Long ago in another life, when I first became interested in, involved in, began learning, the history of science, the classic texts one was supposed to have read where all big books. Big theme books, big in scope and big in message. They covered deep periods of time and extensive areas of the evolution of a branch of science. All the big names had at least one big book and often more than one. Over time the big book went out of fashion, too general, too concentrated on big names and big events. They became replaced with close, detailed studies of one aspect of one corner of one discipline.

Over the years, the Welsh historian of science, Iwan Rhys Morus has written a series of detailed studies of various aspects of nineteenth-century British science, in particular detailing the history of electricity. 2005 saw When Physics Became King (University of Chicago Press), 2011, Shocking Bodies: Life, Death & Electricity in Victorian England (The history Press), 2017, Michael Faraday and the Electrical Century (Icon Books), also 2017, Willian Robert Grove: Victorian Gentleman of Science (University of Wales press, and most recently, 2019, Nikola Tesla and the Electric Future (Icon Books) (reviewed here), with a raft of papers to similar topics both in journals and collected volumes in between. Now he has written and published as big book and what a book it is, How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon: The Story of the 19th-Centuiry Innovators Who Forged Our Future[1], covering as it does a very wide range of science and technology throughout the nineteenth century, it is an absolute master class in how to write wide-ranging, big theme, narrative history.

Morus weaves internal history of science and technology together with the political, social, and cultural histories of science and technology into a single multidimensional, narrative strand that in not quite three hundred pages gives a densely packed, comprehensive overview of the development of the two disciplines in the nineteenth-century United Kingdom. A narrative that pulls the reader into that century and lets them breathe in the excitement and expectation that sparkles and crackles in the air generated by the future visionaries of Victorian Britain.

The book is structured chronologically on two different but interrelated levels. Each of the chapters, which are perhaps better described as sections, deals with a different aspect of the developments in the nineteenth century but taken together they describe an arc beginning in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries science wars between the old guard Baconian naturalists gathered around Sir Joseph Banks, a gentleman’s club that dominated the Royal Society, Britain’s leading scientific institution, on the one side and the younger generation of Cambridge University mathematical scientists led by Charles Babbage and John Herschel, who believed that science should be carried out by those with expertise and not those with social privilege. Travelling topic by topic through the century the arc closes with the advent of powered, heavier than air flight at the end of the nineteenth century, beginning of the twentieth century. However, within each topic there is a second chronological arc tracing the development of that topic from its early gleam in the eyes of its initial innovators through to its final fruition as a successful trendsetting, future defining technology.

The book opens with a science fiction vignette, describing the launch of the first British moon-landing mission in 1909 and closes with its successful return. Here Morus displays a quality of narrative writing that he maintains throughout the main text of the book, making it a pleasure to read, as well as both an entertaining and highly informative discourse.

Following the opening chapter with its description of the war between the Banksian gentlemen of science and the Cambridge mathematical men of science, Morus takes to another arena of conflict between the much-heralded engineers such as the Stephensons and Brunels, who shaped the infrastructure of the Victorian future with their railways, ships, bridges and tunnels, and the craftsmen who actually constructed those railway lines, tunnels, and bridges. Morus delivers here a fine demolition of the big names, big events style of historiography.

The third chapter illustrates the efforts to tame the new technology of electricity by fitting it with a solid quantified scientific corset. Defining the standards for the units of electrical potential, force and resistance and the laboratories and their researchers that grew out of those endeavours. Chapter four takes us into the wonderful world of the Victorian scientific and technological exhibitions in which innovators and inventors competed in their endeavours to persuade the general public and those in power to back their latest concepts designed to shape the future. Here we have everything from shop style exhibition spaces on the high street to the legendary spectacle that was the 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations held in the specially constructed Crystal Palace.

Chapter five is an object lesson in how quickly times change. It leads off with the euphoria that followed the introduction of the railways and how steam power was going to shape and revolutionise the future. A euphoria that was quickly pushed out of the way and replaced with exaltations for a future powered by the newest trend in energy, electricity. Both this and the previous chapter, on exhibitions, bring one of the book’s central themes to the fore, how the Victorians shaped their visions of the future based on emerging technology.

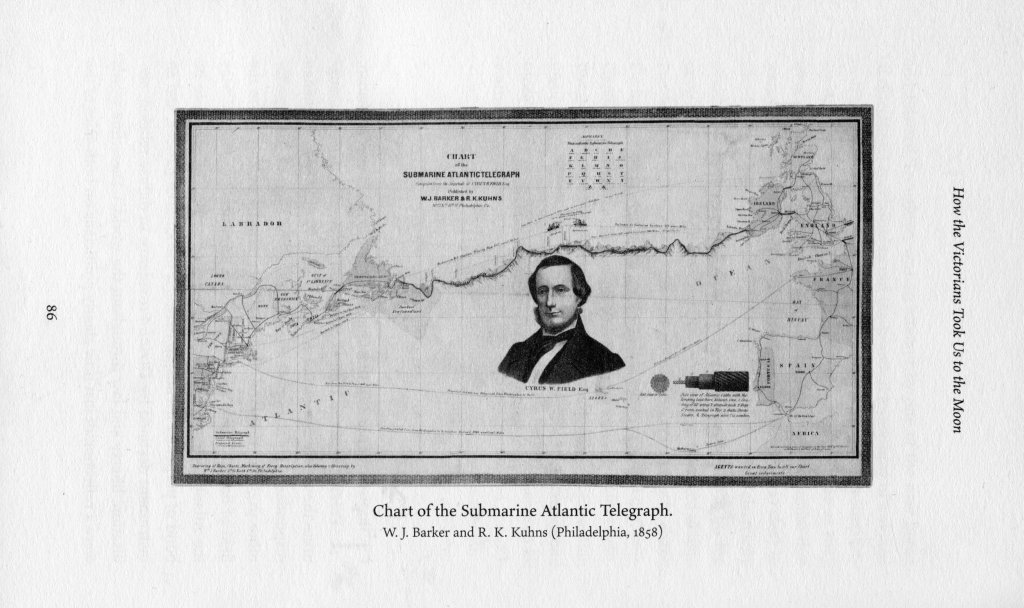

Chapter six deals with one of the great technological leaps of the nineteenth century, long distance communication. Electrical signals, first through wires, the telegraph and then the telephone and finally through the air with the wireless telegraph. Here another central theme of the book is emphasised the role played by the British Empire, in nineteenth-century Britain, in the production of new technologies, and in the marketing and exploitation. The Empire provided much of the raw materials needed to produce new technologies and a world-wide market where the inventors and innovators could maximise their profits. Technologies such as the telegraph and wireless telegraphy were, of course, useful tools to control and govern the Empire.

Another useful tool for those in control and governance that came into general use in the nineteenth century were the mechanical and later electro-mechanical calculators. Chapter seven, which deals with those development, features one of my personal favourite Victorians, Charles Babbage, who had major vision for his computing machines, vision that would only be truly realised in our own computer age. However, the slightly simpler calculating machines provided the politicians with a tool to develop the realm of social statistics and plan for the future.

As, stated earlier, the closing chapter deals with the history of manned flight. It was only in 1783 that the world saw the advent of unmanned and manned flights with both hot air and hydrogen balloons. The nineteenth century saw attempts to first power and steer balloons, rather than just letting them drift on the whims of the wind and then latter the development of the heavier than air aeroplane, including early plans to build steam powered flying machines.

The book closes with an epilogue that opens with the account of the return of the successful British moon landing expedition that opened the book. Morus then poses the question, whether the Victorians really could have staged a Moon landing? The answer is of course no, but is it? As Morus tells us:

In that sense, at least, the Victorians really did take us to the Moon. When Apollo 11 took off from the Kennedy Space Center on 16 July 1969 – just 60 years after the scene imagined after the scene imagined at the beginning of this book – and when the Eagle landed on the lunar surface on 20 July, it really was the culmination of a technological fantasy that began with the Victorians. What this book has tried to describe is the emergence during the course of the nineteenth century of new ways of thinking of thinking about and organising science that were directed at the future in a wholly new and unprecedented way, and some of the consequences of that reorientation. It is, by and large, the way we think about and organise science now, and the book is also an invitation to think what it means that we still do things the Victorian.

Page 287

This paragraph summarises Morus’ book far better than I ever could in fact the entire epilogue is a better review of the book than the one that I’ve written. Maybe I should just have scanned and posted it instead.

The book is well illustrated with the now ubiquitous grayscale picture, which Victorian media delivers lots of. There are extensive end notes listing the sources used but, as has become quite common in recent years, there is no separate bibliography. The book closes with an excellent index.

The title of this blog post reveals quite clearly what I think about this book but I’m now going to double down on it. Morus is a truly excellent writer and he has obviously invested much effort and thought in producing this jewel of a book. I have grown old and now read very slowly but I have had my nose stuck in a book since I was three years old and have over the decades read literally hundred of tomes. From time to time in my perusal of the world’s literature I have stumbled across a book that has left the deepest of impression on me. Such volumes are rare and with Iwan Morus’ latest publication I have added a new one to that brief list. If you study nineteenth century British history this book should be obligatory. As a case study for historians of science and/or technology it should probably also be obligatory. If you just like reading accessible, good quality, well written history books then you will love this one, so just acquire a copy and enjoy.

[1] Iwan Rhys Morus, How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon: The Story of the 19th-Centuiry Innovators Who Forged Our Future, Icon Books, London, 2022