect. The luminance of the image and the background also seems to be important.

The use of colour has a long history in art, from stained glass windows to video games, and probably many visual artists have discovered chromostereopsis by instinct. One of my favourite real-world uses is the set of the panel show Have I Got News For You:

For more on Depth Illusions, see the Mind Hacks book, chapters 20,22,24 and 31. For how I made the images, see the colophon on my personal blog.

More on the science: Kitaoka, A. (2016). Chromostereopsis. in Ming Ronnier Luo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology, Vol.1, New York; Springer (pp. 114-125).