The legendary soul singer, James Brown, was often referred to as “the Hardest Working Man in Show Business.” In analogy, one could refer to Philip Ball as “the Hardest Working Man in Science Communication.” He churns out books at a higher rate than most other science writers articles, as well as a constant stream of articles for a range of journals. On top of the flood of print on paper he also writes, produces, and presents an excellent radio broadcast for BBC Radio 4, called Science Stories; it’s well worth a listen if you don’t already. I have a running gag on Twitter that the work is actually done by a team of gnomes chained to their desks in the cellars of Ball mansions. As we follow each other on Twitter I finally managed to con him into sending me one of his books to be reviewed here at the Renaissance Mathematicus.[1]

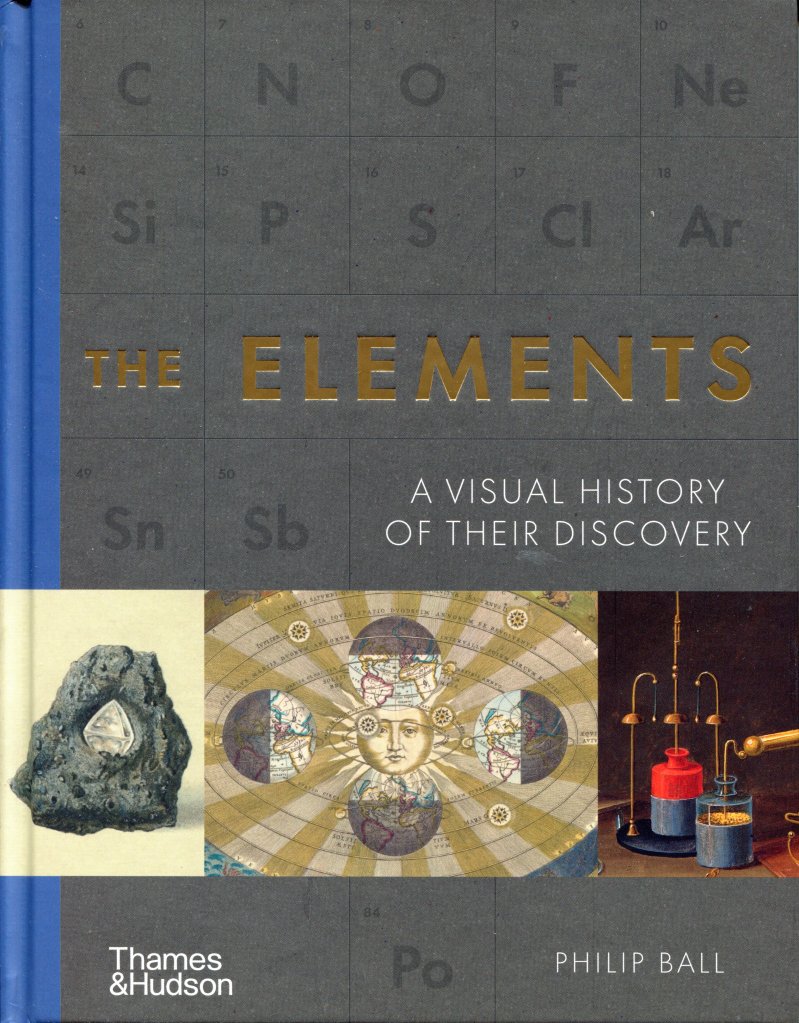

The book in question is The Elements: A Visual History of Their Discovery[2], it’s actually from 2021, as the publishers kept on ignoring Phil’s request that they should send me a review copy, but I kept reminding Phil and he kept prodding the publishers and persistence won out in the end.

The visual history is to be taken literally, it is a large format book chock full of incredible colour and sepia illustration with accompanying text. It is what is also sometimes, somewhat deprecatingly, referred to as a coffee table book, but despite the format and the visual emphasis this is a high value, easy access volume of absolutely first class, popular history of science.

The money quote in Ball’s introduction is:

All this implies that charting the history of the discovery of the chemical elements is more than an account of the development of chemistry as a science. It also offers us a view of how we have come to understand the natural world, including our own constitution. Furthermore, it shows how this knowledge has accompanied the evolution of our technologies and crafts – and ‘accompany’ is the right word to use, because this narrative challenges the common but inaccurate view that science always moves from discovery to application. Often it the reverse: practical concerns (such as mining or manufacture) generate questions and challenges that lead to fresh discoveries.

The book wonderfully illustrates all that is stated and implied in these few sentences.

Before I look at the book in more detail, one last general comment. The book consists of a large number of short, compact, stand-alone essays. Each one of these covers a single topic in at most a few pages. A lot of them are only two or three pages long and I think the longest only run to five pages. It should be noted that a large percentage of those pages are also taken up by the lavish illustrations. However, Ball is an absolute master of the short essay form. He manages, in each case, to include all of the relevant, cultural, historical, and scientific information necessary for a clear understanding of the topic at hand in a style that is easy to read and comprehend, even for the previously, completely uninformed reader. Believe me, as the author of a blog, I know how difficult that is.

As one might expect, given the subject, the book opens with a multi-coloured double page spread, periodic table. Each article on an element or group of elements has a small schematic periodic table at the top of a sidebar that shows their position in the periodic table. This sidebar also, to quote the author:

…show their atomic number, atomic symbol, atomic weight, periodic group name and number, and in some cases their phase at standard temperature and pressure (solid, liquid or gas)

Although the book opens with the periodic table, we don’t jump straight in with the modern chemical elements, it is constructed chronologically, and the first chapter starts with a general essay on the four classical elements, earth, water, fire, air. This is followed by one on the various ancient Greek philosophical matter theories before we plunge into individual essays on those four elements. This is followed by an excellent introduction to the Chinese five element system. We now go in search of the atom and having found it investigate the aether, the fifth element or quintessence, which closes out the first chapter.

Chapter Two introduces us to the metal of antiquity. After an introductory essay, we have the precious metals, gold, silver, and copper, followed by an essay on tin and lead and the chapter closes with a comparatively long one on iron, in many senses one of the most important materials discovered and exploited by humanity.

Chapter Three takes us into the world of the alchemist with the same schema, first an introduction then essays on sulphur, phosphorus, and antimony. Up next is a discourse on a substance that never existed but proved incredibly productive in the history of chemistry, phlogiston. The chapter closes with the question, “What exactly is an element?” answered with a presentation of the thoughts of Robert Boyle, a practicing alchemist, who is considered to have given the first halfway modern answer to the question.

Chapter Four delivers up the new metals, nine in total, leading us into Chapter Five and chemistry’s golden age. We have the gasses, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, followed by carbon. Once again, we have a substance that never existed but formed the basis for much experimentation, calorific. Just as phlogiston was considered to be substance given off by burning, so calorific was thought to be the elemental form of heat. The elements now come thick and fast, the halogens, chromium and cadmium, the sixteen rare earth elements. The chapter closes with John Dalton and the beginnings of the modern atomic theory.

Electricity enters the scene in Chapter Six and with it the elements discovered using it by chemists such as Humphry Davy: potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium, barium, strontium, boron, aluminium, silicon, and zirconium. The book opens with the periodic table known. I think, to all of us from the classroom wall, now we get introduced to the man, who is credited with having discovered it, Dmitri Mendeleev, although Ball also credits those who laid the trail to its discovery before Mendeleev.

I’ve already described the sidebars on the element essays, on the introductory essays the sidebars have a continuous chronic of the histories of science and technology interspersed with general historical events. In Chapter Seven, The Radiant Age, this chronic starts with the first transatlantic telegraph communication in 1858 and ends with the Russian Revolution in 1917. We have entered the realm of modern physics, electromagnetism, radiation, James Clerk Maxwell, Wilhelm Röntgen, Henri Becquerel, Marie and Pierre Curie, and many more. Following the introductory essay, we have caesium and rubidium with an introduction to spectroscopy, thallium and indium, helium, the inert gases, and to close radium and polonium.

The final chapter takes us into the nuclear age the chronic running from Albert Einstein in 1905 to the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. We fill a gap with technetium and extend the table with neptunium and plutonium, the accelerator elements–americium, curium, berkelium, californium–with claims and counter claims as to who created them first and thus won the right to name them. The bomb-test deliver up einsteinium and fermium. We have eight early trans-fermium elements, from atomic number 101 to 108, and the proofs of their existence gets harder. We enter the realm of less than a teaspoon full, and does it really exist with elements 109 to 118.

The book closes with a ‘sources for quotes’, or as they are known hanging endnotes to which there are no references in the text, as it is not an academic book, not so bad. There is then a very brief but very good list for further reading, followed by a very extensive picture credits list. It ends with a usable index.

All in all, Philip Ball is to be congratulated on an excellent, accessible, entertaining, and educational tome and I wish I could say that it is as near perfect as a commercial history of science book can be, but I can’t. The book has a serious blemish, a lacuna that I simply can’t ignore. I will introduce it with a couple of quotes from the book:

Paracelsus broadened this ‘unified theory of metals’ to include all substances, by adding a third principle, salt. He argued that mercury was the principle that made things fluid, salt gave them ‘body’ and made them solid. While sulphur was the principle of flammability: it made things burn. (page, 56)

First the German alchemist Johann Joachim Becher modified the Paracelsian scheme in claiming that there were three types of ‘earth’: a fluid sort (like mercury), a solid sort (like salt), and a fatty and combustible sort (like sulphur). (page, 66)

In ancient times, philosophers and craftspeople recognised seven different metals: gold, silver, mercury, copper, iron, tin and lead. This was a neat scheme, because each of the metals could be assigned a heavenly body: the Sun, Moon, and the five known planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Why do that, though? Because many natural philosophers believed that nature was governed by ‘correspondences’ like this between different classes of things. (page, 78)

Remember Chapter Two, The Antique Metals? We had gold, silver, and copper, followed by tin and lead, and then came iron, where was mercury? When I first realised that there was no entry for mercury, I couldn’t believe it and searched the book from beginning to end thinking I must have somehow overlooked it, but no, there is no entry for mercury. Still not believing my eyes I contacted Phil Ball and discretely inquired whether it was really so that he had forgotten, left out, mercury. His reply was an expletive, that I won’t repeat here. This has got to be the biggest copyediting error that I’ve ever encountered in a book. Phil says he will correct it in the paperback edition. At least he didn’t blame the gnomes.

Despite the absence of mercury, I whole heartedly recommend this wonderful book to just about everybody. In particular I think every home with children should own a copy, not stowed away on a bookshelf but laying around, on a coffee table for example, where inquiring minds could from time-to-time dip in and out of its beautifully illustrated and informative pages. It is a book that lends itself perfectly to dipping.

One small improvement that I would recommend, apart from an essay on mercury, is that each copy should come with a CD with Tom Lehrer’s The Elements.

[1] Actually, he was quite happy to do so, even the threat of a mauling by the HISTSCI_HULK didn’t stop him from doing so.

[2] Philip Ball, The Elements: A Visual History of Their Discovery, Thames and Hudson, London, 2021