I have gained a reputation for pointing out and demolishing myths in the history of science. One area where these are particularly prevalent is in the history of the European Middle Ages. With numerous people claiming that there was little or no science during this period and what there was, was all wrong, usually blaming this situation on the Catholic Church. The people making these claims completely ignore the quite extensive literature on the history of medieval science written by such excellent historians as David C Lindberg, Edward Grant, Stephen C McCluskey, Bruce S Eastwood, Alastair C Crombie, and John E Murdoch amongst others. For those who don’t wish to plough through the academic literature, there is also a selection of excellent popular books on the subject, which I can warmly recommend. For example, David C Lindberg, The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450, (Chicago UP, 2nd ed. 2007), or perhaps Seb Falk, The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science(Norton, 2020), which I reviewed here. Finally, James Hannam, God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science, (Icon Books, 2009).

One of the most persistent myths against which my friend the HISTSCI_HULK has rampaged on several occasions is that, during the European Middle Ages, people believed that the world was flat. Following up on his excellent God’s Philosophers, James Hannam has now delivered the book that should squash that myth for ever, but I fear won’t, The Globe: How the Earth Became Round.[1]

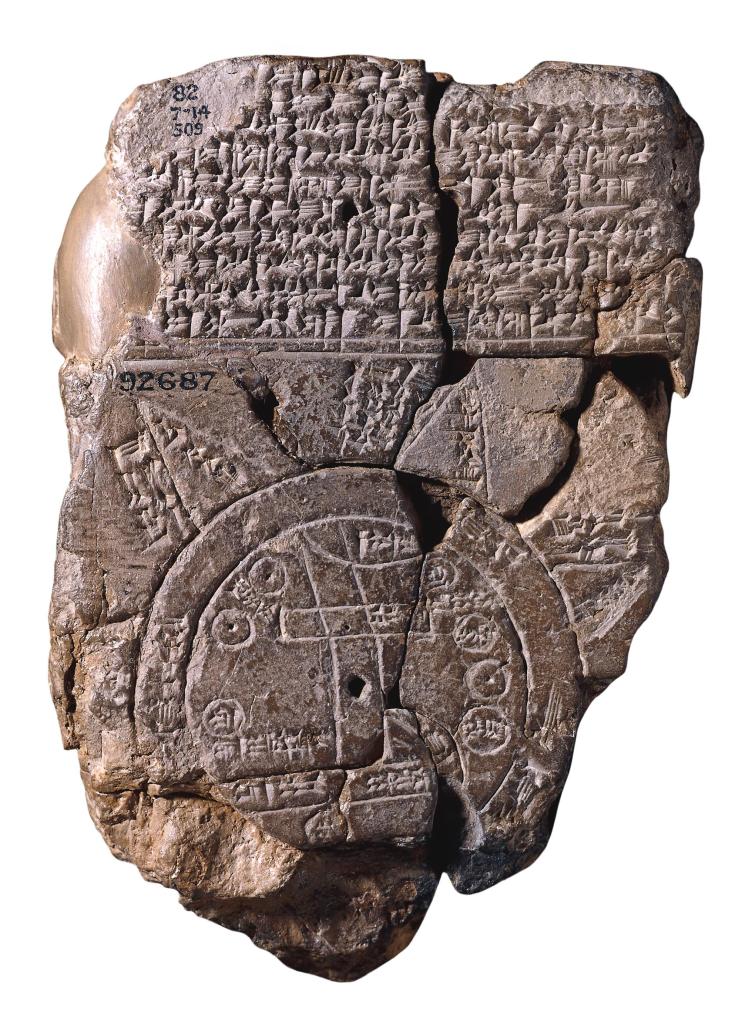

The blog post title is not just a piss poor play on words of the book’s subtitle, in his just over three-hundred pages, Hannam takes his readers on a journey both chronological and geographically around the world starting around 3000 BCE in the fertile crescent to England in the twentieth century on a wild zig zag course. The opening three chapters give brief but informative accounts of the image of the heavens and the earth of the ancient Babylonians, the ancient Egyptians, and the ancient Persians, all of whom believed in a flat earth with themselves at the centre under a ceiling like heaven, with varying explanations as to where the sun went at night and the moon during the day.

Having only devoted one brief chapter to each of these great ancient civilisations, Hannam now devotes six chapters to Ancient Greece! Seems unfair but it is here that the main action takes place, over a period of about four centuries the Earth transitioned from flat to spherical in Greek thought and Hannam, here, details each phase of that transition. He proceeds from Archaic Greece, the poems of Homer and Hesiod describing a circular flat earth, moving on to the Origins of Greek Thought, where he is refreshingly sceptical about claims made about Thales’ views. Next up are the Pre-Socratics and Socrates ending with Socrates death. Socrates is, of course followed by Plato and the earliest confirmed mention of a spherical Earth, Plato, in his Phaedo dialogue, supposedly quoting Socrates:

“I assumed that [Anaxagoras] would begin by informing us whether the Earth is flat or round, and then he’d explain why it had to be that way because that was what was better.”[2]

The following chapter on Plato goes deep into the discussion, as to where and from whom the idea that the Earth is a sphere first comes from, as it is obvious from the way that Plato writes about it that the discussion flat or round was already under way. After Plato comes Aristotle and we have the first clear statement that the Earth is a sphere, why it must be a sphere and empirical evidence that supports the statement that the Earth is a sphere:

Aristotle concluded his discission by showing how the theory of the Globe explained observations that might seem otherwise inexplicable. In the first place, he said that when there is a lunar eclipse the shadow of the Earth on the Moon is always curved. This corroborates what he had already shown from his first principles. The umbra during a lunar eclipse follows from the shape of the Earth. If it is a ball, its shadow must always be an arc.

His second piece of empirical evidence is the way the visible stars change as we travel north or south. He noted that some stars, which are visible in Egypt and Cyprus, can’t be seen in the north. He is almost certainly referring to Eudoxus’ observations of Canopus. It is bright enough to be hard to miss in Egypt, albeit usually low in the sky. Its absence from view in Athens would have been obvious to anyone who had seen it further south. This is only explicable if the Earth is rounded, if it were a flat plane, everyone would see the same stars. Since it is spherical, it’s inevitable that our view of the heavens will change with latitude.[3]

So, we have reached our objective, Aristotle demonstrated that the Earth is a sphere and not flat. End of story! No! Everything up till now was merely a prelude, the real story is just beginning. Hannam closes his section on Aristotle with the following:

By any conventional standards he [Aristotle] knew the Earth was a sphere, and he was probably the first person who did. On that basis, he discovered the theory of the Globe. As we will see in the remainder of this book, everyone today who knows the Earth is round indirectly learnt it from Aristotle. This makes the Globe the greatest scientific achievement of antiquity. It’s only because we take it as obvious that we don’t give Aristotle the credit he deserves.[4]

Hannam now take his readers of a journey through history and around the globe explaining how different cultures reacted when confronted, either directly or indirectly, with Aristotle’s truth. What their own vision of the Earth’s form was before that confrontation. Who came to accept the new vision, who reacted against it, rejecting. It’s a complex story that Hannam handles with verve, explicating clearly and accurately every twist and turn.

First off, Hannam stays with the Greeks and explains how the Stoics, who succeeded Aristotle as philosophical flavour of the century by supporting his conviction that the Earth was a sphere spread and established the view not only amongst the Greek but also the Romans, many leading figures having adopted the Stoic philosophy. The Stoics main rivals, the Epicureans, however, having adopted the cosmological theories of the Atomists reject the sphere maintaining that the Earth was flat. Their rejection of the sphere followed from their belief that the Earth was not the centre of the cosmos, the starting point of Aristotle’s argument for the sphere. Hannam also takes a close look at Greek cartography, if the Earth is a sphere how do you represent in in a flat diagram? Hannam moves on to a discussion of Roman culture and the representation of the Orbis within that culture.

In these sections Hannam points out that the Greek and Roman terms, such as the Latin Orbis, can mean both circle and sphere. Orbis is etymologically the origin of both orbit, a circle, and orb, a sphere. So, a modicum of caution is required when interpreting the historical texts.

Our journey now takes us through India, the Sassanian Persian Empire, Early Judaism and with it for the first time the Biblical view of the shape of the Earth and on into Christianity. Christianity had of course a problem with the inherent contradiction between the Bible, the infallible word of God, and the words of Aristotle. This led to a spirited discussion in the early Church that Hannam explicates, with his usual clarity. There was not just one but multiple discussion in the various early Christian communities. He we get one of the most notorious flat earther from antiquity, Cosmas Indicopleutes, who often gets quoted by those claiming that the people in the Middle Ages believed the world to be flat. The last of the so-called Abrahamic religions, Islam, comes next. With once again multiple discussion in particular about the discrepancy between the Koran and Aristotle. We had early Judaism now we have later Judaism in particular Moses Maimonides.

Europe in the Early Middle Ages is our next port of call. Mostly Aristotelian, most notably Augustine, but with exceptions most notably Lactantius, who would later feature in Copernicus’ De revolutionibus. Of interest here is Isidore of Seville (c.560-636) one of the most important encyclopaedists from late antiquity, who is in his writing more that ambiguous abut the shape of the Earth. Hannam argues fairly convincingly that, although he accepted Ptolemy’s astronomy and cosmology, he was a flat earther. However, Jürgen Hamel in his Die Vorstellung von der Kugelgestalt der Erde in europäischen Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts – dargestellt nach den Quellen,[5] (an excellent book if you can read German) agues equally convincingly that he wasn’t. I guess with Isidore, you pays your money and makes your choice.

Moving on to the next chapter, High Medieval Views of the World: ‘The Earth has the shape of a globe’, we are well into the territory of those promoting the myth that people in the Middle Ages believed that the Earth was flat; a myth that Hannam proceeds to demolish with style. The money quote is:

Take the coronation orb, which has been part of the regalia presented to kings and emperors from late antiquity. The orb represents the Earth, while the cross on top symbolises that the secular power was subject to the will of God. Presumably, if people in the Middle Ages had thought the Earth was flat, they would have presented their rulers with a diner plate instead.[6]

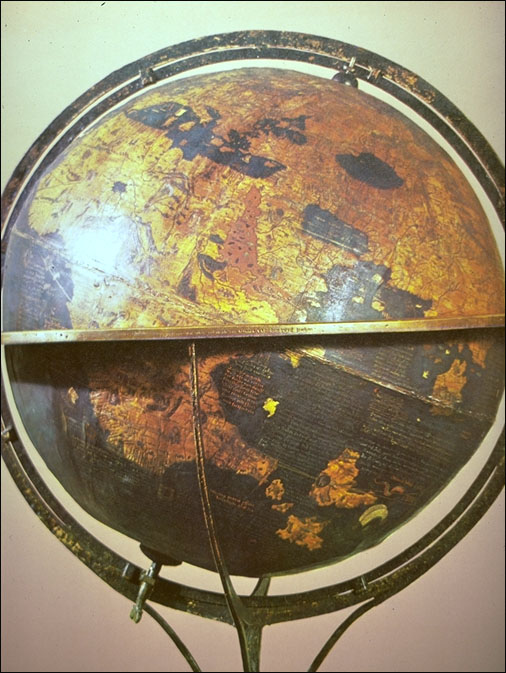

We move into the Early Modern Period with Columbus and Copernicus: ‘New worlds will be found,’ where Hannam also demolishes the myth that people thought Columbus would fall of the edge of the world and the equally stupid myth that Columbus proved that the world was round. We get a brief guest appearance of the world’s oldest surveying terrestrial globe, Martin Behaim’s Erdapfel (1492-94).

Columbus is followed naturally by Magellan and the first circumnavigation. The chapter closes with a brief look at what Copernicus has to say about the shape of the Earth and also why he said it.

China’s tradition view of the Earth and its reaction to the idea that it is actually a globe is a difficult and complex story, stretching over two chapters, which Hannam manages to relate with his usually sureness and style.

Moving into the modern period brief nods at the attempts to measure the size of the globe and the problems of determining longitude lead into the eighteenth-century dispute over the actual shape of the Earth, Newton & Huygens vs the Cassinis, oblate spheroid or prolate spheroid and the only part of Hannam’s entire narrative that I think is slapdash and shoddy. This is one of the most important episodes in the history of geodesy that also had ramifications for the theory of gravity and led to an indirect proof of diurnal rotation. It deserves more that Hannam’s sloppy two paragraph account.

This penultimate chapter contains two further sections, the first are brief accounts of explorers and missionaries bringing the news of the spherical shape of the Earth to communities that still hadn’t received it and how they reacted. The second is a brief account of the origins of modern Flat-Earth supporters in the nineteenth century. The final chapter continues with the flat earthers of the twentieth century. For theses two sections Hannam’s primary source is Christine Garwood’s excellent Flat Earth: The History of an Infamous Idea,[7] which I highly recommend if you are interested in the topic. The chapter proceeds with brief accounts of Draper-White conflict thesis and then moves on to the modern fantasy authors C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Terry Pratchett, who all knew better but still placed their fantasy novels in flat earth medieval settings.

Hannam’s book has extensive endnotes that mostly refer to the equally extensive bibliography. The book also has an extensive index. The book is richly illustrated but in the proof copy I was supplied with to write this review they are unfortunately very poor quality grey scale reproductions. I can only assume that they are better in the published version of the book.

James Hannam’s book is truly first class and should become a standard work on the topic. He covers a very wide range of material in a comparatively small number of pages. Each section of the book is relatively brief but concise, historically accurate, and highly informative. He writes extremely well, and his prose is clear and light to read. Anybody who takes the trouble to read this book will at the end know when, where and how the various populations of the Earth became aware that their home was on a large sphere floating through space. A fact first truly recognised by Aristotle in the fourth century BCE and slowly disseminated around the globe over a period of more than two thousand years. Hannam has produce a first-class documentation of that dissemination.

[1] James Hannam, The Globe: How the Earth Became Round, Reaction Books, London, 2023

[2] Hannam p. 75

[3] Hannam p. 93

[4] Hannam p. 97

[5] Jürgen Hamel, Die Vorstellung von der Kugelgestalt der Erde in europäischen Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts – dargestellt nach den Quellen, Abhandlung zur Geschichte der Geowissenschaften und Religion/Umwelt-Forschung, Neue Folge, Band 3 pp. 51-52

[6] Hannam p. 227.

[7] Christine Garwood, Flat Earth: The History of an Infamous Idea, Thomas Dunne Books, NY, 2007