One jab can safely sterilise domestic cats, a study has shown. The gene therapy approach could one day be used to control populations of feral cats.

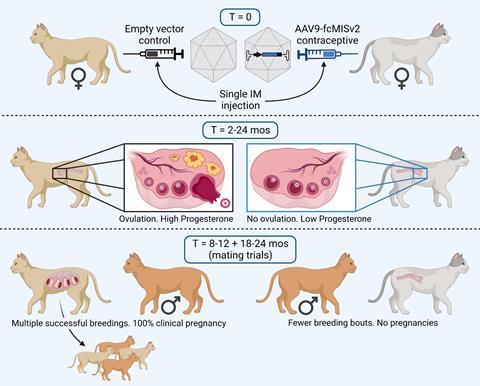

The gene therapy jab offers an easier, safer and cheaper alternative to spaying, which involves surgically removing the ovaries of female cats. The new therapy introduces an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector that ferries a gene for a cat hormone into the animal’s cells. The gene then becomes active inside cells, manufacturing anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH). This circulates in the animal, reaching the ovaries, where it blocks the maturation of oocytes or eggs.

AMH is a hormone made by multiple growing follicles inside the ovaries. As more of this hormone is produced, it signals to smaller follicles to suppress their growth and activation.

The virus chosen, AAV9, is particularly well adapted to infecting muscle cells. This is useful because muscle cells repair themselves via fusion and do not divide, which allows the hormone to be expressed for years.

‘Muscle cells producing the hormones do so in a steady fashion for – we hope – the lifetime of the animal,’ says David Pépin at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, who led the research. Contraception was successful for two years in six cats, but the group has followed the cats for four years now and their hormone levels should still prevent reproduction.

None of the six cats receiving the gene therapy became pregnant and four of them rebuffed all attempts by two tomcats to mate during two mating trials. Three control cats mated quickly, which in cats induces ovulation, and all produced litters of kittens.

‘The aim is to develop a permanent contraception,’ Pépin confirms. His research is funded in part by the Michelson Found Animals Foundation, an animal welfare charity that aims to develop nonsurgical sterilisation for free-roaming cats and dogs.

Spaying female cats is a procedure that requires anesthesia, surgery and a vet. ‘Paying for surgical procedures is very challenging for animal charities,’ says Cheryl Asa, former director of research at Saint Louis Zoo and expert in wildlife fertility control. ‘And is even more dire when dealing with feral or stray cat colonies.’ Mostly, this is dealt with by spaying, or neutering tomcats, which carries risks and is cumbersome, she adds.

AMH is highly conserved in mammals and the Pépin lab previously reported the successful sterilisation of rodents using this gene therapy approach. ‘There’s a high likelihood that this method would work in other species, particularly mammals, and we have early ongoing studies in dogs,’ says Pépin. ‘The concept may have use cases for invasive species.’

Another upside is that the cats continued to produce normal levels of reproductive hormones and showed no other behavioral changes.

The next step is a larger drug agency-approved trial in cats to demonstrate contraception. Ultimately, the aim would be to trap young, feral cats, give them a jab and then release them. ‘It’s always good to catch those cats anyway to give them their rabies vaccine,’ says Philippe Godin, a vet in Pepin’s lab.

‘Having an injectable, one-shot treatment that would induce long-term, even permanent infertility would be a godsend for people managing feral cats and running shelters,’ says Asa. ‘It would also benefit pet owners, who would rather not have their animal undergo surgery.’

One issue, though, is the price of the jab. ‘The cost of the gene therapy we see in humans is very high,’ admits Pépin, ‘but generally this has to do with the fact that it is for rare diseases and you’re treating dozens or hundreds of patients.’ This means pharmaceutical companies charge high fees to recoup the cost of research. Consequently, manufacturing capacity for millions of doses doesn’t exist.

‘We believe as more treatments are approved, and the capacity to produce viruses improves, then we can bring the cost down [for sterilising cats] to something as competitive, if not cheaper, than surgery.’