The coastlines of our planet are partially influenced by two glaciers that remain largely unknown to the general public. Thwaites and Pine Island are located in West Antarctica and together they function as plugs preventing ice from flowing into the ocean, potentially causing sea levels to rise by multiple meters. Researchers have monitored these glaciers for many years, but the looming question that keeps many awake is whether current events signify the beginning of a far more concerning situation.

A research group spearheaded by Keiji Horikawa from the University of Toyama sought answers from the distant past. By examining sediment cores extracted from the floor of the Amundsen Sea, the scientists discovered that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreated significantly inland at least five times throughout the Pliocene Epoch, a warm interval spanning from 5.3 to 2.58 million years ago when global temperatures were approximately 3 to 4 degrees Celsius higher than those of today. During that period, sea levels were over 15 meters higher than they currently are.

The results, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that the ice sheet isn’t necessarily a stable, unchanging landmark. Under certain conditions, it can remain stable for extended times, only to rapidly retreat.

Two Shades of Sediment Convey the Narrative

The proof arises from sediments gathered during the International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 379 at a location on the Amundsen Sea continental rise. Within the cores, dense gray clays signify cold glacial intervals when ice enveloped the continental shelf. These layers exhibit a smooth, finely layered texture. In contrast, thinner greenish sections reveal a different scenario. They are rich in microscopic algae that only flourish in open, ice-free waters.

These warmer sediment layers also possess debris transported by icebergs: small rock fragments that have become embedded in glaciers on land, carried to the ocean via calving icebergs, and subsequently deposited on the seabed as the ice melted. The team identified 14 notable melt-event periods occurring between 4.65 and 3.33 million years ago.

To determine the origin of the rocks, the researchers analyzed the isotope ratios of strontium, neodymium, and lead found in the fine sediment. These ratios serve as chemical identifiers tracing back to the source rocks. At specific intervals, notably around 3.88, 3.6, and 3.33 million years ago, a unique signature emerged that could solely originate from the Ellsworth-Whitmore Mountains situated deep in the Antarctic interior.

This represents the crucial discovery. Those mountains are located far from the current position of the ice margin. For the debris to reach the ocean, the ice must have significantly retreated towards the continent’s core.

The Memories of Ice

The sediment record illustrates a recurring cycle. During colder periods, ice covered the continental shelf and remained stable. As temperatures increased, the base of the ice began to thaw, leading to a retreat of the ice margin. During peak warmth, huge icebergs would calve off and release their rocky load into the ocean. When cooler conditions resumed, the ice sheet would regrow.

This cycle repeated itself numerous times. The researchers merged geochemical data with simulations of ice-sheet behavior to correlate retreat episodes with sediment movement patterns. In the modeled context, retreating ice generates large icebergs that transport sediment across the shelf. When colder conditions return, the regenerating ice pushes previously laid-down sediments towards the shelf’s edge, where ocean currents carry finer materials to the drilling site.

“We aimed to explore whether the WAIS completely dissolved during the Pliocene, how frequently these events took place, and what caused them,” explains Horikawa.

The ice did not disappear forever. The isotopic indicators from the interior do not show up in every warm phase, implying that the ice sheet occasionally endured even during periods of Pliocene warmth. Yet, the pattern is sufficiently evident: given enough warming, the system reaches a tipping point and retreats swiftly.

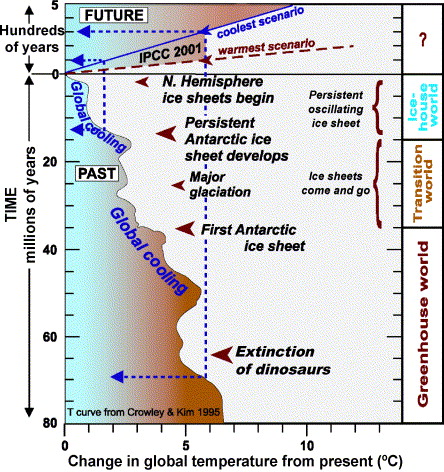

The unsettling aspect lies in the temperature context. The Pliocene epoch was not significantly warmer than forecasts for the upcoming century. If the ice sheet demonstrated such sensitivity millions of years back, the current trends offer little reassurance. The ancient sediments serve not only as a record but as a caution regarding the consequences of the ice relinquishing its hold.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: 10.1073/pnas.2508341122

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us