This is one of my occasional autobiographical posts, so if you come here just for the #histsci, you can skip this one.

I recently decided to be sensible and to relinquish my claim to a part of my inheritance, a drum. This is not just any drum, it is a very special drum and I’ve decided to tell its, for me, rather fascinating history. In order to tell the story of this drum I first have to sketch a large chunk of my family’s own somewhat atypical history.

My mother was born in Rangoon in Burma, then part of British India, as a, I think, third generation colonialist. She was born into a wealthy family and enjoyed a first-class education, for a woman of a certain standing. However, instead of finding a suitable husband and marrying, as would have been the normal course for a young lady in her position, she took up a career and became a SRN (State Registered Nurse), advancing eventually to matron of a hospital.

My father was born in London the son of a bank manager of Lowland Scots extraction. He attended a minor public school, where he excelled academically, and in the autumn of 1939 was due to go up to Oxford to study Greats, that’s Latin, Greek and Ancient History, for those not up on Oxbridge slang, considered in those days the pinnacle of the British education system.

However, this was not to be. On 1 September 1939, Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany. My father having received a full military training in his public school cadet corps, in which he was an officer, did not wait to be mustered but volunteered for military service. Because he not only spoke ancient Greek, but was also fluent in modern Greek, he also volunteered for oversees service. After all, Greece was also a theatre of war. The British Army in the grand tradition of large bureaucratic organisations sent my father, not to the Balkans, but to India, where he became an officer in the Royal Indian Army.

At some point during the war my father fell ill and ended up being treated in the hospital where my mother ruled the roost. In true romantic novel tradition, the dashing young British officer and the beautiful, dark haired colonial nurse fell in love and married. At the end of the war my father, now a major, was decommissioned and became a civil servant in the British colonial administration. My brother was born in 1945 in Lahore, which was then still in India but is now in Pakistan. In 1947, my eldest sister was born in the same hospital in Rangoon as my mother.

Come independence, my family had to leave India and came to Britain. My father was, of course, returning home but my mother, already over thirty, was coming to Europe for the first time in her life, as were my brother and sister. They moved to Whalley Bridge in Derbyshire, to a house my father had inherited from his mother.

Thanks to the support of a local politician and businessman, my father now attended the University of Manchester, where, his military service being credited as a BA, he did a MA in Egyptology. My second sister was born in Buxton in 1950. In the summer of 1951, my family moved to Thorpe-le-Soken, an agricultural village in North East Essex, and I was born in December of that year, In Clacton-on-bloody-Sea of all places. That stain remains in all my official documents for life!

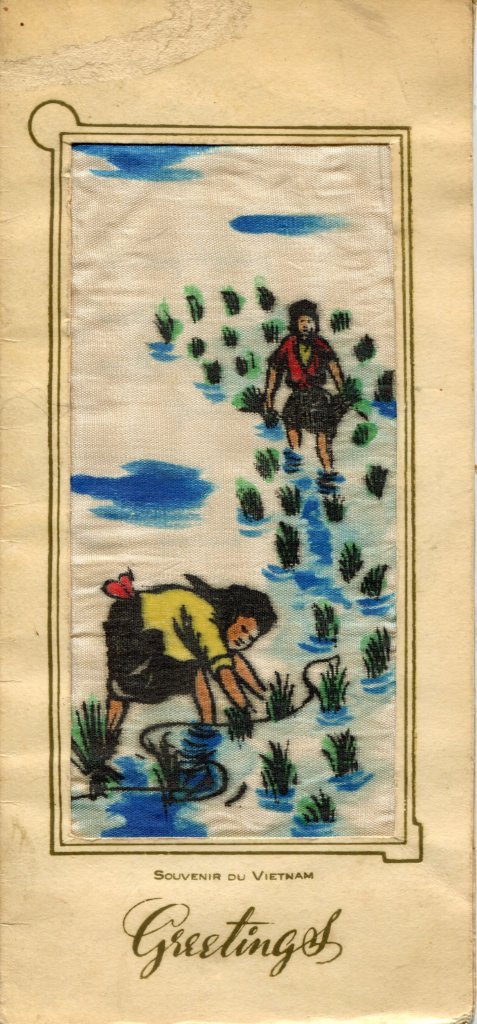

The move was motivated by my father’s appointment as lecturer for Art and Archaeology of South East Asia at SOAS in London. Quite how a man who had spent eight years living and working in India and then done as MA in Egyptology became a lecturer for Art and Archaeology of Southeast Asia is a puzzle that I still haven’t solved! Following the defeat of the French colonial government in Vietnam in 1954, my father spent a sabbatical year in SE Asia mostly in Vietnam. I still have a Vietnamese birthday card printed on silk that he sent me, but I no longer have the French Dinky Toy armoured car that also came from there.

Somewhere down the line my father became an expert for the Vietnamese, Bronze Age, Đông Sơn culture. Archaeologists define cultures by the artefacts that are typical for that given culture. Đông Sơn culture is define by its bronze artifacts, in particular the Đông Sơn drums.

The drums were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE; they are one of the culture’s most astounding examples of ancient metal working. The drums, cast in bronze using the lost-wax casting method are up to a meter in height and weigh up to 100 kilograms. Đông Sơn drums were apparently both musical instruments and objects of worship.

They are decorated with geometric patterns, scenes of daily life, agriculture, war, animals and birds, and boats. The latter alludes to the importance of trade to the culture in which they were made, and the drums themselves became objects of trade and heirlooms. More than 200 have been found, across an area from easternIndonesia to Vietnam and parts of Southern China. (Wikipedia)

My father authored the article The Sea-Locked Lands: The diverse traditions of South East Asia in Stuart Piggott’s vast coffee table book The Dawn of Civilization: The First World Survey of Human Culture in Early Times (Thames and Hudson, 1962), which contains a section: The bronze drums of Dong-son.

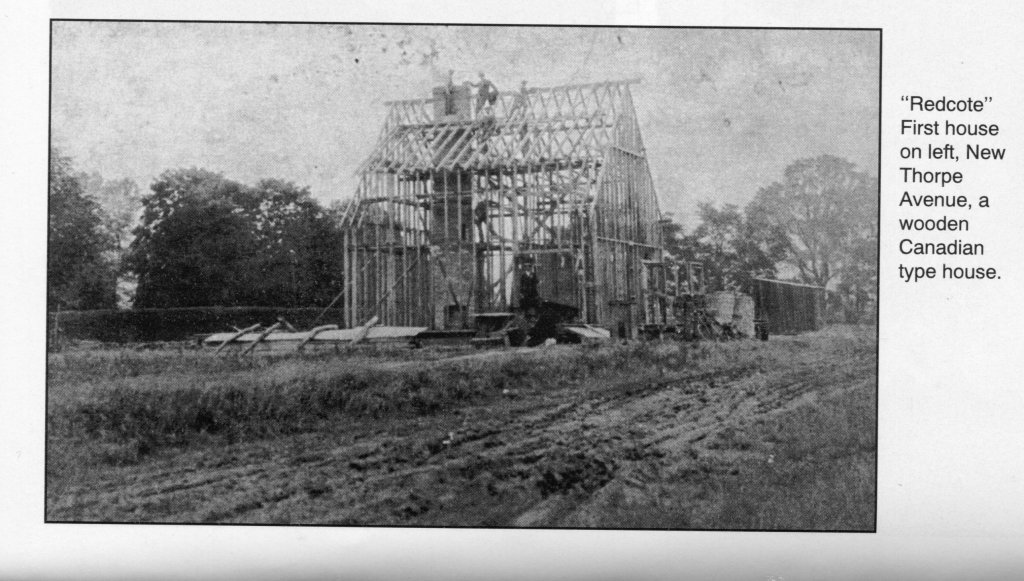

But back to rural North East Essex. We lived in a fairly large Canadian, cedar wood house, situated in the middle of a very large garden.

There are now six houses standing on the land that used to be occupied by our house and garden. How a Canadian, cedar wood house, and it was the real thing, imported from Canada in the 19th century, came to be built in a rural village in Essex is a story for itself.

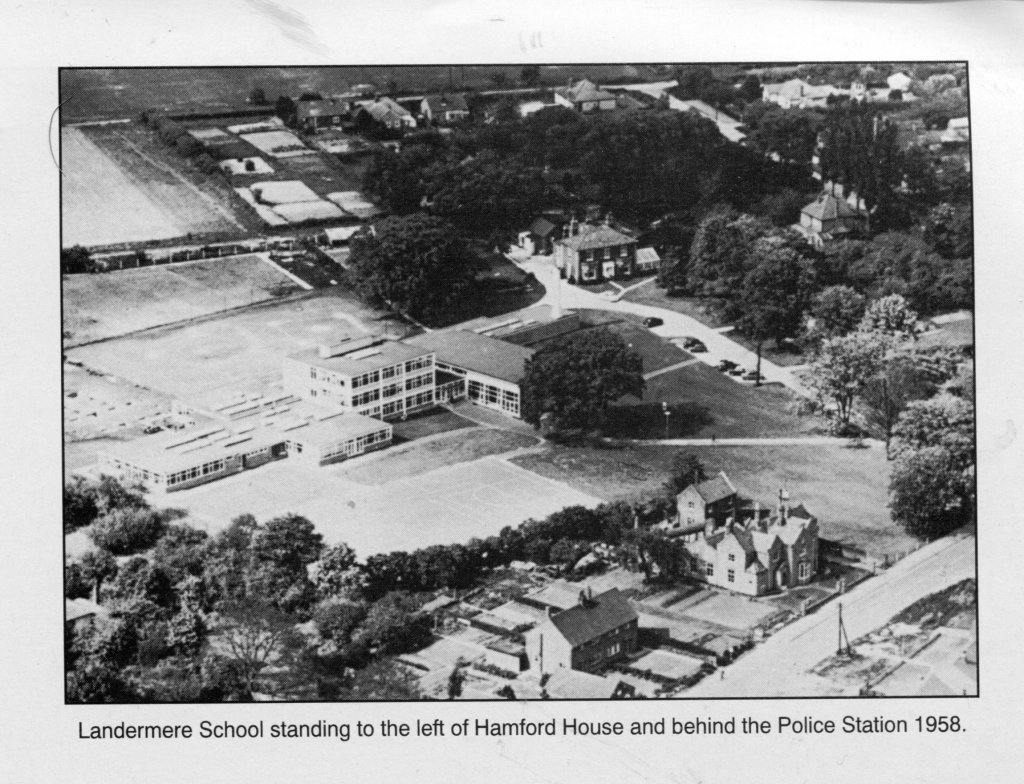

On one side our garden was bordered by a country lane and on the other side by a large country house situated in a vast park, which itself was bordered by the rather splendid Victorian police station, where my childhood best friend, the son of the police sergeant, lived.

In the 1950s the house next door and its park were compulsory purchased by the local authority to build a secondary modern school. The owners, an elderly, ex-colonial couple, retired to Dovercourt, a seaside town next to the port of Harwich. When they moved they gave my father two artefacts. The first was a very beautiful Burmese sword with a story in pictures inlaid in the blade in silver. The second was a Đông Sơn drum that they had bought on a street market in Burma!

It’s a story you couldn’t make up, an expert for the Vietnamese Đông Sơn culture gets given the Đông Sơn cultural artefact, a drum, by his next door neighbour in a North East Essex rural village! I should hasten to point out that this is not a bronze age drum, but the drums continued to be made down the centuries and this one is, I think, 18th century, but it is still a wonderful object.

When my father died I didn’t immediately inherit the drum, but it was earmarked for me in the future, staying with my stepmother in the meantime. In the last couple of years my stepmother, who is getting old but who is very efficient, has been sorting out her life and household for her eventual departure from this life. She asked me if I still wanted to have the drum and of course I said, yes please. However, when we looked into the problems of transporting it to Germany it turned out to be a very expensive project, due to its size, weight, and value for the insurance. So, we decided to shelve it for the meantime, and I said I would take it back to Germany with me when I travelled over for my stepmother’s funeral.

Recently I have been giving the topic some more thought and have reached a new conclusion. I am seventy-two years old and do not enjoy the best of health if I make it to eighty, I shall be very surprised. My stepmother, however, seems indestructible, so I looks like I shall be going to significant trouble of somehow transporting the drum to Germany for, probably, just a few years. Then whoever gets lumbered with sorting out my affairs has the problem of what to do with the drum. After discussing the problem with my stepmother, I have, with a heavy heart, decided the drum should instead be sent to auction and the proceeds donated to a charity of my stepmother’s choice.

I can, however, still claim that I almost owned a Đông Sơn drum.