If the future leans towards electricity, then there’s a pressing requirement for significantly more batteries. To achieve a threefold increase in renewable energy, as committed by 133 nations at COP28, battery storage capabilities must rise by six times by 2030, while the need for electric vehicle batteries is expected to expand seven times, based on data from the International Energy Agency. The limitations imposed by varying application demands and raw material availability, in conjunction with worries about the security and safety of supply chains, are motivating the industry to innovate new battery technologies.

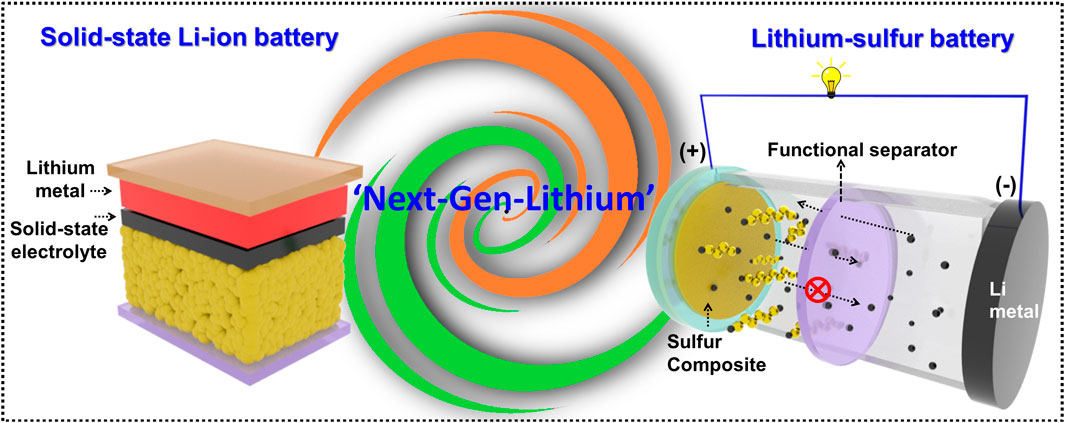

Solid-state and sodium-ion batteries are progressing rapidly, but lithium–sulfur, lithium–air, potassium-ion, and aluminum-ion batteries are also contenders. However, experts caution that the speed of these advancements is outpacing researchers’ capacities to comprehend and assess their safety implications. Determining what is more or less safe is a complex issue, as it involves numerous factors.

Different chemistries come with their unique advantages and disadvantages regarding lifespan and energy density, but ‘the key factor is that we comprehend what they entail, and that those who may be exposed also recognize what they are,’ states Donal Finegan, a scientist at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in the US. For instance, first responders should be aware of the gases emitted during a vehicle battery blaze.

‘When conducting evaluations at the materials level, one gains insights into their behavior, but at the pack level, it becomes a challenging question because behavior varies with scale,’ Finegan adds. The manner in which a battery has been utilized, along with its age, significantly impacts its resilience to thermal or mechanical stress.

Even seemingly minor alterations, such as reducing cobalt levels in the cathode of lithium nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries, can negatively affect reaction kinetics, potentially making a cell more dangerous, Finegan explains.

### Thermal runaway and fire hazards in emerging batteries

In events of fire, batteries based on sulfur will generate toxic hydrogen sulfide, while certain sodium-ion and potassium-ion chemistries may emit hydrogen cyanide or hydrogen fluoride during thermal runaway. Another often-neglected research domain, according to Finegan, concerns particulate emissions during battery fires. ‘Although manufacturers may grasp the nature of the particulate, the community lacks this understanding, which poses a significant challenge. We need to conduct more experiments and characterizations to educate first responders and provide regulatory authorities with the data necessary to make well-informed decisions regarding PPE for first responders,’ for instance.

While lithium-ion technology continues to advance in efforts to enhance battery longevity and capability, even the current chemistry remains not entirely comprehended.

In early November, Stellantis issued a recall for some plug-in hybrid Jeeps and SUVs following reports of multiple fires. The batteries produced by Samsung SDI indicated that ‘the most probable cause is damage to the separator combined with other intricate interactions within the battery cells.’

‘I test batteries of various sizes, up to complete packs … and with each instance, we learn something new – and so do the battery manufacturers,’ notes Paul Christensen, a lithium-ion battery safety expert at Newcastle University. ‘The difficulty lies in the fact that extrapolation cannot be made from cell level to module level, from module level to pack level, or from pack level to electric vehicle.’ He emphasizes the necessity for new advanced facilities capable of testing not only lithium-ion batteries but also the upcoming generation of batteries.

Phoebe O’Hara, who heads clean power initiatives at the Energy Transitions Commission, a coalition of stakeholders in the energy sector, asserts that ‘lithium has undergone two decades of innovation and development along with numerous accidents and incidents to learn from. Sodium and solid-state technology are merely at the initial stages of this journey, and they will have to traverse through a similar cycle.’

The innovative solid-state technology presents higher energy density and faster charging capabilities. It’s named such due to its elimination of flammable liquid electrolytes that dominate today’s batteries – offering a reduced risk of thermal runaway.

What replaces them are polymers like polyethylene oxide, along with inorganic solids such as sulfides and oxides. However, additional modifications also occur: the presence of a solid electrolyte eliminates the requirement for a separate insulating barrier between the cathode and anode, and the anode consists of lithium metal instead of carbon or graphite.

‘The shift towards solid-state batteries primarily stems from their ability to mitigate many safety concerns linked with liquid electrolytes, including thermal runaway,’ comments Sylwia Waluś, a battery technology specialist at the UK’s Faraday Institution. ‘However, “safer” does not equate to “risk-free.” These systems still contain substantial energy in a confined space, necessitating careful handling.’

Recent findings in France regarding solid-state cells not yet available commercially revealed that under high temperature and pressure circumstances, thermal runaway did occur due to significantly greater heat flow compared to liquid electrolyte cells. Nonetheless, only half as much gas was emitted compared to liquid.