If you go beyond the big names, big events version of the history of science and start looking at the fine detail, you can discover many figures both male and female, who also made, sometime significant contribution to the gradual evolution of science. On such figure is the man who inspired the title of this blog post, the splendidly named Sir Kenelm Digby (1603–1665), who made contributions to a wide field of activities in the seventeenth century.

</p>

<p> ” data-medium-file=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-swashbuckling-philosophical-alchemist-15.jpg” data-large-file=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-swashbuckling-philosophical-alchemist-16.jpg?w=500″ src=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-swashbuckling-philosophical-alchemist.jpg” alt class=”wp-image-9012″ srcset=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-swashbuckling-philosophical-alchemist.jpg 767w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-swashbuckling-philosophical-alchemist-14.jpg 112w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-swashbuckling-philosophical-alchemist-15.jpg 225w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-swashbuckling-philosophical-alchemist-16.jpg 1351w” sizes=”(max-width: 767px) 100vw, 767px”></a><figcaption>Kenelm Digby (1603-1665) Anthony van Dyck Source: Wikimedia Commons</figcaption></figure>

<p>To show just how wide his interests were, I first came across him not through my interest in the history of science, but through my interest in the history of food and cooking, as the author of an early printed cookbook, <em>The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kt. Opened</em> (H. Brome, London, 1669).</p>

<figure class=)

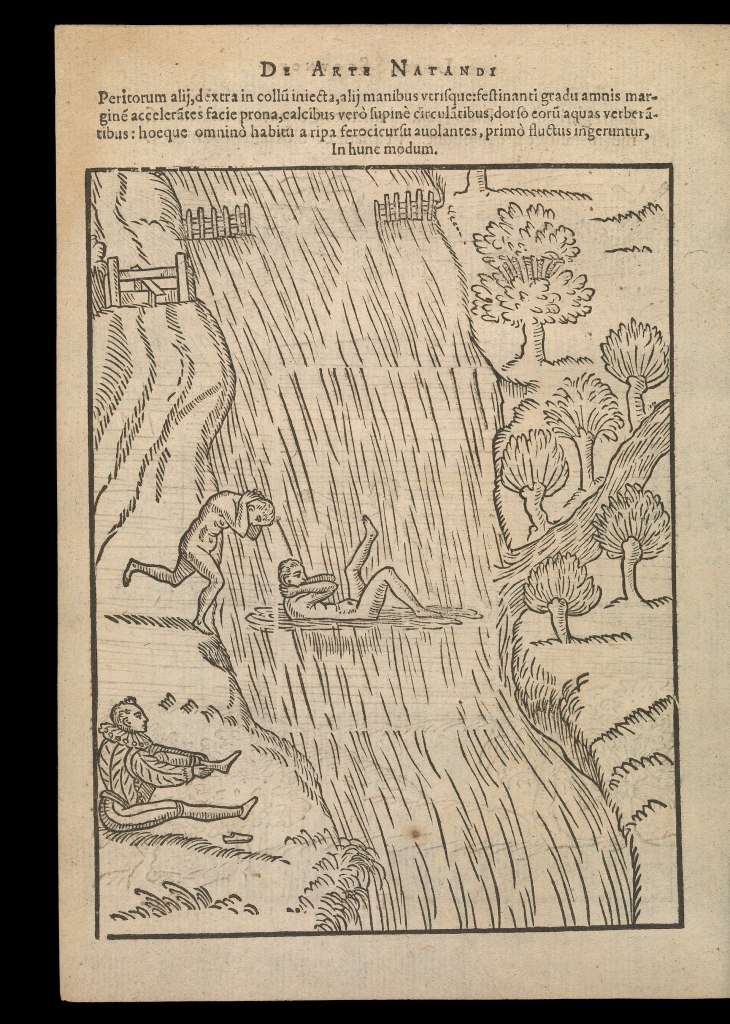

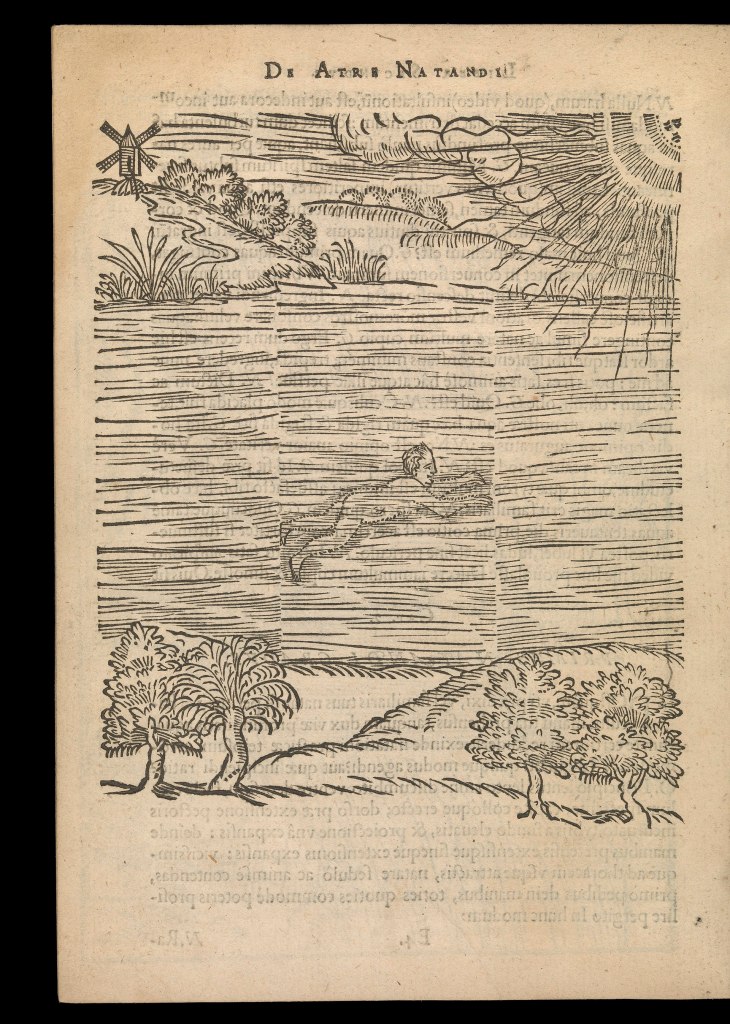

Born 11 June in Gayhurst, Buckinghamshire, in 1603 into a family of landed gentry noted for their nonconformity, he, as we will see, lived up to the family reputation. His grandfather Everard Digby (born c. 1550) was a Neoplatonist philosopher in the style of Ficino, and fellow of St John’s College Cambridge, (Fellow 1573, MA 1574, expelled 1587), who authored a book that suggested a systematic classification of the sciences in a treatise against Petrus Ramus, De Duplici methodo libri duo, unicam P. Rami methodum refutantes, (Henry Bynneman, London, 1580, and what is considered the first English book on swimming, De arte natandi, (Thomas Dawson, London, 1587). The latter was published in Latin but translated into English by Christopher Middleton eight years later.

His father Sir Everard Digby (c. 1578–1606) and his mother Mary Mulsho of Gayhurst were both born Protestant but converted to Catholicism.

His father was executed in 1606 for his part in the Gunpowder Plot and Kenelm was taken from his mother and made a ward first of Archbishop Laud (1573–1645) and later of his uncle Sir John Digby (1508-1653), who took him on a sixth month trip (August 1617–April 1618) to Madrid in Spain, where he was serving as ambassador.

Returning from Spain, the fifteen-year-old Kenelm entered Gloucester Hall Oxford, where he came under the influence of Thomas Allen (1542–1632).

100vw, 341px”></a><figcaption>Thomas Allen by James Bretherton, etching, late 18th century Source: wikimedia Commons</figcaption></figure>

<p> Thomas Allen was a noted mathematician, astrologer, geographer, antiquary, historian, and book collector. He was connected to the circle of scholars around Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland (1564–1632), the so-called Wizard Earl, through whom he became a close associate of Thomas Harriot (c. 1560–1621). Through another of his patrons Robert Dudley, Early of Leicester, (1532–1588) Allen also became an associate of John Dee (1527–c. 1608). Allen had a major influence on Digby, and they became close friends. When he died, Allen left his book collection to Digby in his will: </p>

<blockquote class=)

… to Sir Kenelm Digby, knight, my noble friend, all my manuscripts and what other of my books he … may take a liking unto, excepting some such of my books that I shall dispose of to some of my friends at the direction of my executor.

Digby donated this very important collection of at least 250 items, which contained manuscripts by Roger Bacon, Robert Grosseteste, Richard Wallinford, amongst many others to the Bodleian Library.

Digby left Oxford without a degree in 1620, not unusual for a member of the gentry, and took off on a three-year Grand Tour of the continental. In France Maria de Medici (1575–1642) is said to have cast an eye on the handsome young Englishman, who faked his own death and fled France to escape her clutches. In Italy he became accomplished in the art of fencing. In 1623 he re-joined his uncle in Madrid, this time for a nearly a year and became embroiled in the unsuccessful negotiations to arrange a marriage between Prince Charles and the Infanta Maria. Despite the failure of this mission, when he returned to England in 1623, the twenty-year-old Kenelm was knighted by James the VI &I and appointed a Gentleman to Prince Charles Privy Chamber at the time converting to Anglicanism. In 1625 he secretly married his childhood sweetheart Venetia Stanley (1600–1633). They had two sons Kenelm (1526) and John (1627) before the marriage was made public.

Out of favour with Buckingham, Digby now became the swashbuckler of the title. Fitting out two ships, the 400-ton Eagle under his command and the 250-ton Barque under the command of Sir Edward Stradling (1600–1644), he set off for the Mediterranean to tackle the problem of French and Venetian pirates, as a privateer, a pirate sanctioned by the crown.

Capturing several Flemish and Dutch prize on route, on 11 June 1628 they attacked the French and Egyptian ships in the bay of Scanerdoon, the English name for the Turkish port of Iskender. Successful in the hard-fought battle, Digby returned to England with both ships loaded down with the spoils, in February 1629, where he was greeted by both the King and the general public as a hero. He was appointed a naval administrator and later Governor of Trinity House.

The next few years were spent in England as a family man surrounded by a circle of friends that included the poet and playwright Ben Johnson (1572–1637), the artist Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), the jurist and antiquary John Seldon (1584–1654), and the historian Edward Hyde (1609–1674) amongst many others. Digby’s circle of friends emphasises his own scholarly polymathic interests. His wife Venetia, a notable society beauty, died unexpectedly in 1633 and Digby commissioned a deathbed portrait and from van Dyck and a eulogy by Ben Johnson, now partially lost.

Digby stricken by grief entered a period of deep mourning, secluding himself in Gresham College, where he constructed a chemical laboratory together with the Hungarian alchemist and metallurgist János Bánfihunyadi (Latin, Johannes Banfi Hunyades) (1576–1646), where they conducted botanical experiments.

In 1634, having converted back to Catholicism he moved to France, where he became a close associate of René Descartes (1596–1650). He returned to England in 1639 and became a confidant of Queen Henrietta Maria (1609–1669) and becoming embroiled in her pro-Catholic politics made it advisable for him to return to France.

Here he fought a duel against the French noble man Mont le Ros, who had insulted King Charles, and killed him. The French King pardoned him, but he was forced to flee back to England via Flanders in 1642. Here he was thrown into goal, however his popularity meant that he was released again in 1643 and banished, so he returned to France, where he remained for the duration of the Civil War.

Henrietta Maria established a court in exile in Paris in 1644 and Digby was appointed her chancellor. In this capacity he undertook diplomatic missions on her behalf to the Pope. Henrietta Maria’s court was a major centre for philosophical debates with William Cavendish, the Earl of Newcastle, his brother Charles both enthusiastic supporters of the new sciences, William’s second wife Margaret Lucas, who had been one of Henrietta Maria’s chamber maids and would go on to great notoriety as Margaret Cavendish prominent female philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, and from the French side, Descartes, Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655), Pierre Fermat (1607–1665), and Marin Mersenne. Digby was in his element in this society.

After unsuccessfully trying to return to England in 1649, in 1653, he was granted leave to return, perhaps surprisingly he became an associate of Cromwell, whom he tried, unsuccessfully, to win for the Catholic cause. He spent 1657 in Montpellier to recuperate, but returned to England in 1658, where he remained until his death.

He now became friends with John Wallis (1616–1703), Robert Hooke (1635–1703), and Robert Boyle (1627–1691) and was heavily involved in the moves to form a scientific society, which would lead to the establishment of the Royal Society of which he was a founder member. On 23 January 1660/61 he read his paper A discourse concerning the vegetation of plants before the founding members of the Royal Society at Gresham College, which was the first formal publication to be authorised by that still unnamed body. The Discourse would prove to be his last publications, as his health declined, and he died in 1665.

Up till now the Discourse is the only publication that I’ve mentioned, but it was by no means his only one. Digby was a true polymath publishing works on religion, A Conference with a Lady about choice of a Religion(1638), Letters… Concerning Religion (1651), A Discourse, Concerning Infallibility in Religion (1652). Autobiographical writings including, Articles of Agreement Made Betweene the French King and those of Rochell… Also a Relation of a brave and resolute Sea Fight, made by Sr. Kenelam Digby (1628), and Sr. Kenelme Digbyes honour maintained (1641). Critical writings on Sir Thomas Browne, Observations upon Religio Medici (1642), and on Edmund Spencer, Observations on the 22. Stanza in the 9th Canto of the 2d. Book of Spencers Faery Queen (1643).

What, however, interests us here are his “scientific” writings. The most extensive of these is his Two Treatises, in One of which, the Nature of Bodies; in the Other, the Nature of Mans Soule, is looked into: in way of discovery, of the Immortality of Reasonable Soules originally published in Paris in 1644 but with further editions published in London in 1645, 1658, 1665, and 1669. Although basically still Aristotelian, this work shows the strong influence of Descartes and contains a positive assessment of Galileo’s Two New Sciences, which was still relatively unknown in England at the time. It also contains a form of mechanical atomism, which, however, is different to those of Epicure or Descartes.

Digby’s most controversial work was his A late discourse made in solemne assembly … touching the cure of wounds by the powder of sympathy, originally published in French in 1658 and then translated into English in the same year. This was a discourse that Digby had held publicly in Montpellier during his recuperation there.

This was a variation on Weapon Salve, an ointment that was applied to the weapon that caused a wound rather than to the wound itself. Digby was by no means the first to write positively about this supposed cure. It has its origins in the theories of Paracelsus and the Paracelsian physician Rudolph Goclenius the Younger (1572–1621), professor at the University of Marburg, first published on it in his Oratio Qua defenditur Vulnus Non Applicato Etiam Remedio, in 1608. In England the divine William Forster (born 1591), the physician and alchemist Robert Fludd (1574–1637), and the philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626) all wrote about it before Digby, but it was Digby’s account that attracted the most attention and ridicule. In 1687, an anonymous pamphlet suggested using it to determine longitude. A dog would be wounded with a blade and placed aboard a ship before it sailed. Then every day at noon the weapon salve would be applied to the blade causing the dog to react, thus tell those on board that it was noon at their point of departure.

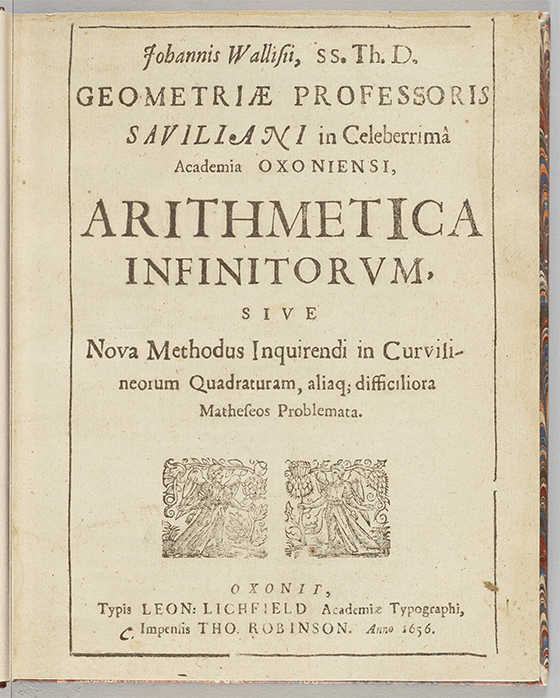

Also in 1658, John Wallis dedicated his Commercium epistolicum to Digby who was also author of some of the letters it contained.

In 1657, Wallis had published his Arithmetica Infinitorum, an important contribution to the development of calculus.

Digby brought the book to the attention of Pierre Fermat and Bernard Frénicle de Bessy (c. 1604 – 1674) in France, Fermat wrote a letter to the English mathematician, posing a series of problems to be solved. Wallis and William Brouncker (1620–1684), who would later become the first president of the Royal Society, took up the challenge and an enthusiastic exchange of views developed between the French and English mathematicians, with Digby acting as conduit for the correspondence. Wallis collected the letter together and published them as his Commercium epistolicum.

As already stated, A discourse concerning the vegetation of plants was Digby’s final publication and was to some extent his most interesting. Digby was interested in the question of how to revive dying plants and his approach was basically alchemical. He argued that saltpetre was necessary to the process of revival and that it attracted vital air, which is the food of the lungs. He is very obviously here close to discovering oxygen and in fact he supports his argument with the information that Cornelius Drebbel had used saltpetre to refresh the air in his submarine. In the paper he also hypothesises something very close to photosynthesis. Others such as Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580–1644) were conducting similar investigations at the time. These early investigations would lead on in the eighteenth century to the work of Stephen Hales (1677–1761) and the pneumatic chemists of the eighteenth century.

Digby made no major contributions to the advancement of science, but he played a central role as facilitator and mediator between groups of philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists promoting and stimulating discussions in both France and England in the first half of the seventeenth century. He also played an important role in raising the awareness in England of the works of Descartes and Galileo. Although largely forgotten today, he was in his own time a respected member of the scientific community.

Digby is best remembered, today, for two things, his paper on the powder of sympathy, which I dealt with above, and his cookbook, to which I will now return. The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kt. Opened was first published posthumously by one of his servants in 1669 and has gone through numerous editions down to the present day, where it is regarded as a very important text on Early Modern food history. However, this was only one part of his voluminous recipe collection. Two other parts were also published posthumously. Choice and experimental receipts in physick and chirugery was first published in 1668 and went through numerous editions and translation by 1700, and A choice collection of rare chymical secrets and experiments in philosophy first published in 1682, which also saw many editions. What we have here is not three separate recipe collections covering respectively nutrition, medicine, and alchemy but three elements of a related recipe spectrum. We find a similar convolute in the work of Katherine Jones, Viscountess Ranelagh (1615–1691), Robert Boyle’s sister, an alchemist/chemist in her own right and an acquaintance of Digby’s.

There is little doubt in my mind that Sir Kenelm Digby Kt. was one of the most fascinating figures of the seventeenth century, a century rich in fascinating figures.

As was also believed when he died on his birthday in 1665, his epitaph read

‘Under this Tomb the Matchless Digby lies;

Digby the Great, the Valiant, and the Wise:

The Ages Wonder for His Nobel Parts;

Skill’d in Six Tongues, and Learn’d in All the Arts.

Born on the Day He Dy’d, Th’Eleventh of June,

And that Day Bravely Fought at Scanderoun.

‘Tis Rare, that one and the same Day should be

His Day of Birth, of Death, and Victory.’