How Expanding Our Social Circles Might Be Dividing Us

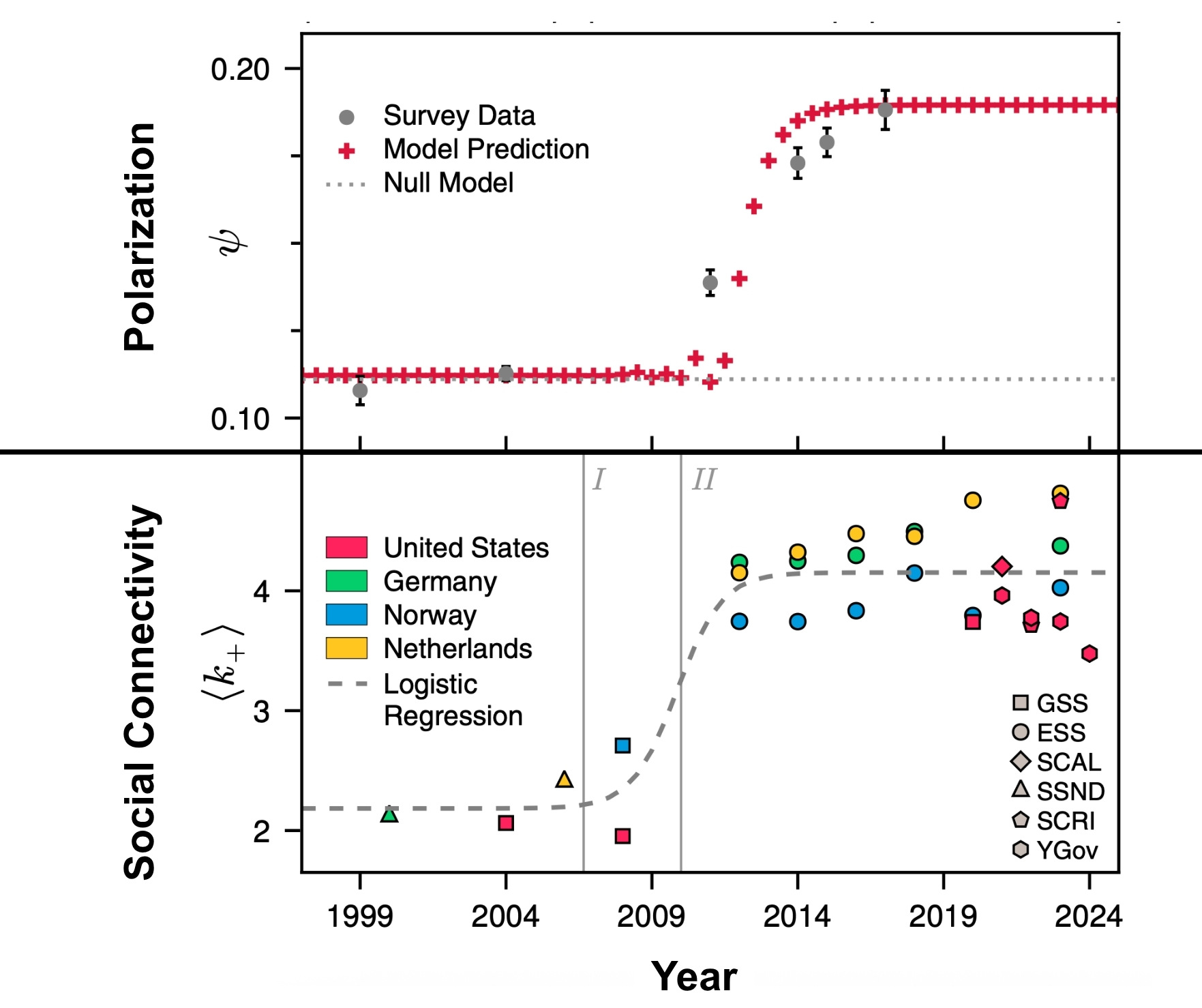

An unusual development occurred between 2008 and 2010. Americans unexpectedly reported having more close friends than ever, increasing their inner circles from an average of two to four or five. Concurrently, political division surged, a trend that researchers were able to document through extensive surveys. Now, scientists believe they understand the link between these two trends, and their findings challenge our understanding of social bonds.

Stefan Thurner and his team from the Complexity Science Hub in Vienna examined decades of survey data and uncovered a concerning contradiction: as we grow more connected, society becomes increasingly fragmented. Their mathematical model, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that this is not merely a correlation, but rather a cause-and-effect relationship stemming from the essential mathematics of network dynamics.

The Era of Just Two Friends Is Behind Us

For many decades, sociological studies depicted a stable picture of American social dynamics. Individuals typically had about two close friends, relationships capable of genuinely affecting their views on significant matters. This consistent number persisted across various studies, serving as a dependable constant amid the evolving fabric of modern existence.

Then, in 2008, things changed. The researchers tracked 30 different surveys involving over 57,000 individuals from Europe and the United States, observing a rapid increase in the number of close friendships. By 2024, the average number had risen to 4.1 close friendships. This change unfolded swiftly, concentrated in the few years when Facebook became accessible to the public and smartphones began to appear in widespread usage.

Jan Korbel, a researcher at the Complexity Science Hub, expressed surprise regarding this discovery in their published findings.

“Around 2008, we witnessed a sharp rise from an average of two close friends to four or five.”

At the same time, political views became more entrenched. The team analyzed over 27,000 surveys from the Pew Research Center, which has posed identical political questions to Americans since 1999. In that initial year, only 14 percent of participants exhibited consistently liberal perspectives. By 2017, this increased to 31 percent. Conservative viewpoints followed a similar trend, growing from 6 percent to 16 percent. The neutral ground, where individuals held a blend of liberal and conservative views, diminished.

When Connections Lead to Division

The researchers developed a mathematical model to explore the relationship between these observations. Their findings are akin to a phase transition in physics, similar to when water suddenly turns into ice. Below a certain connectivity threshold, societies remain fluid and diverse. However, crossing that critical point, somewhere between three and four close connections, leads to a reconfiguration: fewer groups that are more tightly knit, with either hostile or nonexistent links among them.

Markus Hofer from the Complexity Science Hub elucidates the mechanism within the research.

“As network density increases with additional connections, polarization among the collective inevitably escalates.”

The reasoning may be counterintuitive but is compelling. With more close friends, you are exposed to differing viewpoints more frequently. This might seem it would foster tolerance and greater flexibility in thought. Instead, it leads to increased friction. Every disagreement becomes a reason to retreat into groups where opinions align. Additionally, having more friendships means there is less need to invest effort in maintaining relationships that are challenging.

Thurner provides a frank thought experiment. If you have just two friends, you are likely to endure almost anything to keep them. However, with five friends, if one becomes difficult, you can simply let that relationship decline. You have alternatives. The motivation to bridge differences diminishes, replaced by the convenience of curating a network that supports existing beliefs.

The outcome is not merely polarization but fragmentation, a term the researchers use with caution. Individuals no longer just disagree. They categorize themselves into factions that barely interact, linked only by tenuous threads of animosity. Democracy, reliant on active participation from all societal segments in collective decision-making, starts to falter when groups can no longer communicate.

The timeline suggests social media and smartphones act as amplifiers of this trend; however, the researchers refrain from asserting direct causation. Although these technologies did not generate the mathematical principles driving fragmentation, they could have propelled societies past the crucial threshold where these dynamics dominate. The phase transition was always feasible; the digital era merely rendered it unavoidable.

What remains uncertain is whether this trend can be reversed or if societies that have crossed this divide will continue down this path.