The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library is the rare book library and literary archive of the Yale University Library. Yesterday their Twitter account posted a tweet entitled Galileo: Siderius Nunc, which linked to a blog post from July 11, 2022, by Raymond Clemens, Curator, Early Books & Manuscripts.

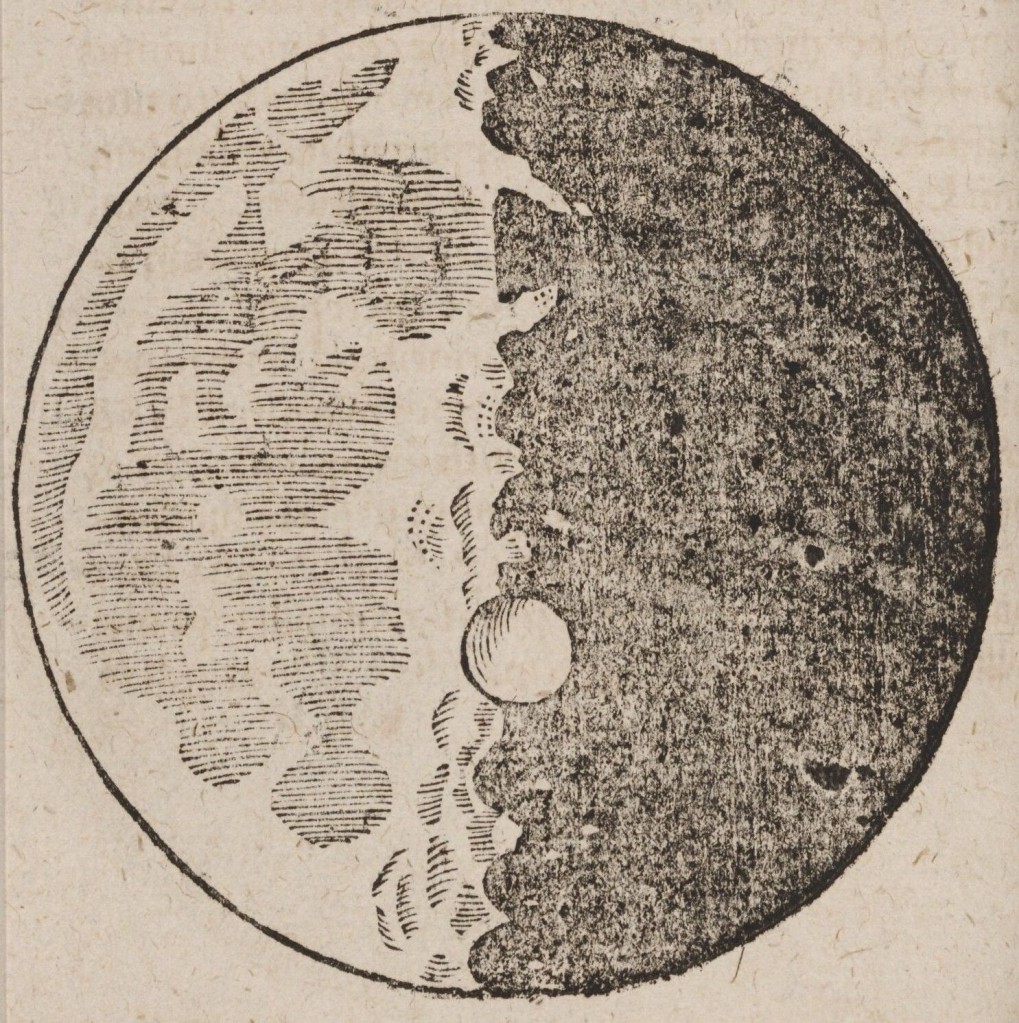

It featured one of Galileo’s famous washes of the Moon from his Sidereus Nuncius (1610) followed by a short text.

Our mini-exhibits end with the vitrine holding several copies of Galileo’s first printed images of the moon, the first ever made with the benefit of the telescope. For the first time, most Europeans were shown the dark side of the moon. Galileo’s sketches also emphasize its barren and rocky nature—well known to us today, but something of a revelation in the sixteenth century, when most people thought of the moon as another planet, thus generating its own light. Galileo was the first person to accurately depict the moons of Jupiter (which he called “Medicean stars,” after his patron, the Florentine Medici family). A photograph at the back of the vitrine was taken in 1968, before humans landed on the moon. It shows Earth as seen from the moon—the first time we saw our own planet from another astronomical body. This rough black and white image eerily resembles Galileo’s lunar landscape.

It is a mere 152 words long, not much room for errors, one might think, but one would be wrong.

We start with the heading. The title of Galileo’s book is Sidereus Nuncius and there one really shouldn’t shorten Nuncius to Nunc, as this actually changes the meaning from message or messenger to now! Also, it is Sidereus not Siderius!

In the first line Clemens writes: Galileo’s first printed images of the moon, the first ever made with the benefit of the telescope. I shall be generous and assume that with this ambiguous phrase he means first ever printed images made with the benefit of the telescope. If, however, he meant first ever images made with the benefit of the telescope, then he would be wrong as that honour goes Thomas Harriot.

The real hammer comes in the next sentence, where he writes:

For the first time, most Europeans were shown the dark side of the moon.

The first time I read this, I did a double take, could a curator of the Beinecke really have written something that mind bogglingly stupid? By definition the dark side of the moon is the side of the moon that can never be seen from the earth. The first images of it were made, not by Galileo in 1609, after all how could he, but by the Soviet Luna 3 space probe in 1959, 350 years later.

The problems don’t end here, he writes:

Galileo’s sketches also emphasize its barren and rocky nature—well known to us today, but something of a revelation in the sixteenth century, when most people thought of the moon as another planet, thus generating its own light.

In the geocentric system the moon was indeed regarded as one of the seven planets, but in the heliocentric system, which Galileo promoted, it had become a satellite of the earth and was no longer considered a planet. There was a long and complicated discussion throughout the history of astronomy as to whether the planets generated their own light or not. However, within Western astronomy there was a fairy clear consensus that the moon reflected sunlight rather than generating its own light. A brief sketch of the history of this knowledge starts with Anaxagoras (d. 428 BCE). The great Islamic polymath Ibn al-Haytham (965–1039) clearly promoted that the moon reflected sunlight. In the century before Galileo, Leonardo (1452–1519) in his moon studies clearly stated that the moon was illuminated by reflected sunlight. However, he never published.

Maybe, Clemens is confusing this with the first recognition of the true cause of earth shine, the faint light reflected from the earth that makes the whole moon visible during the first crescent, a recognition that is often falsely attributed to Galileo. However, here the laurels go to Leonardo but who, as always, didn’t publish. The first published correct account was made by Michael Mästlin (1550–1631)

Clemens’ next statement appears to me to be simply bizarre:

Galileo was the first person to accurately depict the moons of Jupiter (which he called “Medicean stars,” after his patron, the Florentine Medici family).

Galileo was the first to discover the moons of Jupiter, just one day ahead of Simon Marius, but to state that he accurately depicted them is somewhat more than an exaggeration. For Galileo and Marius, the moons of Jupiter were small points of light in the sky, the positions of which they recorded as ink dots on a piece of paper. To call this accurate depiction is a joke.

Somehow, I expect a higher standard of public information from the Beinecke Library, one of the world’s leading rare book depositories.