People writing about the history of science tend not to think of their subjects as party animals. Science is a serious topic, scientists are serious scholars, party time is not really considered as part of the picture. However, some scientists have been notorious party animals and one of those was Charles Babbage. This wasn’t always the case but was something that first developed when he was already forty years old.

School; Charles Babbage (1792-1871) ; National Trust, Dudmaston; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/charles-babbage-17921871-132467</p>

<p> ” data-medium-file=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host-10.jpg” data-large-file=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host-12.jpg?w=500″ width=”850″ height=”1024″ src=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host.jpg” alt class=”wp-image-11606″ srcset=”https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host.jpg 850w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host-9.jpg 125w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host-10.jpg 249w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host-11.jpg 768w, https://wolfscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/christmas-trilogy-2023-part-2-charles-the-genial-host-12.jpg 996w” sizes=”(max-width: 850px) 100vw, 850px”></a><figcaption class=) British (English) School; Charles Babbage (1792-1871) circa 1820; National Trust, Dudmaston; via Wikimedia Commons

British (English) School; Charles Babbage (1792-1871) circa 1820; National Trust, Dudmaston; via Wikimedia CommonsIn 1814, much to the displeasure of his father, Babbage got married on graduating from Cambridge to Georgina Whitmore at the age of twenty-three. His father didn’t approve because he didn’t have any form of employment and was still dependent on his rich father to provide him with an allowance. The couple lived initially in Devon moving to London in 1815. The couple had eight children of which only four survived childhood. 1827 was a black year for Babbage as both his father and his wife died. He packed up and left London, going on an extended journey around the continent.

Returning to London in 1828, he was now a very rich man having inherited a fortune from his father. He bought a new house, 1 Dorset Street, Marylebone, and it is here in the 1830s that he became a notorious lion of the London social scene known for his extravagant soirées.

Harriet Martineau (1802–1876) was a writer, social theorist, abolitionist, who had moved to London in 1832. Darwin’s sister, in a letter, wrote, she is “now a great Lion in London, much patronized by Ld. Brougham who has set her to write stories on the poor Laws” and recommending Poor Laws and Paupers Illustrated inpamphlet-sized parts. They added that their brother Erasmus “knows her & is a very great admirer & everybody reads her little books & if you have a dull hour you can, and then throw them overboard, that they may not take up your precious room.” Martineau, herself, wrote in a letter, “All are eager to go to his [Babbage’s] glorious soirées.”

Some readers might ask, what is a soirée?

In the 18th century, in France and England, it became fashionable for wealthy, well married ladies who had a residence “in town” to invite accomplished guests to visit their home in the evening, to partake of refreshments and cultural conversation. Soirées often included refined musical entertainment, and the term is still sometimes used to define a certain sophisticated type of evening party. (Wikipedia)

In this case we have a very wealthy host, although his daughter Georgiana (1818–1834) initially functioned as hostess, and the dimensions of Babbage’s soirées certainly reflected his wealth. These affairs which regularly took place on Saturday evening had between two and three hundred guests from all sections of the London high society. Celebrities, civil dignitaries, authors, actors, scientists, bishops, bankers, politicians, industrialists, and socialites converged for gossip, intrigue, and the latest in science, literature, philosophy, and art.

The author Charles Dickens (1812–1870), who was friends with Babbage, had been known to attend and it is thought that the character Daniel Doyce in his novel Little Dorrit (1855–57) was based partially on Babbage and partly on his engineer, Joseph Clement (1779–1844).

Dickens also joined Babbage in his crusade against the noise pollution of the street musicians.

The geologist Charles Lyell (1797–1875) was a frequent attendee.

Lyell is noted for his influence on the young Charles Darwin (1809–1882), Darwin returned to England from his voyage on the Beagle in 1836. In the following year he informed his sister that Charles Lyell was insisting he hurry on up to London. He “wants me to be up on Saturday for a party at Mr Babbage.” Darwin halfheartedly complained. Lyell say Babbage’s parties are the best in the way of literary people in London–and that there is a good mixture of pretty women.”[1] Lyell was obviously matchmaking for Darwin as he was already happily married.

Babbage’s parties brought together levels of society usually socially segregated. Female members of the titled played whist with the wives of experimenters and fossil hunters, while on the dance floor the attractive young daughters of noblemen aristocracy whirled with the unmarried scientists. Lyell told Herschel that “[Babbage] has done good, and acquired influence for science by his parties and the manner in which he has firmly and successfully asserted the rank in society due to science.”[2]

Amongst a long list of prominent guests was the Scottish, mathematician, science writer, and translator Mary Somerville (1780–1872) famous for her popular translation of Laplace’s Mécanique Céleste, who was an important correspondent of Babbage’s with whom he discussed his vision for the Analytical Engine.

To provide sustenance for the long night ahead, a table would be laid with punch, cordials, wine, sand Madeira; tarts; fruits both fresh and dried; nuts, cakes cookies, and finger sandwiches. The grandest repasts would include oysters, salads, croquettes, cold salmon, and various fowls.[3]

As well as dancing there were entertainments such as novelists reading their latest work, tableau vivants, scientific demonstrations, astronomical telescope observations out on the lawn, or Babbage displaying the early photographs of his friend William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877).

A hight point of the entertainments was Babbage presenting his guests with his passion for automation and the computer. He would first present his silver danseuse, the story of which he relates in his autobiography:

“During my boyhood my mother took me to several exhibitions of machinery. I well remember one of them in Hanover Square, by a man who called himself Merlin. I was so greatly interested in it, that the Exhibiter remarked the circumstance, and after explaining some of the objects to which the public had access, proposed to my mother to take me up to his workshop. Where I would see still more wonderful automata. We accordingly ascended to the attic. There were two uncovered female figures of silver, about twelve inches high.

[…]

The other silver figure was an admirable danseuse, with a bird on the fore finger of her right hand, which wagged its tail, flapped its wings, and opened its beak. This lady attitudinized in a most fascinating manner. Her eyes were full of imagination, and irresistible.

Charles Babbage, Passages from The Life of a Philosopher, Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, London, 1864 p. 17

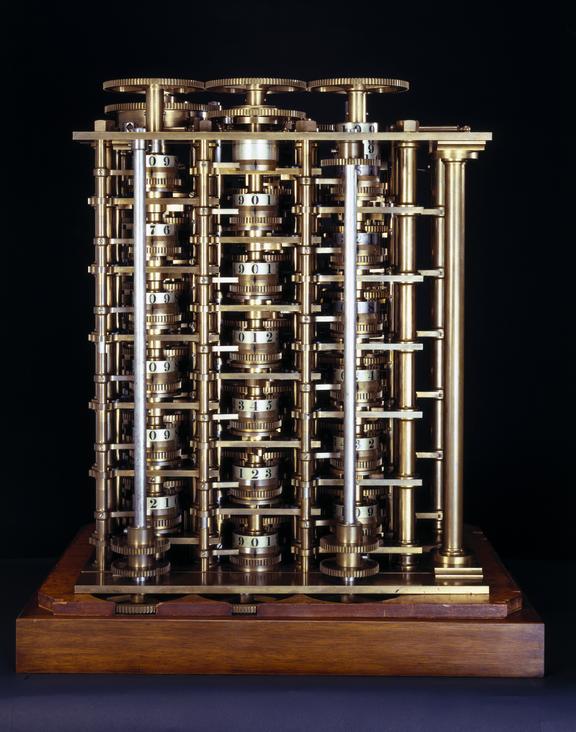

In 1834, Merlin having died in 1803, Babbage acquired the silver danseuse restored it and had new clothes made for it. Having charmed he guests with his mechanical danseuse, Babbage would move on to the small working model of his Difference Engine which he had his engineer Joseph Clement (1779–1844) construct in 1832.

I have described what happened next in an early blog post, which I will now quote:

Babbage argued by analogy, he describes the possibility of a computer programme (not the terminology that Babbage uses by the way) that generates the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, … up to and including 100,000,001 but then instead of producing the number 100,000,002 as expected jumps to 100,010,002, continuing the series 100,030,003; 100,060,004; 100,100,005; 100,150,006; 100,210,007 … and so forth. Babbage states that the law generating the series has changed at the jump. The expected numbers being exceeded by the series 10,000, 30,000, 60,000, 100,000, 150,000 … and so on this being the series of triangular numbers 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, … multiplied by 10,000.

Babbage goes on to explain that the operator does not need to interfere with the calculating engine (he is of course thinking of his own Difference Engine) at this point but can pre-programme it from the beginning to make the change at the given juncture.

Unlike Whewell’s God who has to intervene in his own laws of nature with miracles to explain the presence of new species in the geological record Babbage’s mathematical God can pre-programme his laws of nature to change at the required point in time thus pre-programming his miracles at the point of creation.

Babbage actually programmed one of the calculating units of his Difference Engine to perform a miracle of the type described here, which he then demonstrated to guests at the soirees he held at his home in London.

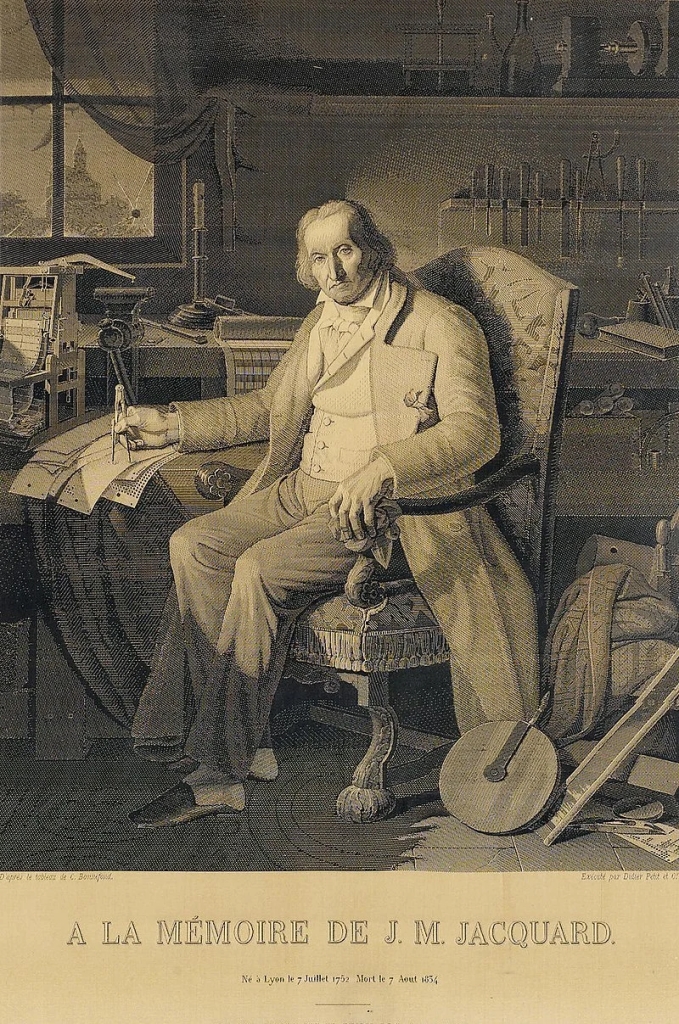

Towards the end of the 1830’s he added another act to his automata/calculator party turn. He had acquired, for the then extraordinary sum of £800, one of the woven-in-silk portraits of Joseph Marie Jacquard (1752–1834), whose system of punch card programming Babbage intended to borrow for his planned Analytical Engine.

Following the demonstration of the miracle working Difference Engine, Babbage would unveil the portrait and challenge his assembled guests to guess how it had been produced.

As Lyell had explained to Herschel, Babbage knew how to sell science and technology with showmanship.

[1] Laura Snyder, The Philosophical Breakfast Club, Broadway Paperbacks, 2011 p. 189 A brilliant book about the friendship between Babbage, William Whewell, John Herschel and Richard Jones that I heartily recommend

[2] Snyder p. 190

[3] Snyder p. 191