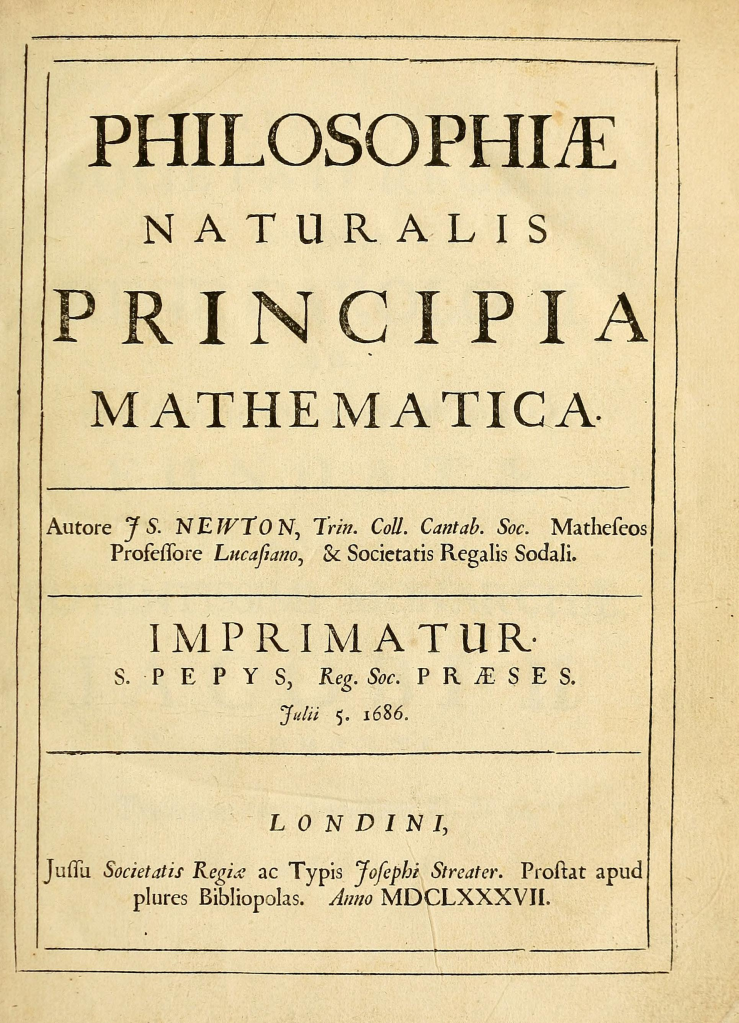

There are a series of legendary quotes that are associated with Isaac Newton and one of the most oft repeated is his, If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants. This leads people to inquire, who perchance those giants were and almost invariable with reference to his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687) they state with authority, Galileo Galilei. Apart from the fact that it simply isn’t true there is another basic problem with this attribution, Newton’s statement has absolutely nothing to do with his Principia and was in fact written eight years before the Principia was published.

When Newton published his first ever paper, A Serie’s of Quere’s Propounded by Mr. Isaac Newton, to be Determin’d by Experiments, Positively and Directly Concluding His New Theory of Light and Colours; and Here Recommended to the Industry of the Lovers of Experimental Philosophy, as they Were Generously Imparted to the Publisher in a Letter of the Said Mr. Newtons of July 8.1672 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, he got attacked on all sides most virulently by Robert Hooke (1635–1703), then England’s leading authority on all things optical. Hooke’s criticism boiled down to his claim that the paper contained very little of worth and what it did contain he had already discovered himself. He also objected very strongly, as did also Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695), that Newton had used his experiments to promote a corpuscular theory of light, whereas his two critics both propagated a wave theory. There ensued various heated debates with Isaac giving as good as he got and the whole thing culminated in Newton threatening to withdraw from the Royal Society.

A couple of years later tempers had cooled down somewhat with Newton and Hooke once again on talking terms or better said on corresponding terms between Cambridge and London and in an attempt to ameliorate, Newton wrote the following in a letter to Hooke dated 5 February 1675:

What Des-Cartes [sic] did was a good step. You have added much several ways, & especially in taking the colours of thin plates into philosophical consideration. If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.

I’m not going to go into a lot of detail here but the expression standing on the shoulders of Giants was not original to Newton but in various forms has existed since at least the twelfth century, attributed by John of Salisbury (c. 1110–1180) in his Metalogicon in 1159 to Bernard of Chartres (died after 1124):

“Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature.”

There are other claims as to the origins of the concept. There is a wonderfully entertaining book on the saying by the sociologist Robert K Merton (1910–2003), On the Shoulders of Giants: The Post Italianate Edition(1965), which I heartily recommend for long train journeys or flights.

But let us return to the good Isaac and the question, if the phrase standing on the shoulders of Giants were to be applied to his Principia, if not Galileo, who would those giants be?

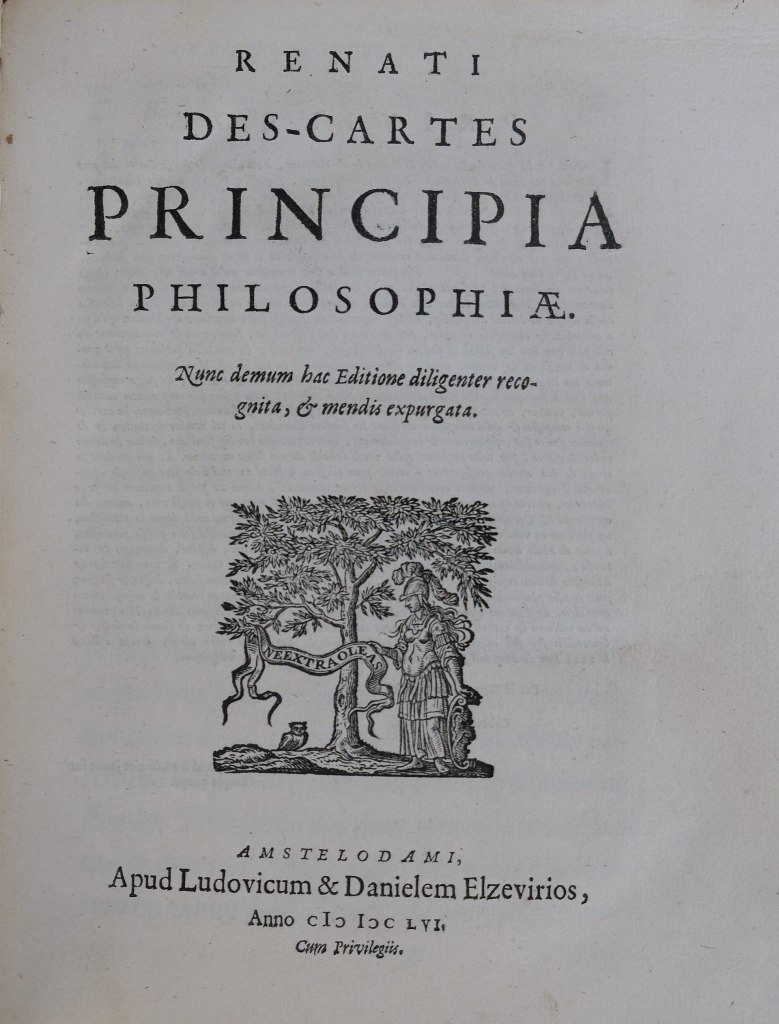

The first rather paradoxical answer is René Descartes (1596–1650).

Why paradoxical? It is paradoxical because the Principia is fundamentally an anti-Cartesian text starting with the title. Descartes book on the principles of nature is his Principia Philosophiae published in 1644, from which Newton borrowed the principle of inertia, his first law of motion. Newton deliberately borrowed the title but added Mathematica to show that his work was based on mathematics and not philosophical waffle like Descartes’ volume.

As a young man Newton had been a follower of Descartes, who was considered modern in opposition to the Aristotelian philosophy still taught at Cambridge. Descartes was one of the primary sources from which he learnt the new mathematics, although using the vastly expanded Latin edition of La Géométrie, produced by Frans van Schooten the Younger (1615–1660) rather than the French original. As I have pointed out on numerous occasions, it was van Schooten who first introduced Cartesian coordinates and not Descartes. But I digress.

As he matured, Newton distanced himself from Descartes vortex physics and the second of the three volumes of his Principia is devoted to a systematic deconstruction of Descartes theories. So, Descartes is very much a father of the Principia but in a negative not a positive sense. Just as Descartes was trying to refute Aristotle in his Principia, so Newton refuted Descartes in his.

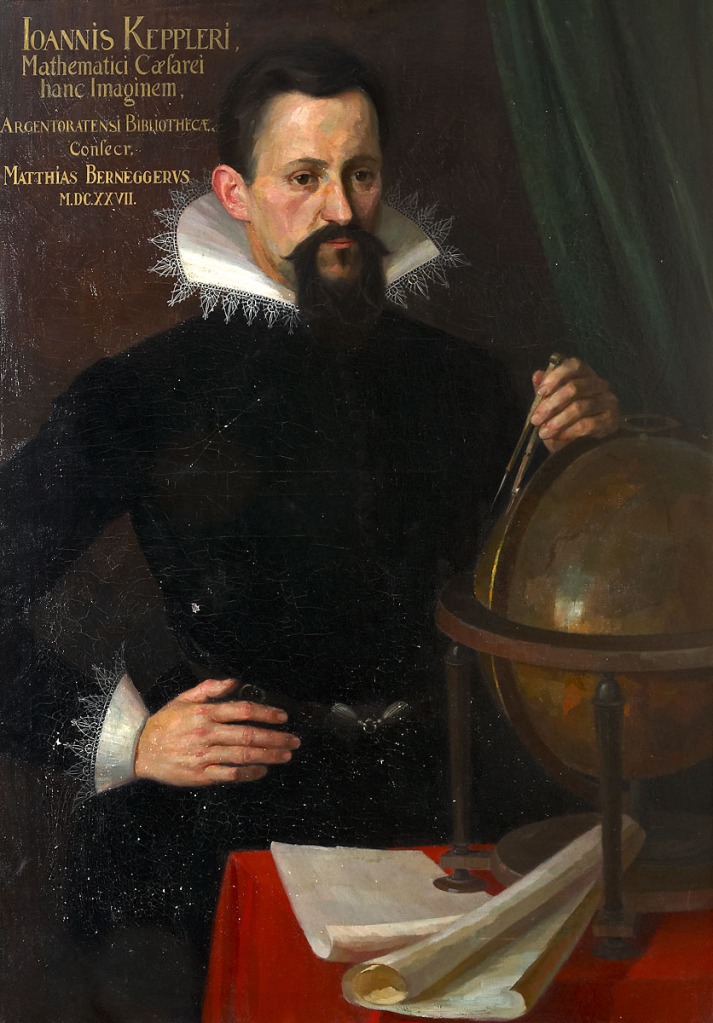

In a positive sense the shoulders on which the Principia is held aloft more than any others are those of Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), whose three laws of planetary motion build the backbone of Newton’s astronomy.

Interestingly, Newton claims the first two laws for himself, stating that Kepler had not proved them but he, Newton, had. What he is saying in that Kepler merely derived the laws empirically from Tycho’s data, whereas he derived them mathematically from his three laws of motion and centripetal force, to which I will return shortly. Newton then rather contradicts himself by crediting the third law to Kepler. Why contradicts? The third law is also an empirical law derived from observational data that had be shown to be valid for the then known planets in the cosmos, the moons of Jupiter and the moons of Saturn. This was important for Newton because using his laws of motion he proved that the third law and the inverse square law of gravity were mathematically equivalent. It followed from this proof that because the third law was empirically true the law of gravity must also be true.

Returning to the concept of centripetal force, Newton uses this throughout Book I of Principia and not the force of gravity is his mathematical derivation of the behaviour of masses in motion under the influence of forces. The concept of centripetal force or rather its inverse, centrifugal force was derived by Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695), our next set of shoulders, and published in his Horologium Oscillatorium Sive de Motu Pendulorum ad Horologia Aptato Demonstrationes Geometricae (The Pendulum Clock: or Geometrical demonstrations concerning the motion of pendula as applied to clocks) (1673) from whence Newton borrowed it.

From the same work Newton also took his second law of motion and Huygens’ correct determination of the acceleration due to the force of gravity, which Galileo had got wrong. It is fairly certain that others derived the inverse square law of gravity in the 1660s by combining Huygens work with Kepler’s third law. However, Newton claimed to have done the necessary derivation independently without borrowing from Huygens.

Huygens was also the first to astronomically survey Saturn with a telescope, discovering the largest of Saturn’s moons, Titan, in 1655. Giovanni Domenico Cassini (1625–1712) followed close on his heels discovering four more moons–Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Iapetus–between 1673 and 1686. Newton was eager to know whether the moons of Saturn provided another confirmation of Kepler’s third law.

The man who provided that information was Edmond Halley (1656–1742).

More than anybody else Halley carried Principia on his shoulders. It was Halley, who with his visit to Cambridge in August 1684 to ask Newton what the shape of planetary orbits would be if there were an inverse square law of gravity, provoked Newton to return to a problem he had abandoned almost twenty years earlier. It was Halley who urged Newton to write down his ideas for publication. It was Halley who persuaded The Royal Society to publish those ideas. It was Halley, who calmed the waves when Hooke provoked Newton by claiming the he and he alone should be credited with the discovery of the law of gravity, leading to Newton threatening to abandon Book III of Principia, The System of the World, the most important book. In the end, it was also Halley, who shouldered the cost of publishing the Principia, when the Royal Society ran out of money.

However, Halley also made scientific contribution to the book. As already noted above he supplied the important information that the moons of Saturn also conformed to Kepler’s third law. When Newton assumed that comets also conformed to the inverse squared law of gravity and Kepler’s laws, it was Halley who did the necessary research to confirm the assumption. The flight paths of comets played a major role in Book III.

Another set of shoulders on which the Principia rests are those of John Flamsteed (1646–1719), the Astronomer Royal. Without Flamsteed’s observational data accumulated since his appointment in 1675, Newton could not have written Book III. Flamsteed was also the first note that two comets were actually one and the same comet that had orbited the sun and returned. This was the point when the orbits of comets became important for a universal law of gravity. Although, it took Newton some time to accept that Flamsteed was right.

There are two giants, who never get mentioned in Principia, but who provide the scaffolding that permeates the entire book. There is a widespread myth that Newton used calculus to write Principia, he didn’t. Although he played a leading role in the development of analysis, Newton lost faith in its ability to provide solid proof, so all of the mathematics of Principia is classical Greek synthetic geometry, albeit somewhat updated by Newton. This means the geometry of Euclid (fl. 300 BCE) and because of the constant use of circles, ellipses, and parabolas the Conics of Apollonius of Perga (c. 240–c. 190 BCE). As to why Newton never mentions them, in his brief discussion of Dana Densmore’s Newton’s “Principia” : The Central Argument–Translations, Notes, and Expanded Proofs (Green Lion Press, 1995) I. B. Cohen writes:

Many readers will be grateful to Densmore for providing the missing steps and unstated assumptions in Newton’s constructions and often laconic proofs. They‚ will also be greatly aided by the geometric rules, methods, and procedures from Euclid and Apollonius that Densmore supplies, which Newton supposes readers will know.[1]

Returning to my opening paragraph, Newton, of course give Galileo credit every time that he uses either the laws of fall or the parabola law of projectile motion but in comparison to some of those I have sketched above his overall contribution to the Principia is relatively small and doesn’t really qualify him as a shouldering giant.

[1] Isaac Newton The Principia Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy: A New Translation by I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman assisted by Julia Budenz. Preceded by A Guide to Newton’s Principia by I. Bernard Cohen p. 276