Thirty kilograms of deadwood and grass. Temperatures surpassing 500 degrees Celsius. Hours of collective effort to keep the flames alive. Almost 10,000 years ago, a small band of hunter-gatherers in northern Malawi conducted what researchers now identify as Africa’s oldest documented cremation, converting the death of a single woman into a memorable social act.

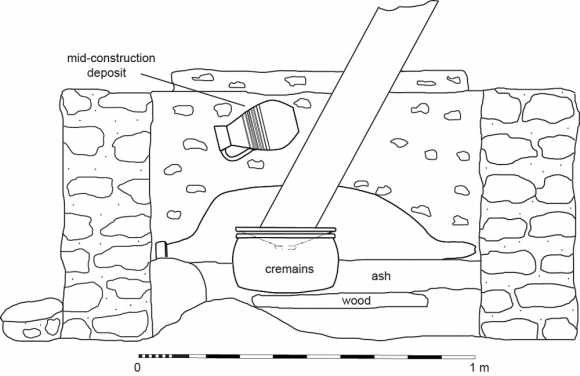

The finding, outlined in a recent study published in Science Advances, resulted from excavations at Hora 1, a rock shelter nestled under the granite outcrop of Mount Hora. There, archaeologists discovered a substantial ash deposit approximately the size of a queen-sized bed, containing 170 bone fragments from one individual: an adult woman who stood nearly five feet tall and passed away between ages 18 and 60.

This was more than mere body disposal. Cremation necessitates careful planning, ongoing supervision, and considerable fuel resources. Open-air pyres need to achieve and sustain high temperatures through repeated fuel additions. This endeavor challenges the notion of social complexity within early African foraging societies, which have often been viewed as possessing limited ritualistic practices.

What the Bones Disclose

The remains of the woman narrate a specific tale. Signs of cracking and changes in coloration suggest she was cremated while still having flesh, likely within days following her death. Several limb bones exhibit cut marks, implying portions of her body were defleshed or disarticulated during the ceremony. Notably, fragments of the skull and teeth are missing from the pyre, though these typically endure the high temperatures of cremation.

Microscopic examination of the sediments indicates that the fire was carefully controlled. The community regularly added fuel to uphold the heat needed for complete combustion. Stone tools discovered within the ash core may have been intentionally placed there, possibly as funerary offerings or integrated into the body during the ritual.

“High-resolution, multiproxy reconstruction of the ritual connected to cremation and its later deposition reveals intricate mortuary practices among ancient African foraging groups, demonstrating considerable social investment and interaction with natural landscape features,” explains Jessica I. Cerezo-Roman, lead author and associate professor of anthropology.

This discovery shifts back the timeline for this unique mortuary custom on the continent. While there are older examples of burned human remains found globally, Hora 1 houses the world’s oldest recognized in situ adult pyre, indicating that the fire was constructed, and the body was cremated at the exact location where it was uncovered.

A Site Remembered for Generations

Archaeological findings reveal that Hora 1 served as a burial site for thousands of years, with most individuals buried intact. This woman remains the only recognized cremation from this location. However, large fires continued to be lit at the same site for about 500 years following her death, with no further cremations taking place.

This pattern suggests that the location of the pyre held significance long after the event had occurred. The site seems to have operated as a lasting landmark, a place revisited and retained in the living community’s memory. The researchers contend that the granite outcrop acted as a natural monument, solidifying social identity and collective history.

In everyday language, this indicates far more than logistical arrangements for funerals. The organization, perseverance, and communal attention required highlight the occurrence of a public ceremony, not a solitary act. The repeated visits to the site across centuries imply that the woman’s death transformed her community’s relationship with fire, space, and ancestral connections.

The reason this particular individual received such distinct treatment compared to others interred at Hora 1 remains unknown. Nevertheless, the care, effort, and enduring memory suggest her death held meaning that extended far beyond her existence. In the ash beneath Mount Hora, archaeologists identify signs of a society capable of turning mortality into lasting social significance.

Science Advances: 10.1126/sciadv.adz9554

There’s no paywall here

If our reporting has enlightened or inspired you, kindly consider making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of size, empowers us to continue providing accurate, engaging, and reliable science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support helps us keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!