In the last episode I outlined those aspects of Aristotle’s philosophy that would go on to play a significant role of the history of physics in later centuries. Because Aristotelian philosophy came to play such a central role in medieval thought in the High Middle Ages, there is a strong tendency to think that it also dominated the philosophical scene throughout antiquity. However, this was not the case. Although his school, the Lyceum, survived his death in 332 BCE and under the leadership of Theophrastus (c. 371–c. 287 BCE) enjoyed a good reputation. Theophrastus produced some good science, but it was natural history–biology, botany–not physics as indeed the majority of Aristotle’s scientific work had been. After Theophrastus died the Lyceum went into decline. However, the school was in no way dominant, the main philosophy of Ancient Greek following Aristotle being Stoicism and Epicureanism. Both of these philosophical directions “shared the aim of attaining tranquillity or freedom from worry (ataraxia), yet their explanations of the world were often radically different, even opposed.”[1]

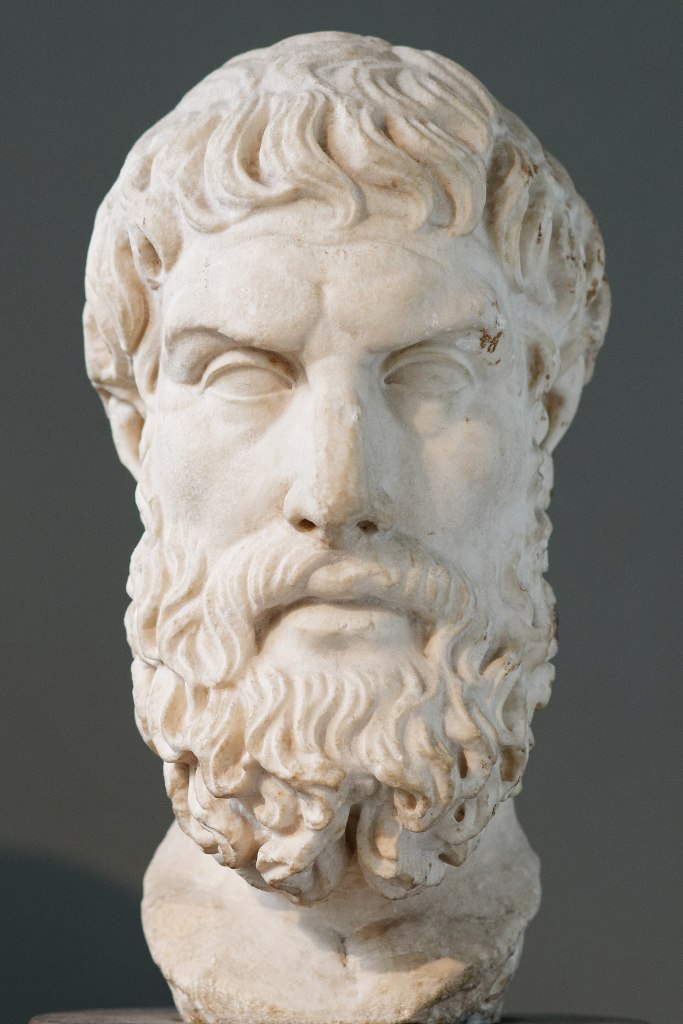

Epicurus (341–270) had a rather negative attitude towards natural philosophy:

Epicurus was content for his followers to have an ‘in principle’ approach to understanding the world. He explained that it is not necessary to become too caught up in details. In fact, he argues that less is more, because knowing less can prevent confusion and worry. In Epicurus’ view, there is a distinct possibility of being blinded by science, and this is to be avoided. While Epicurus indicates that he had himself worked out the details of his views more fully, he advocates that a summary is sufficient. A physical theory that can withstand objections and leads to peace of mind should be accepted.[2]

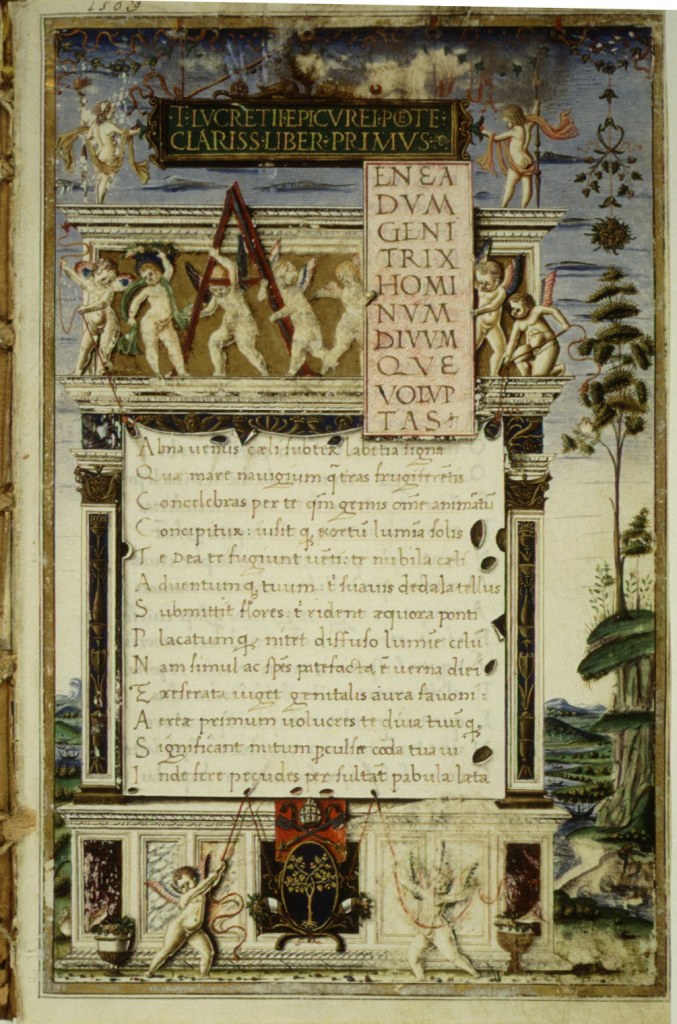

Epicurean natural philosophy was retrograde, it rejected the developments made by Empedocles, Plato, Eudoxus, and Aristotle and returned to the views of the Atomists. There existed only bodies and space and the bodies were composed of atoms. Because space, the void was infinite and had no centre they rejected Aristotle’s arguments for a spherical earth at the centre of a spherical cosmos and supported a flat earth floating in the void. As with so many of these figures, Epicurus supposedly wrote a large number of books of which only a few short works survive. However, the Roman poet and philosopher, Lucretius (c. 99–c. 55 BCE) presented the Epicurean philosophy and physical theory in his poem, De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things), This would go on to play a role in the introduction of a particle theory of matter in the Early Modern Period.

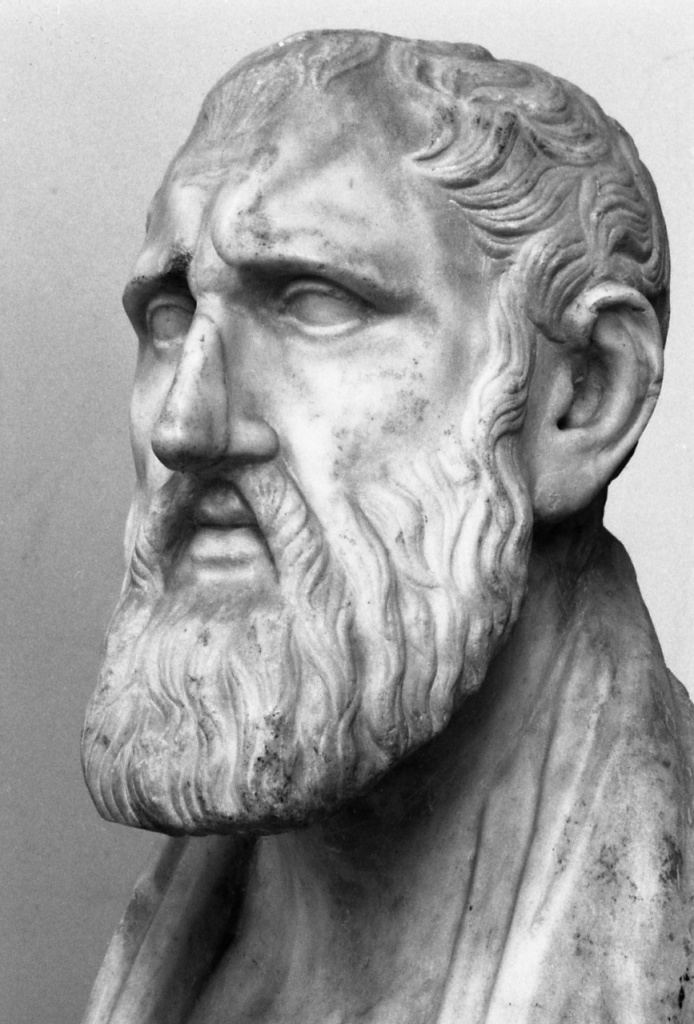

Unlike Epicureanism, Stoicism did not have a single direction determining founder, although Zeno of Citium (c. 334–c. 226) BCE, is regarded as the first Stoic.

He developed his ideas out of the philosophy of the Cynics being, for a time, a pupil of Crates of Thebes (c. 365–c. 285 BCE). However, equally important in the early phase of Stoicism were, Zeno’s pupil Cleanthes of Assos (c. 330–c. 230 BCE) and his pupil Chrysippus of Soli (C. 279–c. 206 BCE).

As with almost all major Greek philosophers in this period, according to hearsay, they all wrote lots of books but only fragments of their actual writings have survived. Most of the reports on what they actually believed and practiced come from writers active centuries after they lived. As opposed to Epicurus and Epicureanism, Stoic philosophy is thought to be the result of a collective of writers rather than one dominant individual.

The Stoic philosophy has three major pillars logic, physics (natural philosophy), and ethics. As this series is about the history of the evolution of physics I shall ignore the ethics, although it was the ethics that made, and still makes, Stoicism attractive to many people. The Stoics, like Aristotle, placed a strong emphasis on logic but whereas Aristotle laid his emphasis on logical deductive reasoning using the syllogism, which is a logic of classes, the Stoics are credited with developing the earliest European logic of proposition or predicative logic. This development is usually attributed to Chrysippus but we have little or nothing of his original texts and rely on later reports by Diogenes Laëtius (fl. 3rd century CE), Sextus Empiricus (2nd century CE), Galen (129–c. 216 CE), Aulus Gellius (c. 125–after 180 CE), Alexander of Aphrodisias (fl. 200 CE), and Cicero (106–43 BCE).

Stoic physic is interesting both for its similarities with and differences to Aristotle. Unlike Epicurus, the Stoics accepted the basic Platonic-Aristotelian model of the cosmos as a sphere with a spherical Earth at its centre. They were in fact mainly responsible for the acceptance of this model by the Roman. They also largely accepted the existing astronomical model of the planets revolving around the Earth on circular orbits. However, their cosmology had a major difference to that of Aristotle that would become highly significant when Stoicism was revived in the Early Modern Period.

The Stoics were pandeists, that is they believed that god was the cosmos and everything in it and the cosmos and everything in it was god. As a result, their matter theory was radically different to that of both Plato and Aristotle. To quote Wikipedia:

According to the Stoics, the Universe is a material reasoning substance (logos), which was divided into two classes: the active and the passive. The passive substance is matter, which “lies sluggish, a substance ready for any use, but sure to remain unemployed if no one sets it in motion.” The active substance is an intelligent aether or primordial fire (pneuma) which acts on the passive matter:

The universe itself is God and the universal outpouring of its soul; it is this same world’s guiding principle, operating in mind and reason, together with the common nature of things and the totality that embraces all existence; then the foreordained might and necessity of the future; then fire and the principle of aether; then those elements whose natural state is one of flux and transition, such as water, earth, and air; then the sun, the moon, the stars; and the universal existence in which all things are contained.

— Chrysippus, in Cicero, De Natura Deorum, i. 39

For their cosmology, a major consequence of this philosophy was that the Stoics rejected Aristotle’s division of the cosmos into the supralunar and sublunar spheres, they were both the same for the Stoics, and they considered comets, which as I said in the last episode played a major role in the emergence of modern astronomy, to be a supralunar phenomenon as opposed to Aristotle who regarded them as a meteorological or atmospheric phenomenon.

Both Epicureanism and Stoicism were very popular amongst educated Romans, such as Cicero and Seneca (c. 54 BCE–c. 39 CE), and the later Greek philosopher Plutarch (c. 46–119 BCE), who quoted and discussed Epicurean and Stoic philosophers in their writings. They remained so until about 300 CE when they in turn faded into the background and were replaced by the Neoplatonist. However, those writers who paid the most attention to them were those Latin stylists who were most popular amongst the Humanist philosophers of the Renaissance and so their ideas experienced a revival in the Early Modern Period and there had an impact on the evolution of science.

[1] Liba Taub, Ancient Greek and Roman Science: A Very Short Introduction, OUP, 2023 p.

[2] Taub p. 70