As I explained in episode XII of this series where I introduced the work of the ancient Greek engineers and their machines, the discipline mechanics derives its name from the study of machines.

Greek μηχανική mēkhanikḗ, lit. “of machines” and in antiquity it is literally the discipline of the so-called simple machines: lever, wheel and axel, pulley, balance, inclined plane, wedge, and screw.

Just as some scholars during the ‘Abbāsid Caliphate studies, absorbed, criticised, and developed the works of Aristotle and John Philoponus on motion, and those of Aristotle and Ptolemaeus on astronomy, so there were others who took up the translated works of the Greek engineers such as Hero of Alexandria and Philo of Byzantium, extending and improving their work on machines. The Islamic texts on machines have an emphasis on timekeeping and hydrostatics.

For the earliest Islamic book on machines, we turn once again to the translation power house, the Persian Banū Mūsā brothers Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873); Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century) and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century), the sons of the astronomer and astrologer on the court of the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Maʾmūn, Mūsā ibn Shākir. Amongst their approximately twenty books, of which only three survived, the most famous is Kitab al-Hiyal al Naficah (Book of Ingenious Devices), which draw on knowledge of the works of Hero and Philo but also on Persian, Chinese, and Indian sources but which goes well beyond anything achieved by their Greek predecessors.

It contains designs for almost a hundred trick vessels and automata the effects of which, “were produces by a sophisticated, if empirical, use of the principles of hydrostatics, aerostatics, and mechanics. The components used included tanks, pipes, floats siphons, lever arms balanced on axles, taps with multiple borings, cone-valves , rack-and-pinion gears, and screw-and-pinion gears.”[1]

In the ninth century the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Mustaʿīn (c. 836 – 17 October 866) commissioned the philosopher, physician, mathematician, and astronomer Qusta ibn Luqa al-Ba’albakki (820–912) to translate Hero’s Mechanica, a text in which Hero explored the parallelograms of velocities, determined certain simple centres of gravity, analysed the intricate mechanical powers by which small forces are used to move large weights, discussed the problems of the two mean proportions, and estimated the forces of motion on an inclined plane, which has only survived in the Arabic translation.

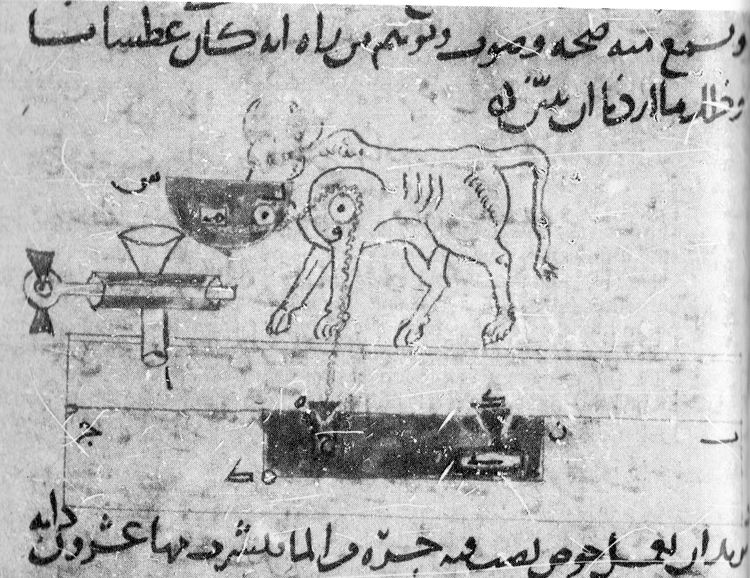

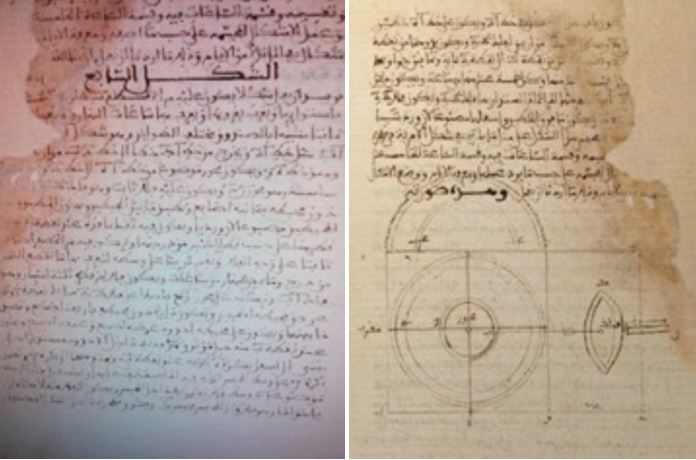

In al-Andalus in the eleventh century, the engineer Ibn Khalaf al-Murādī about whom we know almost nothing authored Kitāb al-asrār fī natā’ij al-afkār (The Book of Secrets in the Results of Ideas), which describes 31 models consisting of 15 clocks, 5 large mechanical toys (automata), 4 war machines, 2 machines for raising water from wells and one portable universal sundial.

When I looked at the science of engineering and saw that it had disappeared after its ancient heritage, that its masters have perished, and that their memories are now forgotten, I worked my wits and thoughts in secrecy about philosophical shapes and figures, which could move the mind, with effort, from nothingness to being and from idleness to motion. And I arranged these shapes one by one in drawings and explained them.

Al-Muradi, The Book of Secrets in the Results of Ideas

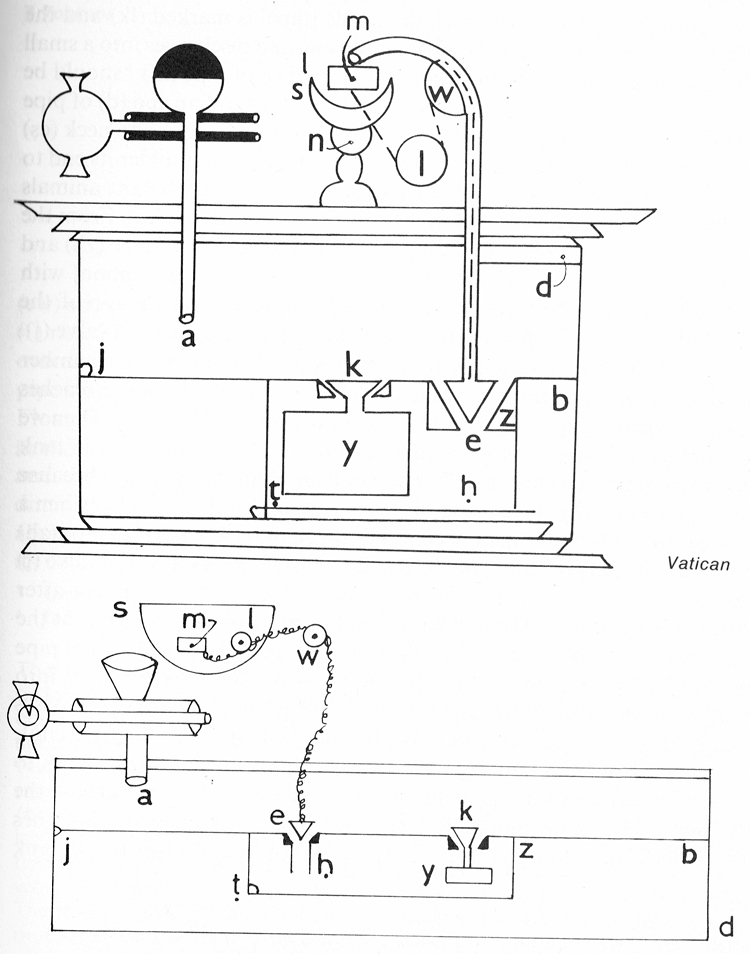

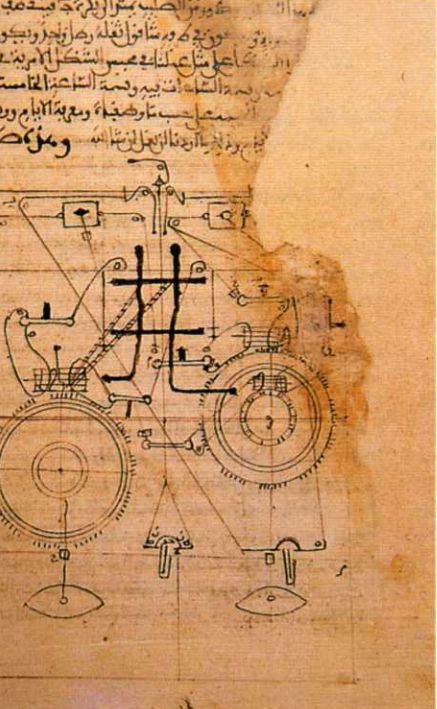

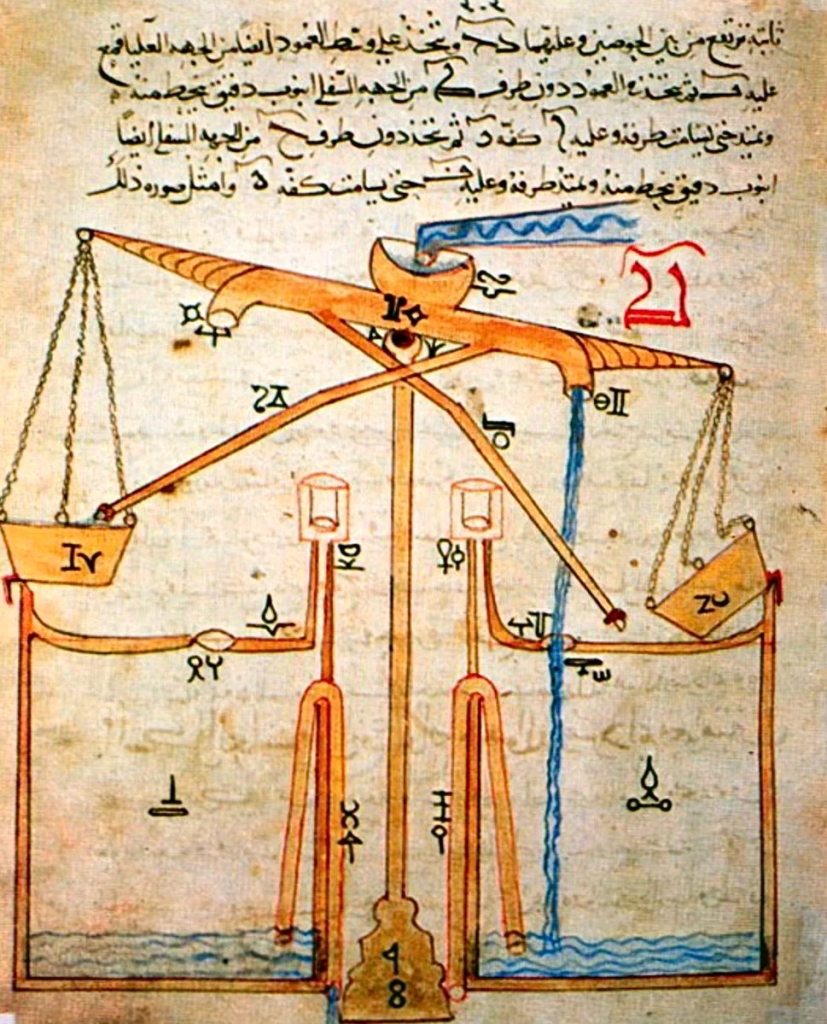

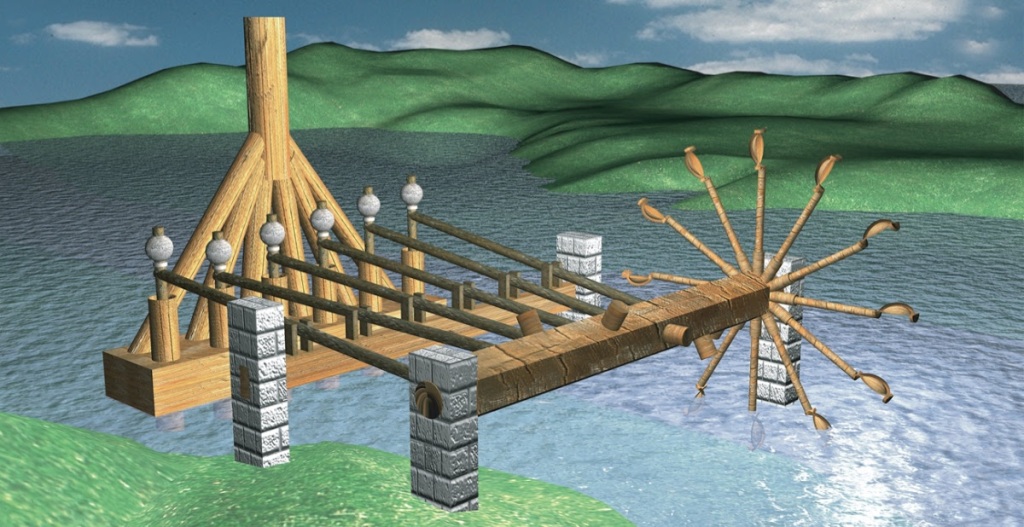

The most spectacular of all the Islamicate text on machines and mechanics is the Kitab fi ma’rifat al-hiyal al-handasiya, (The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices) commissioned in Amid (modern day Diyarbakir in Turkey) in 1206 by the Artuqid ruler Nāṣir al-Dīn Maḥmūd (ruled 1201–1222) and created by the artisan, engineer artist and mathematician Badīʿ az-Zaman Abu l-ʿIzz ibn Ismāʿīl ibn ar-Razāz al-Jazarī (1136–after 1206).

All that we know about al-Jazarī comes from his book. He was born in 1136 in Upper Mesopotamia the son of the chief engineer at the Artuklu Palace, the residence of the Mardin branch of the Artuqids the vassal rulers of Upper Mesopotamia, a position he inherited from his father. Al-Jazarī was an artisan rather than a scholar, an engineer rather than an inventor.

The book, which al-Jazarī wrote at the command of Nāsir al-Dīn, is divided into fifty chapters, grouped into six categories; I, water clocks and candle clocks (ten chapters); II, vessels and figures suitable for drinking sessions (ten chapters); III, pitchers and basins for phlebotomy and ritual washing (ten chapters); IV, fountains that change their shape and machines for the perpetual flute (ten chapters); V, machines for raising water (five chapters); and VI, miscellaneous (five chapters): a large ornamental door cast in brass and copper, a protractor, combination locks, a lock with bolts, and a small water clock. Donald R. Hill, DSB

His work was clearly derivative and he cites the Banū Mūsā, the mathematician, astronomer, and astrolabe maker Abū Ḥāmid Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al‐Ṣāghānī al‐Asṭurlābī (died, 990), Hibatullah ibn al-Husayn (d. 1139), and a Pseudo-Archimedes as sources. Many of his devices are improved models of ones described by Hero of Alexandria and Philo of Byzantium. He probably also drew on Indian and Chinese sources.

The book is clearly written in straightforward Arabic; and the text is accompanied by 173 drawings, ranging from rudimentary sketches to full page paintings. On these drawings the individual parts are in many cases marked with the letters of the Arabic alphabet, to which al-Jazarī refers in his descriptions. The drawings are usually in partial perspective; but despite considerable artistic merit, they seem rather crude to modern eyes. They are, however, effective aids to understanding the text. Donald R. Hill, DSB

The book was obviously fairly widespread in Islamicate culture judging by the number of surviving manuscripts but unlike the work of the Banū Mūsā it was first translated from the Arabic into a European language in modern times.

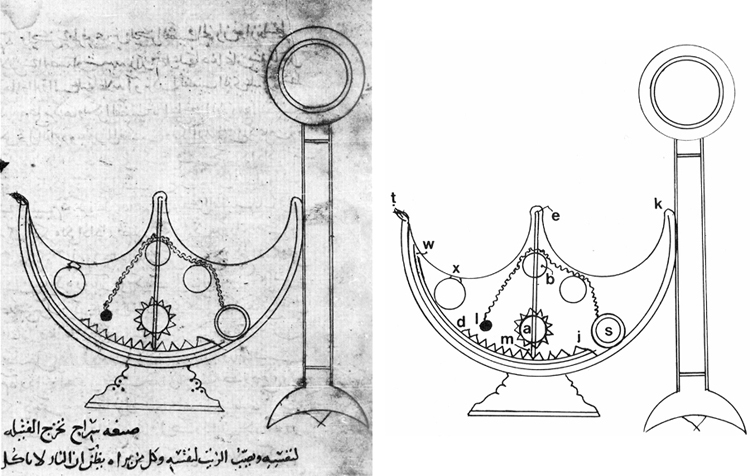

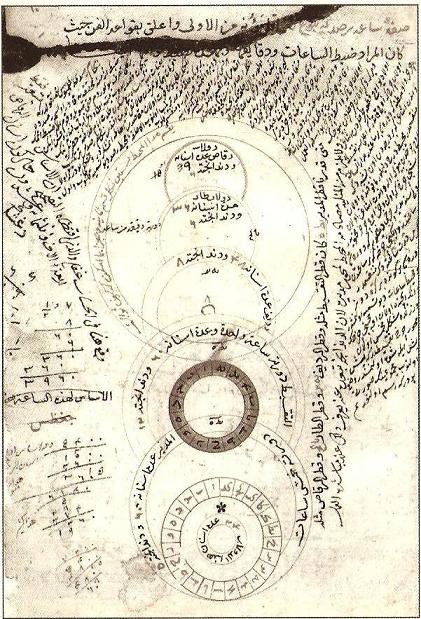

Our last Islamic engineer is the Ottoman Turk polymath Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma’ruf ash-Shami al-Asadi (1526–1585), who as we saw in the last episode designed, built, and managed the observatory in Istanbul for Sultan Murad III (1546–1595). Taqī al-Dīn is famous for his mechanical clocks about which he wrote two books.

- The Brightest Stars for the Construction of Mechanical Clocks (al–Kawākib al–durriyya fī waḍ ҁ al–bankāmāt al–dawriyya) was written by Taqī al-Dīn in 1559 and addressed mechanical-automatic clocks. This work is considered the first written work on mechanical-automatic clocks in the Islamic and Ottoman world. Taqī al-Dīn mentions that he benefited from using Samiz ‘Alī Pasha’s private library and his collection of European mechanical clocks.

- al–Ṭuruq al–saniyya fī al–ālāt al–rūḥāniyya is a second book on mechanics by Taqī al-Dīn that emphasizes the geometrical-mechanical structure of clocks, which was a topic previously observed and studied by the Banū Mūsā and al-Jazarī.

He also wrote The Sublime Methods in Spiritual Devices (al-Turuq al-saniyya fi’1-alat al-ruhaniyya) a treatise in six chapters 1) clepsydras, 2) devices for lifting weights, 3) devices for raising water, 4) fountains and continually playing flutes and kettle-drums, 5) irrigation devices, 6) self-moving spit.

The pistons of the pump were similar to drop hammers, and they could have been used to either create wood pulp for paper or to beat long strips of metal in a single pass.

The self-moving spit in part six uses an early steam turbine as motive power:

“Part Six: Making a spit which carries meat over fire so that it will rotate by itself without the power of an animal. This was made by people in several ways, and one of these is to have at the end of the spit a wheel with vanes, and opposite the wheel place a hollow pitcher made of copper with a closed head and full of water. Let the nozzle of the pitcher be opposite the vanes of the wheel. Kindle fire under the pitcher and steam will issue from its nozzle in a restricted form and it will turn the vane wheel. When the pitcher becomes empty of water bring close to it cold water in a basin and let the nozzle of the pitcher dip into the cold water. The heat will cause all the water in the basin to be attracted into the pitcher and the [the steam] will start rotating the vane wheel again.”

Naturally by Taqī al-Dīn’s time the Renaissance was in full swing in Europe and European artist-engineers were already writing their own books on machines and mechanics.

As can be seen Islamic engineers knew of and built on the work of their Greek predecessors and the work of the Banū Mūsā and Ibn Khalaf al-Murādī became known in Europe exercising an influence on the European developments in machines and mechanics. There was also an information flow in the 16th century between the observatory in Istanbul and Europe.

[1] E. R. Truitt, Medieval Robots: Mechanisms, Magic, Nature, and Art, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015 p. 20 quoting Donald Hill, “Medieval Arabic Mechanical Technology,” in Proceedings of the First International Symposium for the History of Arabic Science, Aleppo, April 5–12 1976, Aleppo: Institute forb the History of Arabic Science, 1979.