I don’t remember ever coming across half a paragraph of just nineteen lines that manages to cram in so many history of science and technology myths, errors, and falsehoods as the one that I recently read whilst soaking in a hot bath. A truly monumental cluster fuck!

The offending object is on page 131 of David B. Teplow’s The Philosophy and Practice of Science[1], which I will be reviewing in the not to distant future and which is much better than the handful of lines dumped on here and which I will almost certainly be recommending but for now the cluster fuck.

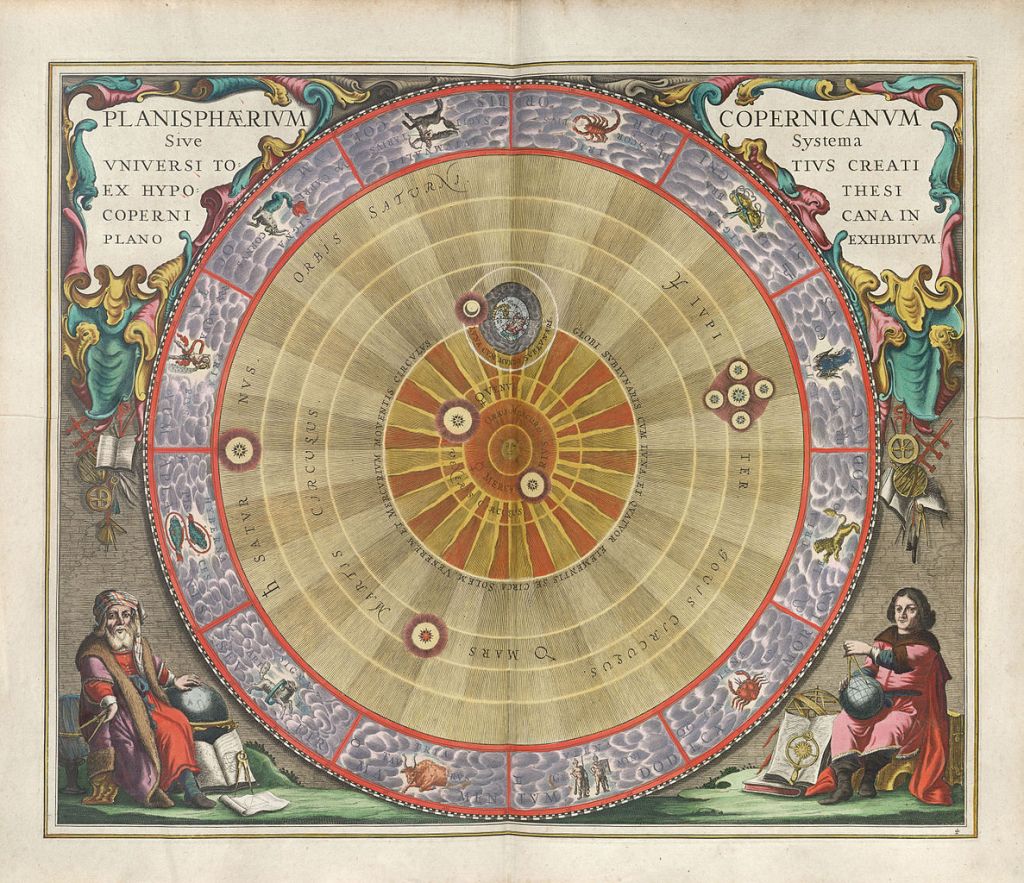

Revolutionary advance in science have been achieved through a number of mechanisms. Optics is a good example. Simple, but keen and thoughtful, observation of the worlds at a magnification of 1x, combined with logic, enabled Aristotle to lay the foundation for all of science and for Copernicus to propose a heliocentric solar system.

The statement about Aristotle laying the foundation for all science is definitely questionable given his rejection of mathematics but I’ll let it pass. Copernicus proposal of a heliocentric solar system was not in anyway based on observation but on rethinking elements of the existing geocentric system.

Galileo’s construction of the first telescope’s allowed him to observe the world at ≈30x and to confirm Copernicus’s theory of a heliocentric heavens.

Galileo by no means constructed the first telescopes. Apart from being preceded by the various inventors of the telescope such as Hans Lipperhey and Jacob Adriaenszoon, by the time he learnt about telescopes they were on sale all over Europe. The Venetian Senate was truly pissed off when they discovered this after giving Galileo a massive pay rise for presenting them with a telescope, having thought it was something very special. Galileo was also definitely preceded as a telescopic astronomical observer by Thomas Harriot and probably by Simon Marius. If I could get my hands on the idiot, who first perpetrated the myth that Galileo’s observations confirmed Copernicus’s theory of a heliocentric heavens, I would shove a Galilean telescope up his fundamental orifice. Galileo knew that nothing that he had observed confirmed Copernicus’s theory and he never claimed that he had. It would be 1725 before James Hadley produced the first telescopic observation that confirmed part of the heliocentric theory, when he observed stellar aberration.

It [optics] also enabled van Leeuwenhoek to study the microscopic world, at ≈250x, and in the process discover “animalcules” (from the Latin for “tiny animal”; animalculum) – including bacteria, protozoa, and spermatozoa – thus becoming the first microscopist and microbiologist.

Van Leeuwenhoek is a very long way from being the first microscopist. It’s actually difficult to establish who first began using microscopes as scientific instruments. Galileo knew of the microscope and almost certainly discovered the principle, as probably did many others, when looking through a Galilean or Dutch telescope ( one convex, one concave lens) the wrong way it, when it functions as a microscope, but he did make any systematic microscopic studies. The Dutch engineer, inventor, (al)chemist, optician, and showman Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel (1571–1631) was constructing and giving public demonstrations with Keplerian microscopes (two convex lenses) by about 1620. Galileo built a compound microscope in 1624, which he presented to Prince Federico Cesi founder of the Acccademia dei Lincei.

The first illustrations made with a microscope are attributed to Francesco Stelluti on a pamphlet published by the Acccademia dei Lincei to celebrate the election of Maffeo Barberini as Pope in 1623. The bees were the Barberini family emblem. Stelluti published further microscopic studies of bees in a Tuscan translation of an obscure Latin poem in 1630.

In 1644 Giovanni Battista Odierna published a pamphlet of his microscopic studies of the fly’s eye, his L’Occhio della mosca and in 1656 Pierre Borel published a collection a collection of a hundred miscellaneous microscope observations, his Observationum microscopicarum canturia.

The Italian biologist Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694) observed capillary structures in frog’s lungs with a microscope in 1661 putting him ahead of van Leeuwenhoek as microbiologist.

Given his propensity to vehemently claim priority on every aspect of his research in his polymathic career, Robert Hooke would almost certainly be enraged by our authors claim, as his magnificent and ground-breaking microscopic study the Micrographia was published in 1665, eight years before van Leeuwenhoek’ first letter was published by the Royal Society. Hooke would probably also claim priority as the first microbiologist for his study of and naming of biological cells.

The claims that van Leeuwenhoek was the first microscopist and microbiologist are total bullshit and display a level of ignorance and/or laziness, on Teplow’s part, who either didn’t bother to check his facts or to do the bloody research.

Electron and atomic force microscopes now allow scientists to see objects at magnifications up to ≈107x, opening up an immense sub-cellular world in which even individual atoms can be visualized. These instrumental advances expanded the observable universe, and the amount of information to which one has access, many orders of magnitude.

Nothing to complain about here.

The best example of a recent revolution in scientific method comes from computer science, a field that for all intents and purposes, did not even exist until the twentieth century.

Nor here, but the pain starts again in the very next sentence.

The development of mechanical computers (the “difference and analytical engines”) and arbitrary, user-defined programs (“weav[ing] algebraic patterns”) by Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, respectively, followed by the conception and development of electronic computers by John van [sic] Neumann and Alan Turing ushered us into the current “information age.”

Oh boy! Babbage’s Differential Engine, a special purpose computer designed to calculate and print error free mathematical tables using the method of differences was never realised, beyond a small working model, which he had his engineer Joseph Clement (1779–1844) construct in 1832, before the project was abandoned. The Analytical Engine, conceived as a grandiose multipurpose computer never got off the drawing board.

Although she described the concept of arbitrary, user-defined programs in her notes to her translation of Luigi Menabrea’s Notions sur la machine analytique de M. Charles Babbage (1842), the concept is from Babbage and not Lovelace. The full quote from Lovelace’s notes is “we may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.”

The idea of a machine that could transcend number, as the Analytical Engine had transcended addition and had been generalized to other operations, had been in Babbage’s thoughts for some years. In a letter to Mary Somerville written 12 July 1836, he spoke of having “a kind of vision of a developing machine.” This was only twelve days after he had taken the decision to adopt punched card as input to the Analytical Engine, and two days after he mused in his notebook.

This day I had for the first time a general but very indistinct conception of the possibility of making an engine work out algebraic developments – I mean without any reference to the value of the letters. My notion is that as the cards (Jacquards) of the calc. engine direct a series of operations and then recommence with the first, so it might be possible to cause the same cards to punch others equivalent to any given number of repetitions. But these hole[s] might perhaps be small pieces of formulae previously made by the first cards and possibly some mode might be found for arranging such detached parts according to powers of nine numbers and of collecting similar ones [the entry breaks off here].

What he was groping for here was some means of bypassing or replacing the columns of numbers that are ordinarily the objects to be operated on, so that he could operate on symbols instead.[2]

Note that this is eight years before Ada translated the Menabrea article. Note also, whereas Ada drops the suggestion in a simple, highly quotable, poetic bon mot, Babbage was acutely aware of the problems involved in actually achieving this aim. As I’ve sodding well said a hundred bleeding times, before accrediting anything to Countess Lovelace see what Babbage has said on the subject in his correspondence and unpublished papers.

One should also note that there was no continuity or influence between Babbage’s schemes and the invention of the computer in the twentieth century. It was only with hindsight that historians began to praise Babbage as a pioneer of the computer age.

Neither Alan Turing nor John von Neumann conceived or developed the effing computer! Vannevar Bush (differential analyser, 1927), Konrad Zuse (Z2 1940, Z3 1941), Vincent Atanasoff & Clifford Berry (ABC, 1942), Howard Aiken (Harvard Mark I, 1944), Tommy Flowers (Colossus, 1943–45), and John Mauchly & J. Presper Eckert (ENIAC, 1945) did conceive and develop computers.

In 1936 Alan Turing published a meta-mathematical paper, On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, which after other people had developed computers provided a succinct way of categorising the computing capabilities of a computing machine.

During WWII Turing, together with Gordon Welchman, developed the Bombe from the Polish Bomba, an electro-mechanical device used to help decipher German Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages. The Bombe was designed and constructed by Harold Keen. After WWII, Turing worked on the design of the Automatic Computer Engine (ACE), which he presented in 1945. The ACE was never built.

Beginning in 1944, ENIAC inventors, John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, designed the Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer (EDVAC) the machine being finally delivered in 1949. Brought in as a consultant, John von Neumann wrote a description of the EDVAC, First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC, which was published in 1945 and led to Mauchley and Eckert being denied a patent for EDVAC.

This totally lazy and factually incorrect Turing and von Neuman invented the computer that has become established in popular history of technology gets on my fucking wick. Teplow’s paragraph that I have dissected above is a glowing example of lazy, cliché filled, badly researched history of science and technology that should not be being published by a major academic publisher in 2023.

[1] David B. Teplow, The Philosophy and Practice of Science, CUP, 2023

[2] Dorothy Stein, Ada: A Life and a Legacy, The MIT Press, 1985. pp. 102–103