In the normal blog post rotation, a book review should be due today. However, instead today’s post is a literature review, listing and describing books on the histories of the theories of vision, spectacles, and telescopes, with the latter coming first as they are the actual main theme of the review. I announced my intention to do this is response to a regular readers request, so long ago I’ve forgotten when, and I was recently reminded of that announcement when someone on Twitter asked me if one of the history of the telescope books, which I own is any good; it is as I will explain later.

The classical standard text on the early history of the telescope is Albert van Helden’s The Invention of the Telescope, which was first published as a paper in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society in 1977 but has long been available as a monograph, the second edition appearing in 2008 to celebrate the 400thanniversary of the invention of the telescope.

Van Helden presents and analyses all of the early literature related to the emergence of the telescope in the first decade of the seventeenth century, as well as earlier descriptions of instruments similar to the telescope that proceeded it His text contains full quotes from the original literature in their source languages followed by English translations. It is justifiably called a classic and is a must read for anybody seriously studying the history of the telescope.

Van Helden’s text includes the historical references to Zacharias Janssen (1585–before 1632), as one of the candidates for the invention of the telescope. In 2008, there was a big conference in Middelburg, in the Netherlands, where the telescope first emerged, to celebrate that 400th anniversary; I was there! In the conference proceedings, The origins of the telescope (edited by Albert van Helden, Sven Dupré, Rob van Gent, Huib Zuidervaart, and published by KNAW Press, Amsterdam, 2010) there is a paper by Huib J. Zuidervaart, The ‘true inventor’ of the telescope. A survey of 400 years of debate, which clearly shows that Zacharias Janssen was not an inventor of the telescope.

The entire proceedings contain an amazing collection of papers on all possible aspects of the history of the telescope by an all star cast of the world’s best historians of optics. It is available as a printed book but is also available as an open access e-book online.

The two books I’ve described so far only really deal with the origins of the telescope; we now turn our attention to books that delve further into the history of the telescope. A classic that is substantially older than van Helden’s The Invention of the Telescope is Henry King’s The History of the Telescope, which was originally published by Charles Griffin & Co. Ltd. In 1955 and then republished by Dover in 1979.

It opens with a short chapter on the beginning of astronomical observation that is followed by an even shorter chapter on the history of lenses and optics that ends with Lipperhey and his invention of the refracting telescope, with the rival claims of Metius and Jansen. There follows chapter for chapter a chronological history of telescopes and their user and uses beginning with Galileo and ending around 1950 with the construction of the Jodrell Bank radio telescope. Despite the fact that it is dated, it is well researched and well written and can still be read with profit.

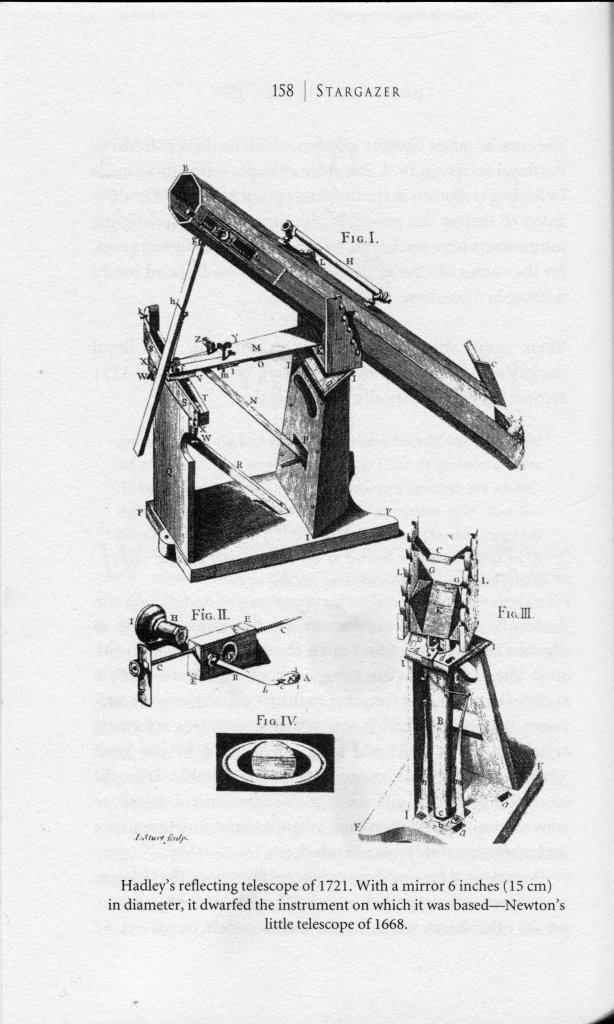

More up to date is Fred Watson’s Stargazer the life and times of the Telescope (Da Capo Press, 2005).

As with King, Watson opens with the pre-telescopic era and the various reports of things that might have been telescope but probably weren’t prior to 1608 and Lipperhey.

He then takes his reader on an episodic journey through the history of the telescope down to the present day, ending with plans and discussion of a new generation of super telescopes. A well-researched and well written book, which I found a pleasure to read and highly informative.

I managed an absolute classic in Middelburg in 2008. I got into a conversation with another participant at the conference and during the exchange started to talk about something from Watson’s book blithely unaware that my conversation partner was the man himself! Mildly embarrassing but also somewhat amusing.

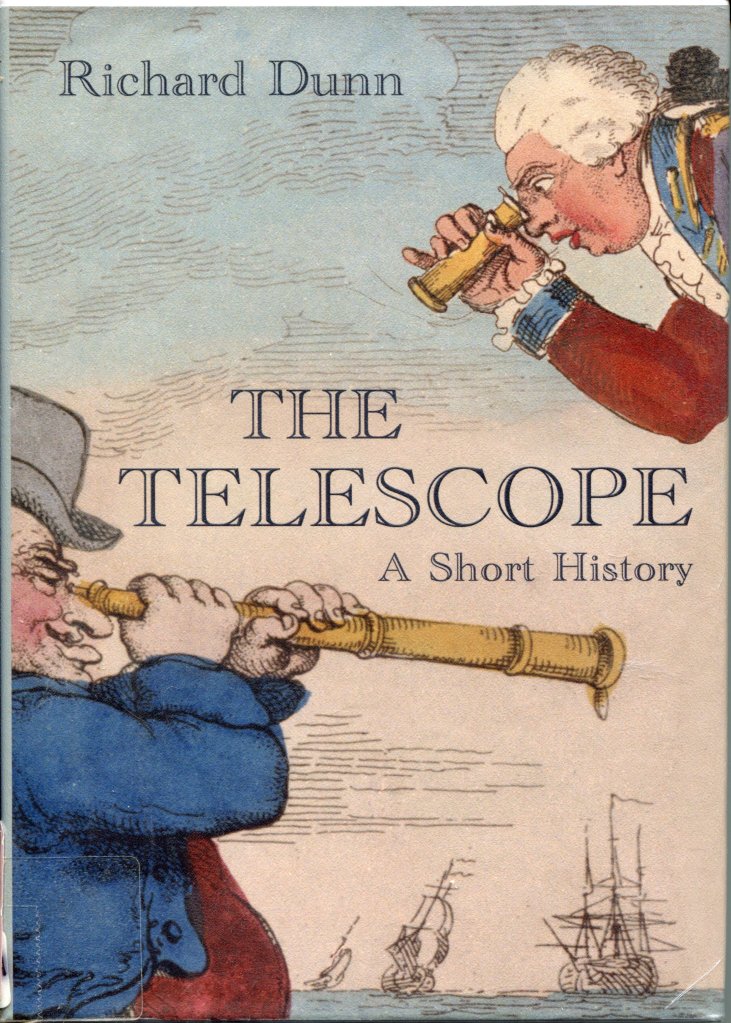

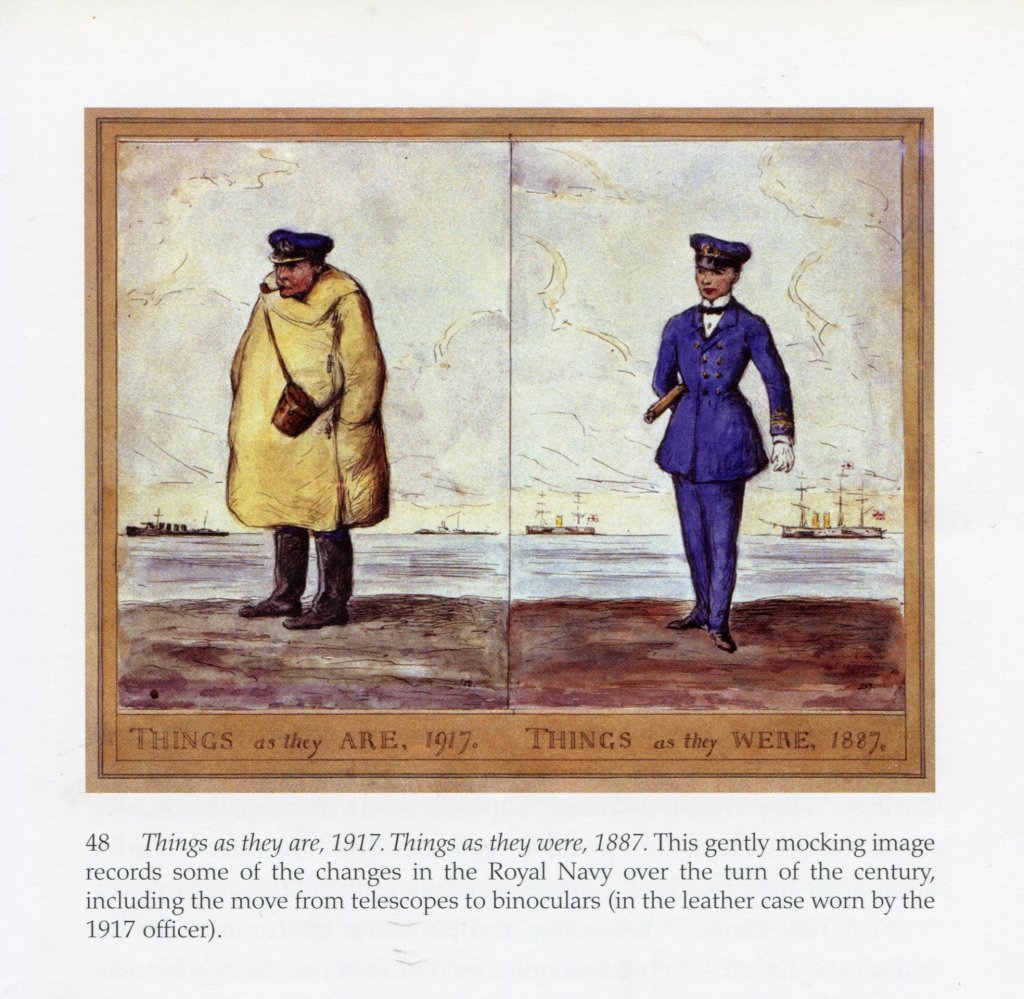

For those readers, who are interested but don’t want to plough their way through a dense academic tome on the history of the telescope but would prefer something more digestible, I heartily recommend Richard Dunn’s The Telescope: A Short History (National Maritime Museum, 2009, Conway, 2011).

Dunn was then curator at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, which has its own excellent collection of telescopes, and is now Keeper of Technologies and Engineering at the Science Museum. The chapters of his book are more topic orientated rather than purely chronological. Beautifully illustrated, it is a comparatively light introduction to the history of the telescope, as I said ideal for those interested but not necessarily prepared to take a deep dive into the subject. This was the book I got asked about recently on Twitter.

Of a somewhat different nature is Marvin Bolt’s Telescopes Though the Looking Glass (Adler Planetarium, 2009).

This is actually a catalogue of an exhibition that Bolt curated at the Adler upon his return from the 2008 conference in Middelburg. I will quote Bolt’s brief description of the exhibition in full because it captures the general concept of all of the history of the telescope texts:

The exhibition and catalogue address four themed zones. The first, the pretelescope zone, addresses ways in which people have looked at the sky and tried to make sense of it, using their surrounding landscapes or relatively simple tools to develop an understanding or model of the Universe. Zone two presents the invention of the telescope, the challenges it brought to the Earth-centered Universe, and the beautiful craftsmanship and ornamentation of some of the earliest surviving examples in the world. In zone three, the technical challenges of improving telescopes led to variations in design and materials; the telescopes also became popular devices with brand-name recognition. Zone four displays the culmination of the refracting telescope and the emergence of spectroscopy, leading to the marvels of modern telescopes: some see wavelengths beyond the optical realm, others detect invisible particles, a few compensate for atmospheric turbulence, while still others travel beyond the Earth’s atmosphere into space.

Each exhibit is illustrated with a description on the facing page. If you can find a copy, it’s a great introduction to the history of the telescope.

The ‘if you can find a copy’, illustrates a major problem with this bibliography. Because they only have a limited appeal and target readership, many of the books I am describing are out of print and you have to hunt around to find second-hand copies. Several of mine were bought second-hand.

Galileo, of course, gets a whole telescope bibliography to himself. I’ll start with Eileen Reeves’ excellent Galileo’s Glassworks (Harvard University Press, 2008).

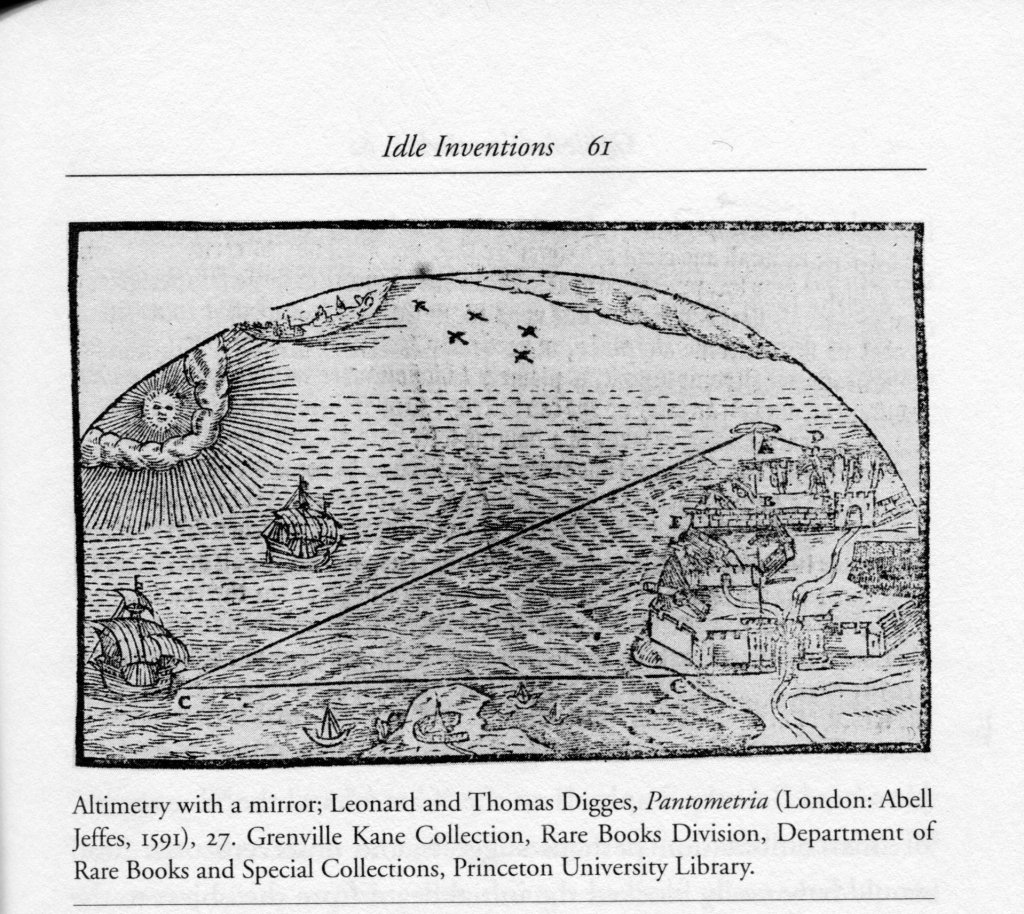

There was a significant gap between Galileo first hearing about the new invention from the Netherlands and the manufacture of his own first telescope. In her book Reeves argues convincingly that Galileo at first thought that the new instrument was somehow based on mirrors and spent substantial time and effort trying to work out how. Reeves backs this up with a detailed account of the history of (magical) mirrors that allowed their owners to see great distances.

The book also contains much information on the critical period before and during the early period of telescope manufacture. A fascinating, thoroughly researched, and beautifully book.

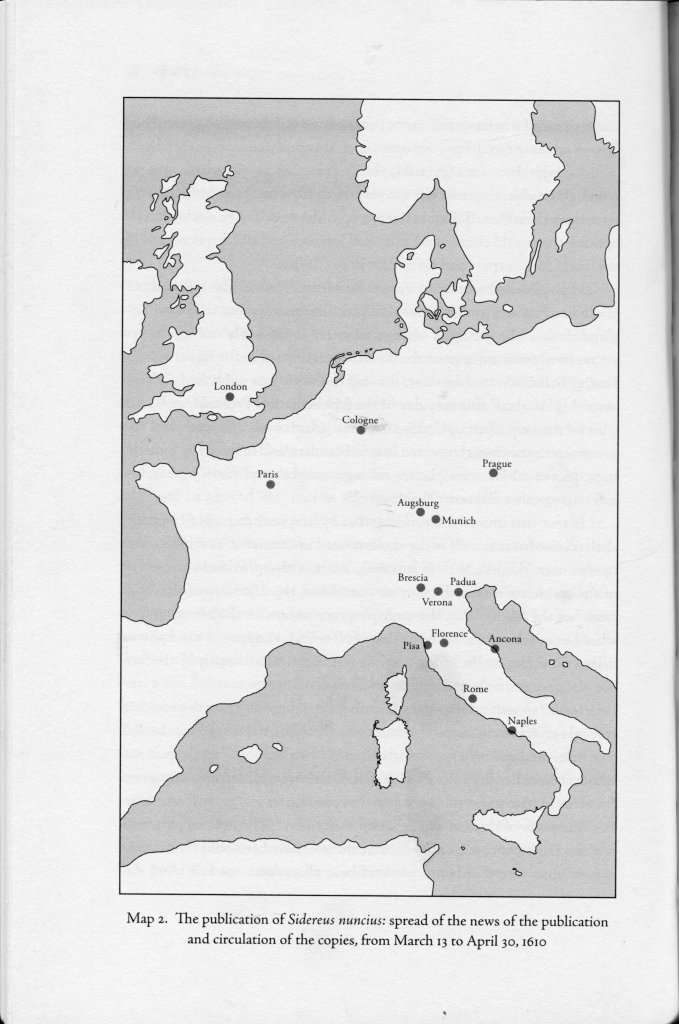

Galileo’s Telescopes: A European Story (Harvard University Press, 2015) by Massimo Bucciantini, Michele Camerota, and Franco Giudice and translated by Catherine Bolton describes in great detail the spread of the influence of Galileo’s publications on his telescopic discoveries and the distribution of the instruments that he manufactured throughout Europe and the influence that he exercised thereby.

An important contribution to the literature on the early telescope and its influence, well researched and excellently presented.

The same phenomenon, Galileo’s telescopes and their influence, is treated from a different angle by Mario Biagioli in his Galileo’s Instruments of Credit: Telescopes, Images, Secrecy (University of Chicago Press, 2007).

This can be read alone but is much better read as a sequel, which it was, to Biagioli’s Galileo Courtier: The Practice of Science in The Culture of Absolutism (University of Chicago Press, 1993).

In the earlier book Biagioli basically presents Galileo as a social climber, who uses his scientific career to win status within the political climate of Northern and Middle Italy at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Hustling for status and favour, Biagioli argues, I think correctly, that Galileo’s downfall was largely a product of the mechanisms of absolutist politics. Having raised Galileo up as a favourite at his papal court, Maffeo Barberini, Pope Urban VIII, then cast him down as a demonstration of his absolute power during a period of political crisis. This treatment of court favourites was quite common in absolutist regimes throughout Europe.

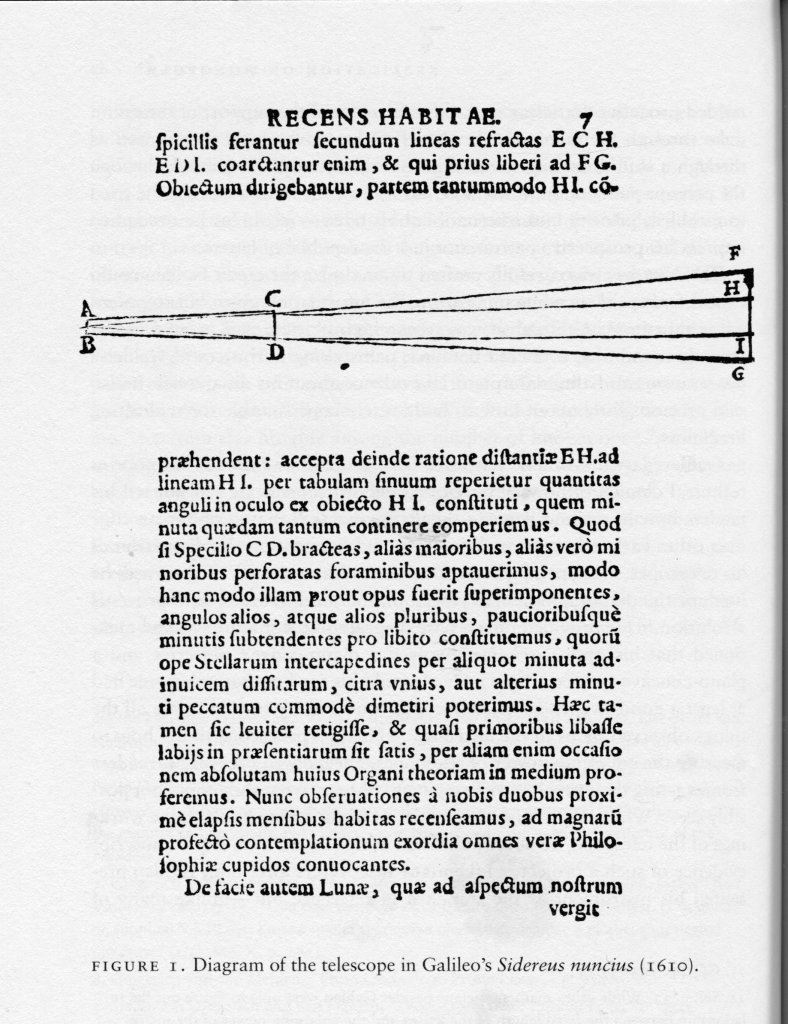

In his second volume, Biagioli shows how Galileo, having become the telescope man throughout Europe, through the publication of his Sidereus Nuncius in 1610, manufactured telescopes together with his instrument maker, who usually gets left out of the story, and distributed them as favours throughout Europe.

However, he did not give them to other mathematicians and astronomers, who could have used them to confirm Galileo’s discoveries or made new ones of their own, but to powerful figures within the Catholic Church and political potentates, in order to raise his own social status. In his defence it should be pointed out Galileo was not alone in doing this. It was common practice for Renaissance mathematici to design and manufacture high class scientific instruments as gifts for potential aristocratic patrons.

Both of Biagioli’s books are excellent and highly recommended for anybody interested in Galileo, his telescopes, his telescopic discoveries, and his use of them within a socio-politic context rather than a scientific one.

Having looked briefly at the social, political, and cultural contexts of the telescope and Galileo’s use of the instrument and his discoveries, it should be obvious that the advent of the telescope and its impact was not just scientific. Two further books by Eileen Reeves investigate the impact of the new culture of visual awareness in two non-scientific areas.

Her Painting the Heavens: Art and Science in the Age of Galileo (Princeton University Press, 1997) explores the impact that the new telescopic astronomical discoveries had on the work of a group of leading contemporary artists.

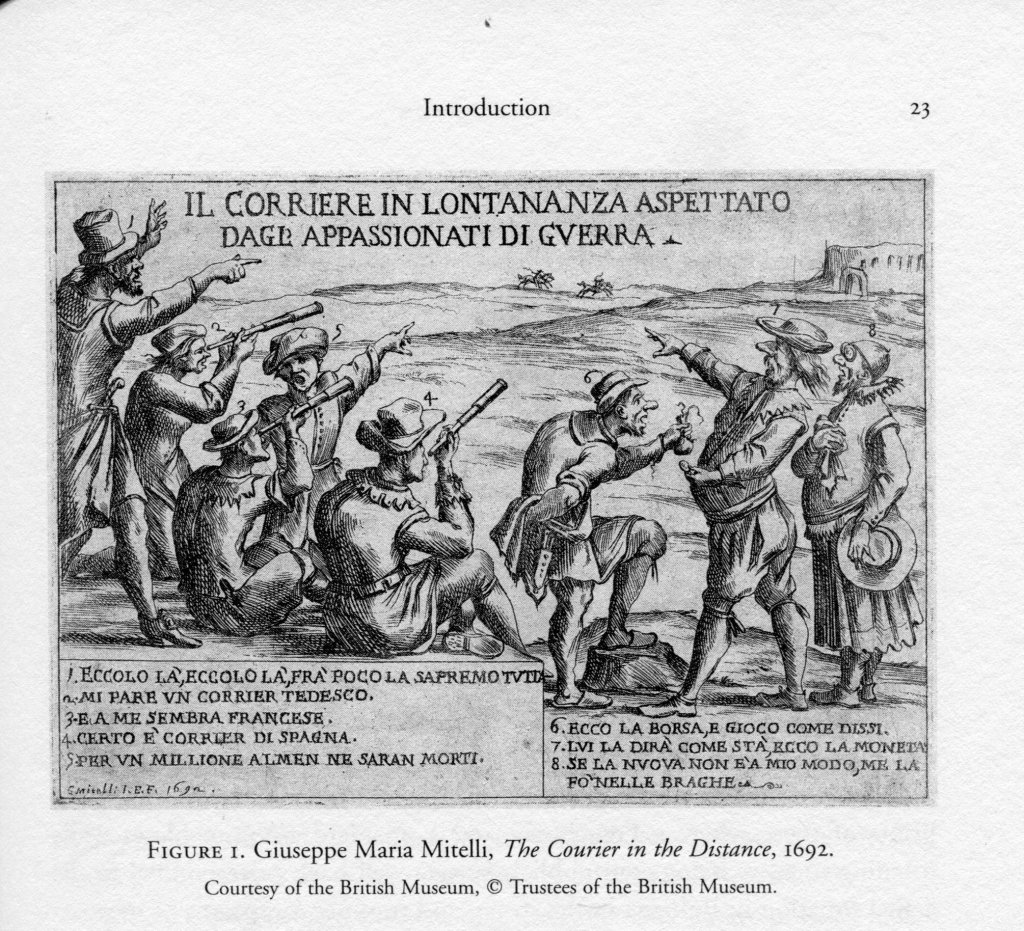

Her Evening News: Optics, Astronomy, and Journalism in Early Modern Europe(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).

The weekly newssheets began to emerge in Early Modern Europe almost simultaneously with the invention of the telescope and the publication of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius. To quote the publishers blurb:

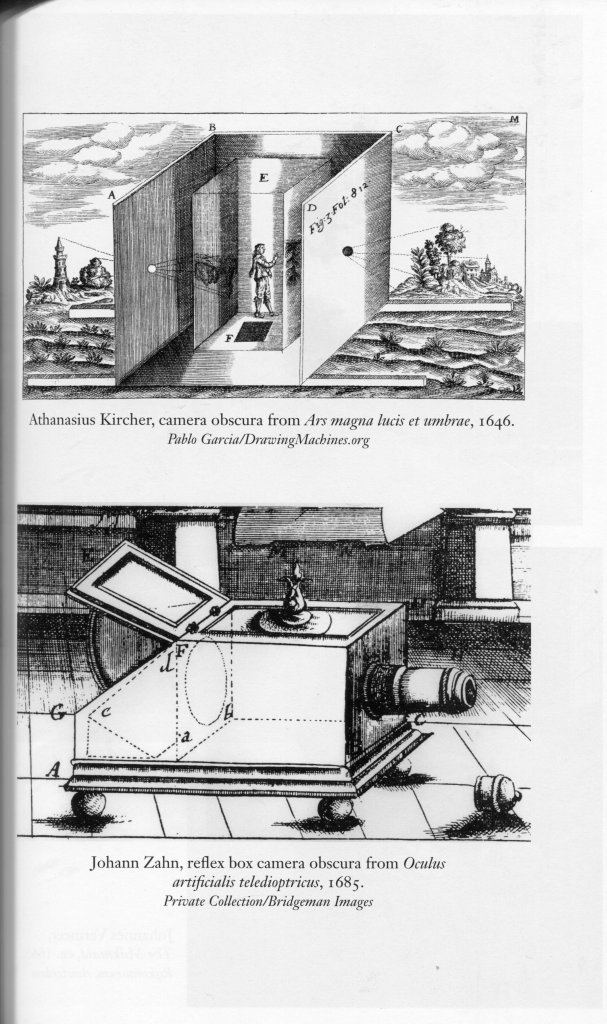

Early modern news writers and consumers often understood journalistic texts in terms of recent developments in optics and astronomy, Reeves demonstrates, even as many of the first discussions of telescopic phenomena such as planetary satellites, lunar craters, sunspots, and comets were conditioned by accounts of current events. She charts how the deployment of particular technologies of vision—the telescope and the camera obscura—were adapted to comply with evolving notions of objectivity, censorship, and civic awareness. Detailing the differences between various types of printed and manuscript news and the importance of regional, national, and religious distinctions, Evening News emphasizes the ways in which information moved between high and low genres and across geographical and confessional boundaries in the first decades of the seventeenth century.

Changing direction, the man who is credited with being the first to publicly present a working telescope Hans Lipperhey (c. 1570–1619) in Middelburg in 1608, was a professional spectacle maker. This is in no way surprising as spectacle makers were the artisans, who worked with lenses. This means if one wants to understand the invention of the telescope, one must also take a look at the history of spectacles. Above all one needs to answer the questions, how did spectacle come to be invented and given that spectacles first emerged in the late thirteenth century, why did it take more than two hundred years before somebody invented the telescope?

There are two books that answer these questions in great detail of which the first is Rolf Willach’s magisterial Long Route to the Invention of the Telescope: A Life of Influence and Exile (American Philosophical Society, 2008), like van Helden’s The Invention of the Telescope, published in English both as a journal article in the society’s transactions and as a separate monograph.

It also appears in English in the volume The origins of the telescope described above. His essay was originally published in German in Der Meister und die Fernrohre: Das Wechselspiel zwischen Astronomie und Optik in der Geschichte: Festschrift zum 85. Geburtstag von Rolf Riekher[1] herausgeben von Jürgen Hamel und Inge Keil, Acta Historica Astronomia Vol. 33, Verlag Harri Deutsch, 2007.

For those of my readers who can read German this volume contains a large collection of excellent papers on the history of the telescope. A couple of them are even in English.

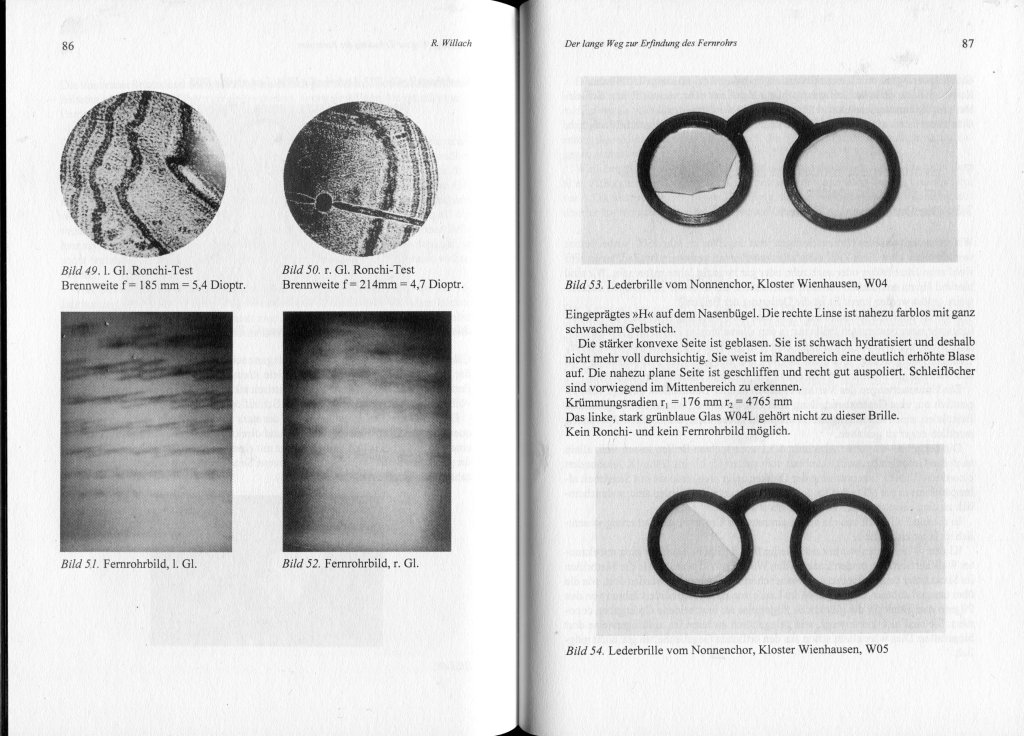

The number of different publications of Willach’s essay signify its ground-breaking status in the histories of spectacles and telescopes. Based on his very extensive empirical investigations he hypothesises that the invention of spectacles was made by monks working in medieval cloisters, cutting and polishing gemstones to decorate reliquaries, the containers for holy relics. At the other end of the two hundred years, he showed that the clue to constructing a successful telescope lay in stopping down the eyepiece lens with a mask. This is because early lenses were inaccurately ground, and the outer edges of the lens distorted the image. By masking off the outer edges, the image became comparatively sharp and usable.

Equally impressive is Vincent Ilardi’s Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes (Memoires of the American Philosophical Society, Band 259, 2007).

This is the definitive account of the Early Modern history of spectacles. Ilardi was a diplomatic historian, who studied a vast convolute of trade documents and correspondence in order to reconstruct the history of spectacles in the first two centuries of their existence. I have read this book twice but do not own a copy as it is prohibitively expensive, thank God for libraries. Iladi should have held a lecture in Middelburg in September 2008 but he was already dying of prostate cancer, which deprived the world of his excellence in January 2009.

The histories of spectacles and telescopes are, of course, just integral parts of the much wider history of optics. Optics was originally the theory of vision, how do we see? How do our eyes perceive the world around us bringing information of everything within our field of vision into our brain for processing.

The absolute classic, which outlines the various theories developed from the ancient Greeks down to Johannes Kepler at the beginning of the seventeenth century and the advent of the telescope is David C. Lindberg’s Theories of Vision from Al-Kindi to Kepler (University of Chicago Press, 1976).

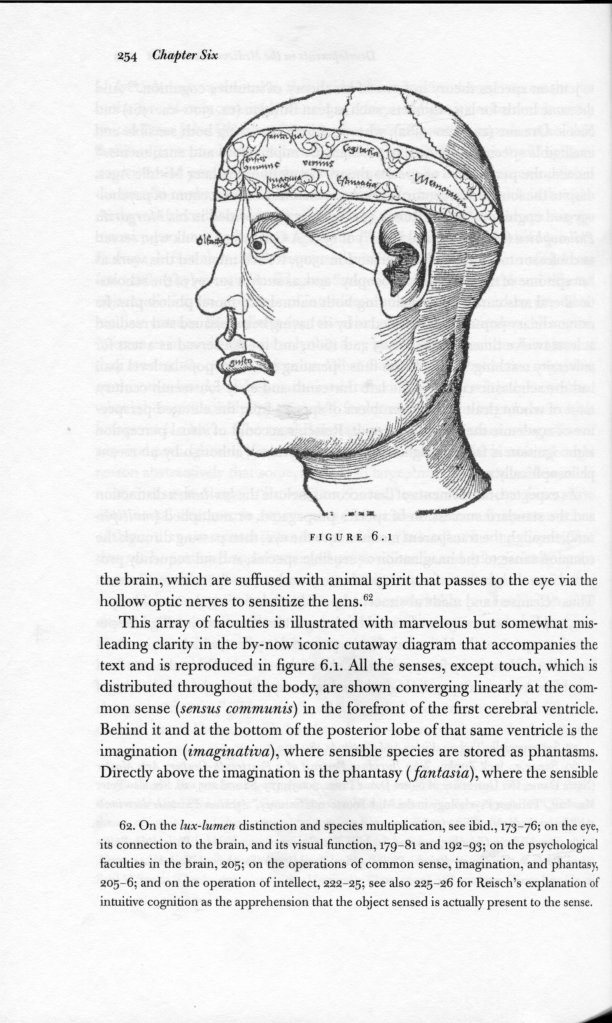

Popular wisdom claims that the ancient Greeks believed that we see with a fire that the eyes emit to touch and illuminate the objects seen. This is in simplistic form the extramission theory of vision of Plato. Lindberg explains that this was only one of several extramission and intromission (rays entering the eyes) theories of vision held by different individuals and schools of philosophy in ancient Greece. He also presents the geometric opticians–Euclid, Ptolemaeus, Heron–who propagated a mathematical extramission theory.

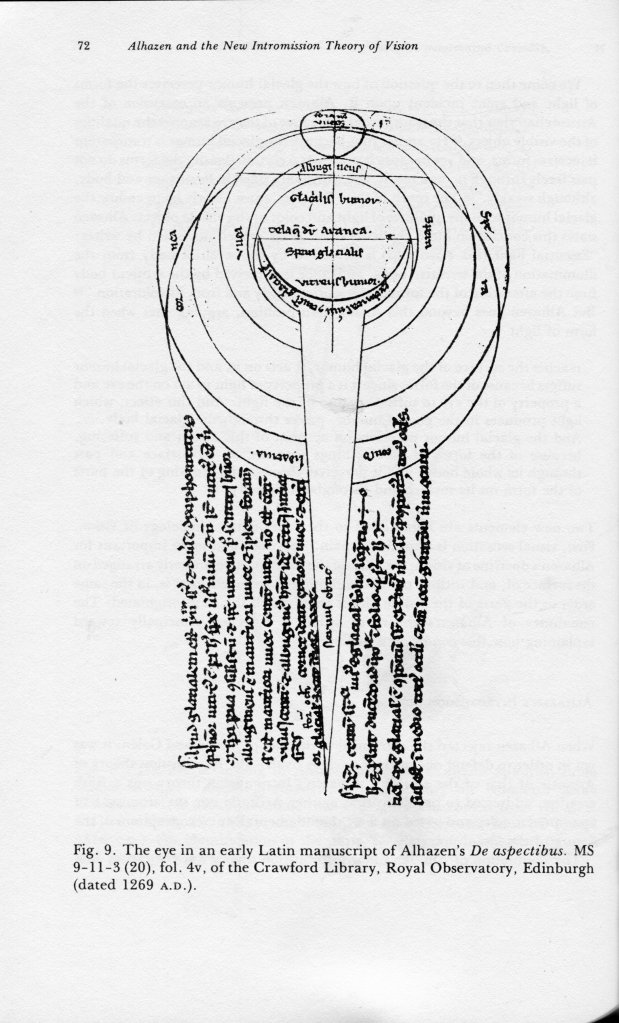

Moving on he shows how these theories were assimilated by Islamic scholars and how al-Kindi supported a Euclidian extramission theory but also developed his punctiform theory of reflection, which states that light is reflected from every point on an object in every direction. Enter al-Haytham, who produced a synthesis of an intromission theory, geometrical optics, and al-Kindi’s punctiform theory of reflection, which when translated into Latin in the thirteenth century became the so-called perspectivist theory, which led the field in Europe right down to Kepler. Lindberg sees Kepler as the last of the perspectivists. The book is a historical tour de force. If you are really interested, Lindberg has a long list of excellent academic papers investigating individual topics in medieval optics.

Even an absolute classic can be surpassed, and this has happened to Lindberg’s masterpiece. A. Mark Smith was a doctoral student of Lindberg’s and followed in his master’s footsteps becoming a brilliant historian of optics. His synthesis is From Sight to Light (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

His narrative follows that of Lindberg, but in greater detail and including many figure that Lindberg did not feature. The biggest difference come at the end, unlike Lindberg, he does not consider Kepler the last of the perspectivists but rather the first of a new direction in the optics. He argues his case very convincingly and I think he in probably correct.

If I were to recommend just one of the two, then it would have to be Smith and that despite the fact that the Lindberg was one of those turning point books in my own development. Of course, I think you should read both of them! Smith, like his mentor, has a very long list of papers and book on optics, all of which are recommended reading.

Both Lindberg and Smith stop at the beginning of the seventeenth century, although Smith has a short capital at the end sketching the further developments during the century. If you want to follow the story further then I recommend Oliver Darrigol’s A History of Optics: From Greek Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century (OUP, 2012).

Darrigol deals with the passage from the Greeks to Kepler in the first thirty-six pages of his books and devotes the rest to developing the story from there down to the end of the nineteenth century with Stoke, Poincare et al.

As I noted above when talking about Galileo and his telescopic discoveries, the new possibilities revealed by the new instruments and the new theories of optics went well beyond the boundaries of science touching on other areas such as culture, politics and society. They literally changed people’s perceptions of the world in which they lived. I will briefly mention three books which deal with this, a by no means exhaustive list.

The first one that I read was Svetlana Alpers’ The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century(University of Chicago Press, 1984).

As we have already seen with Eileen Revees’ Painting the Heavens: Art and Science in the Age ofGalileo art visually reflected the new developments in optics. To quote a review of Alpers’ book:

“The art historian after Erwin Panofsky and Ernst Gombrich is not only participating in an activity of great intellectual excitement; he is raising and exploring issues which lie very much at the centre of psychology, of the sciences and of history itself. Svetlana Alpers’s study of 17th-century Dutch painting is a splendid example of this excitement and of the centrality of art history among current disciples. Professor Alpers puts forward a vividly argued thesis. There is, she says, a truly fundamental dichotomy between the art of the Italian Renaissance and that of the Dutch masters. . . . Italian art is the primary expression of a ‘textual culture,’ this is to say of a culture which seeks emblematic, allegorical or philosophical meanings in a serious painting. Alberti, Vasari and the many other theoreticians of the Italian Renaissance teach us to ‘read’ a painting, and to read it in depth so as to elicit and construe its several levels of signification. The world of Dutch art, by the contrast, arises from and enacts a truly ‘visual culture.’ It serves and energises a system of values in which meaning is not ‘read’ but ‘seen,’ in which new knowledge is visually recorded.”—George Steiner, Sunday Times

My second book is Stuart Clark’s Vanities of the Eye: Vision in Early Modern European Culture (OUP, 2007).

Once again to quote the back cover blurb:

Vanities of the Eye investigates the cultural history of the senses in early modern Europe, a time in which the nature and reliability of human vision was the focus of much debate. In medicine, art theory, science, religion, and philosophy, sight came to be characterized as uncertain or paradoxical-mental images no longer resembled the external world. Was seeing really believing? Stuart Clark explores the controversial debates of the time-from the fantasies and hallucinations of melancholia, to the illusions of magic, art, demonic deceptions, and witchcraft. The truth and function of religious images and the authenticity of miracles and visions were also questioned with new vigor, affecting such contemporary works as Macbeth- a play deeply concerned with the dangers of visual illusion. Clark also contends that there was a close connection between these debates and the ways in which philosophers such as Descartes and Hobbes developed new theories on the relationship between the real and virtual. Original, highly accessible, and a major contribution to our understanding of European culture, Vanities of the Eye will be of great interest to a wide range of historians and anyone interested in the true nature of seeing.

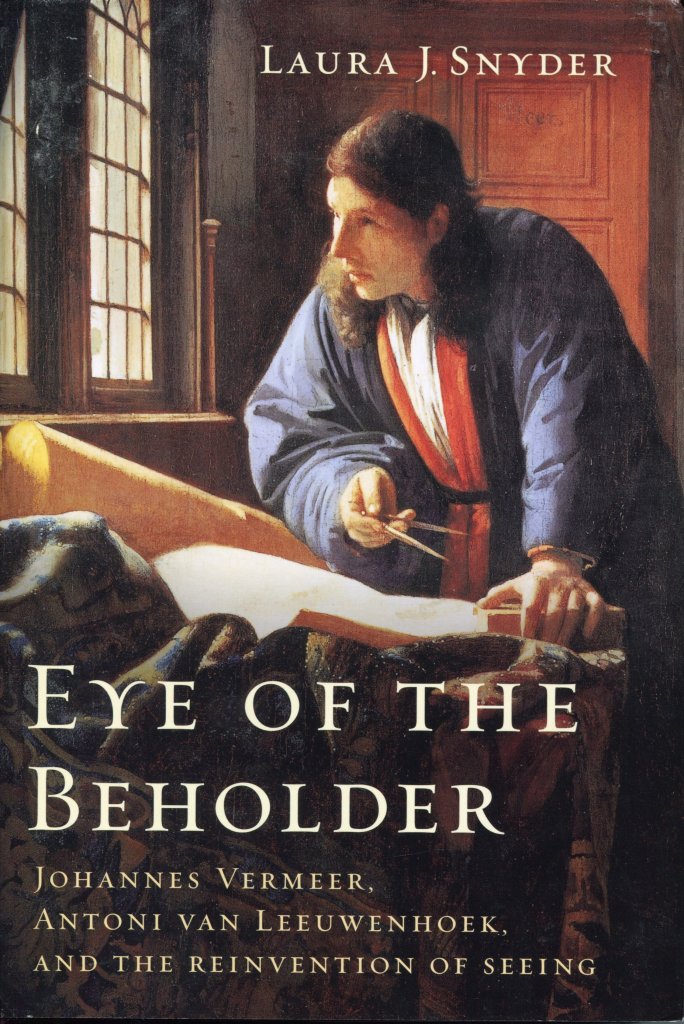

The Last of my three is Laura J Snyder’s Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing (W. W. Norton, 2015):

Once again resorting to publisher’s blurb:

By the early 17th century the Scientific Revolution was well under way. Philosophers and scientists were throwing off the yoke of ancient authority to peer at nature and the cosmos through microscopes and telescopes.

In October 1632, in the small town of Delft in the Dutch Republic, two geniuses were born who would bring about a seismic shift in the idea of what it meant to see the world. One was Johannes Vermeer, whose experiments with lenses and a camera obscura taught him how we see under different conditions of light and helped him create the most luminous works of art ever beheld. The other was Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, whose work with microscopes revealed a previously unimagined realm of minuscule creatures.

By intertwining the biographies of these two men, Laura Snyder tells the story of a historical moment in both art and science that revolutionized how we see the world today.

I’m going to close this overlong literature review with two books that I don’t think you’ll be able to get hold of, but you might get lucky. Peter Louwman is a rich Dutchman, who has a very impressive automobile museum in De Haag. The museum also houses a massive historical collection of telescopes and binoculars.

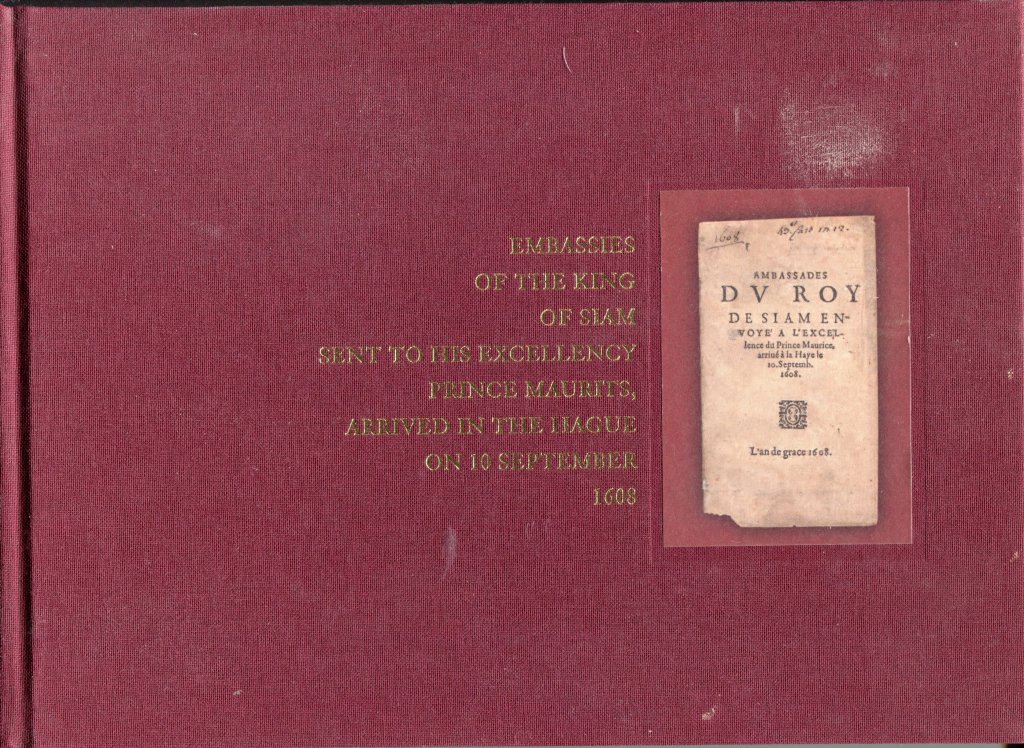

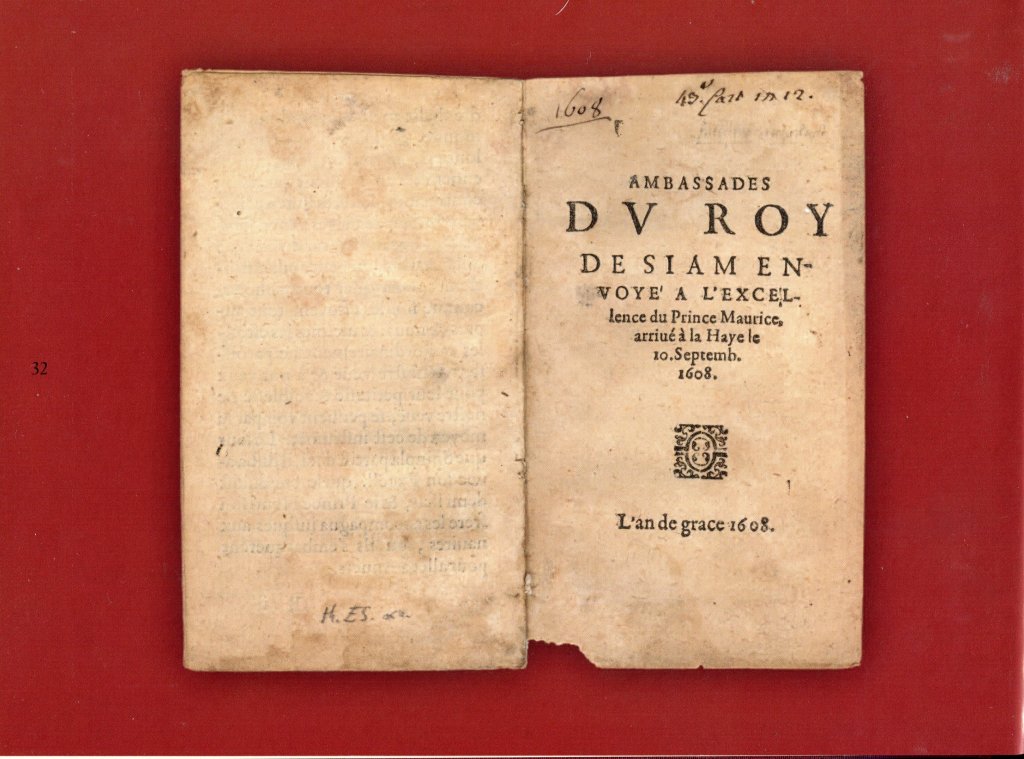

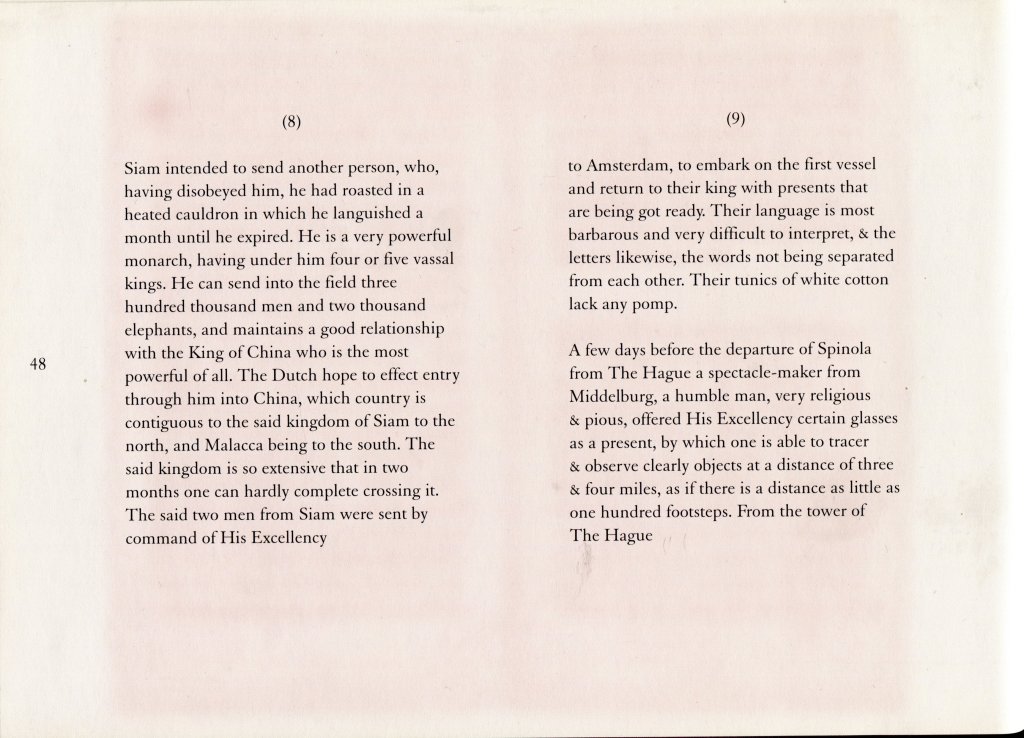

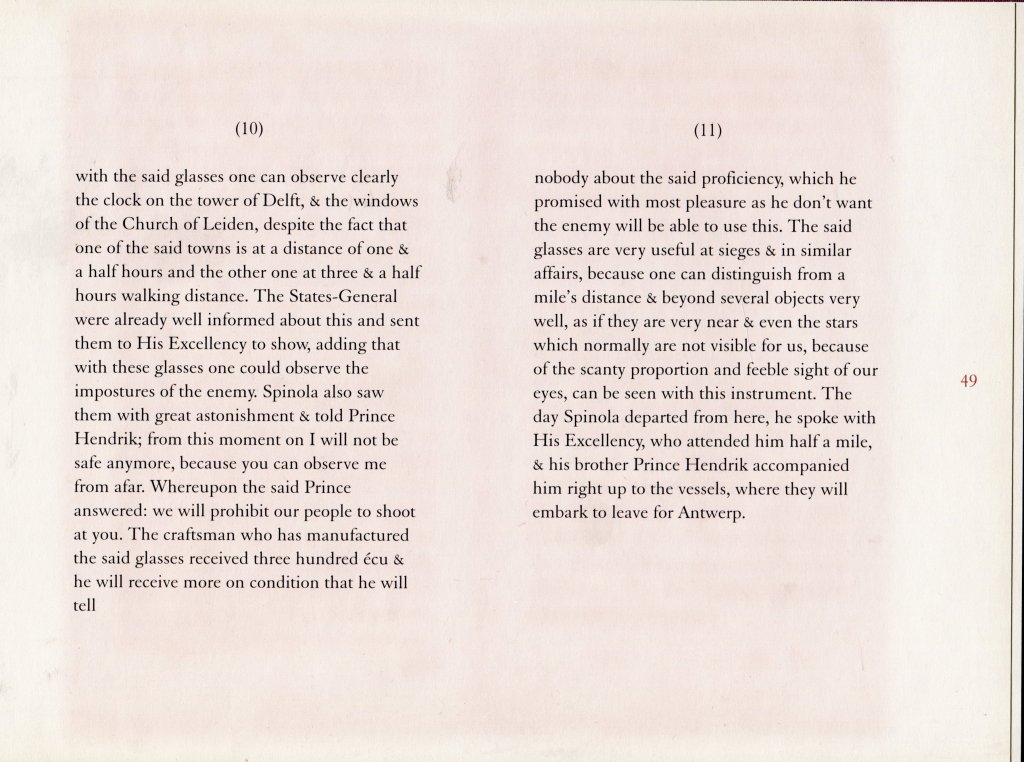

For the 400th anniversary conference in Middelburg Louwman produced a wonderful annotated edition of the French newsletter reporting on the visit of the Ambassador of Siam to Den Haag in September 1608, which contains a description of Lipperhey’s demonstration of his telescope to the assembled delegates of the peace conference taking place there.

This special edition contains an explanatory introduction, a facsimile of the newsletter,

a French transcription, and an English as well as a Dutch translation.

Every participant in the conference received a copy and I think it’s the best goody that I’ve every received at a conference. I think for a time it was on sale in the museum shop but that no longer appears to be the case.

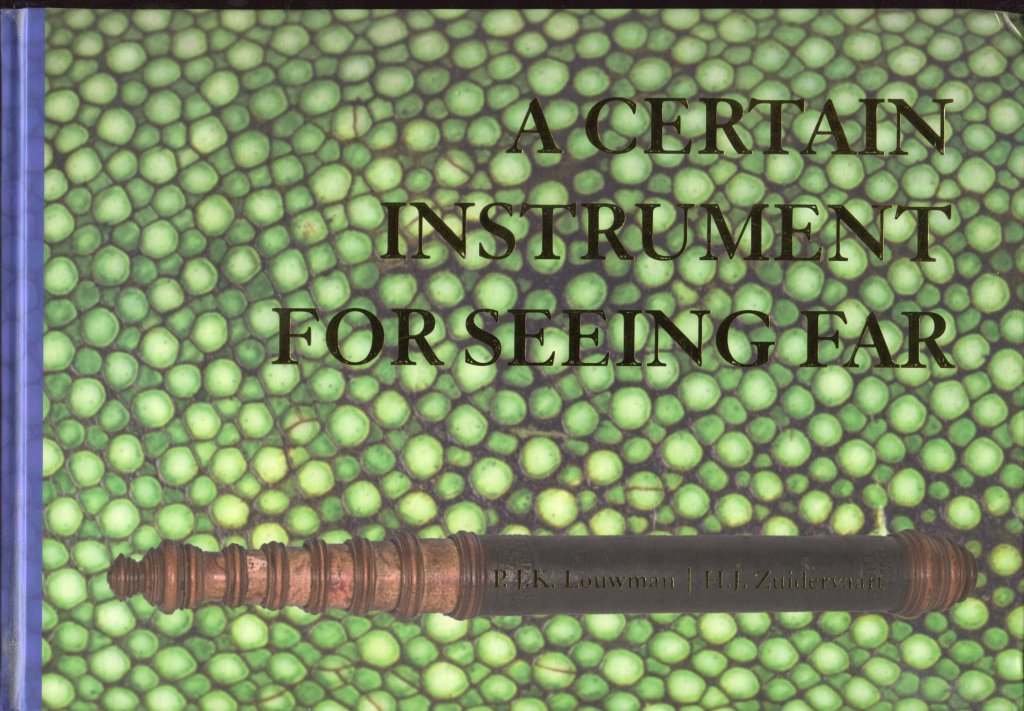

Another Louwman publication is a wonderful catalogue of the Louwman Collection of Historic Telescopes, A Certain Instrument for Seeing Far by P.J.K. Louwman and H. J. Zuidervaart (2013), which definitely used to be sold by the museum, because I bought one, but no longer seems to be available.

I’m not trying to impress my readers with all the books that I’ve read on the history of optics and the telescopic but trying to make clear that if you truly want to understand that history, the road that led up to the invention of the telescope, its impact as a scientific instrument, and its impact outside of the direct field of science then you have to extend your scope and dig deep.

[1] Rolf Riekher was a leading German optician and historian of optics, who bought me a cup of tea and a piece of cake on a sunny afternoon in Middelburg in 2008.