This year’s chemistry Nobel prize has been awarded jointly to nanotechnology pioneers, Moungi Bawendi, Louis Brus, and Alexei Ekimov for the discovery and synthesis of quantum dots. However, news of their win was leaked around two hours before the official announcement was made, in a press release sent out in error to a Swedish newspaper by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

When asked about the mistake, Hans Ellegren, secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, said it was ‘very unfortunate’ that the news was leaked. ‘We deeply regret what happened for sure, there was a press release sent out for still unknown reasons, we have been very active this morning to try to find out what happened but we don’t know … we deeply regret that it happened.’

Quantum dots are semiconducting crystals just a few nanometres wide. They are typically made from combinations of transition metals and/or metalloids – most commonly cadmium selenide and cadmium telluride – just like regular semiconductors.

Changing the size of a quantum dot changes its properties, in particular its fluorescence, meaning they can be tuned to produce different colours. The smaller the nanoparticle, the narrower the wavelength it emits – smaller dots emit blue light while larger ones emit red light.

In 1981, Ekimov a solid-state physicist working at the time at the Vavilov State Optical Institute in Russia, succeeded in creating size-dependent quantum effects in coloured glass. The colour came from nanoparticles of copper chloride and Ekimov demonstrated that the particle size affected the colour of the glass via quantum effects. This was the first time someone had succeeded in deliberately producing quantum dots.

A few years later, unaware of Ekimov’s study, Brus, a US chemist studying colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals at AT&T Bell Laboratories, became the first scientist to prove size-dependent quantum effects in particles floating freely in a solution. He too understood that he had observed a size-dependent quantum effect.

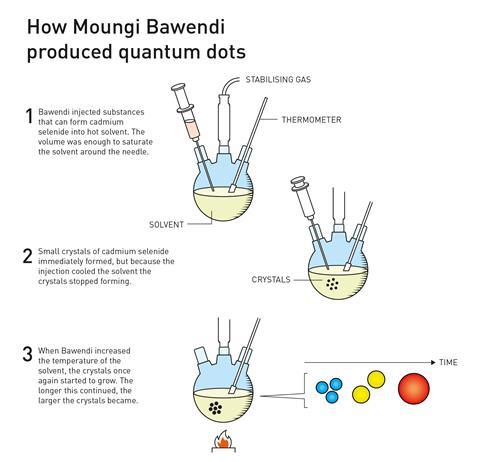

Continuing with efforts to produce higher quality nanoparticles, in 1993 Bawendi, a research leader at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US, had a major breakthrough when his group succeeded in growing nanocrystals of a specific size. He was credited with revolutionising the chemical production of quantum dots, resulting in almost perfect particles – an essential step for them to then be mass produced.

During the press conference, a phone call was made to Bawendi in which he described the win as ‘an honour’. ‘I was very surprised, sleepy, shocked, unexpected, but very honoured,’ he said.

Responding to questions from journalists about the win and the implications of his work he said: ‘It’s a field with a lot of people that have contributed to it from the beginning… I didn’t think that it would be me that would get this prize because we’re all working together on this.

‘This was a process, I think that the community, because it became a larger community, realised the implications in the mid-90s that there could potentially be some real-world applications.’

Now quantum dots are found in a wide range of commercial products, across scientific disciplines, from computer monitors and television screens based on QLED technology, to biomedical imaging.

‘Research is still very intense and there are applications expected or being heavily researched in producing photons for quantum communication, for flexible electronics for sensors for improving solar cells, making them better or cheaper … among many other things,’ said Heiner Kinke, member of the Nobel committee for chemistry during the prize press conference.

‘So for these reasons, the Nobel prize in chemistry for 2023 will be awarded for to Alexei Ekimov and Louis Brus for the discovery that it is possible to make such quantum dots, and Moungi Bawendi for a synthesis method that made quantum dots widely useful.’

Gill Reid, president of the Royal Society of Chemistry, said the recognition of this work on quantum dots was ‘really exciting’ as it showed how chemistry could be used to solve a range of challenges.

‘These remarkable nanoparticles have huge potential to create smaller, faster, smarter devices, increasing the efficiency of solar panels and the brilliance of your TV screen,’ she said.

‘Great science benefits from diverse viewpoints as part of a collective endeavour, and this year’s prize is a great example of that – people working in different labs, in different countries, approaching a problem from different angles. We don’t work in isolation in chemistry – teamwork is both a fundamentally important aspect of how science is actually done, and one of the most fun!’

David Pendlebury, head of research analysis at the Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate, which identified both Brus and Bawendi as Nobel-worthy in 2012 and 2020, respectively, said the researchers’ ‘incredible contributions to chemistry’ were reflected in their citation records. ‘Bawendi shows an astonishing 100,000+ citations in the Web of Science, and Brus 60,000+,’ he added.