Almost Everyone Carries Epstein-Barr Virus, But It May Hold the Key to Understanding Multiple Sclerosis

Almost everyone carries Epstein-Barr virus. It causes the miserable few weeks of mononucleosis in adolescence, the swollen glands and bone-deep fatigue that keep teenagers home from school, then settles into immune cells for life, usually without further complaint.

Yet for decades, researchers have noticed something troubling: people who develop multiple sclerosis almost always carry this virus, while those rare individuals who escape infection almost never get the disease. The puzzle was never whether the virus played a role, but how a near-universal infection could spark a condition that strikes fewer than one in a thousand.

New research published in Cell offers a concrete answer. Teams at the University of Basel, University of Zurich, and Karolinska Institutet have traced a precise sequence of immune events that can lead from ordinary viral infection to the first lesions in the brain. The findings suggest that MS may begin not with a dramatic immune assault, but with a quiet failure of the body’s safety mechanisms in a place where such failures are least forgiving.

When the Brakes Fail

The immune system normally polices itself with care. B cells that mistakenly recognize the body’s own tissues are flagged for destruction before they can cause harm. The new study shows that Epstein-Barr virus can override this safeguard. One viral protein mimics an approval signal that tells self-reactive B cells to survive when they should die. In effect, the virus lets dangerous cells ignore the immune system’s stop signs.

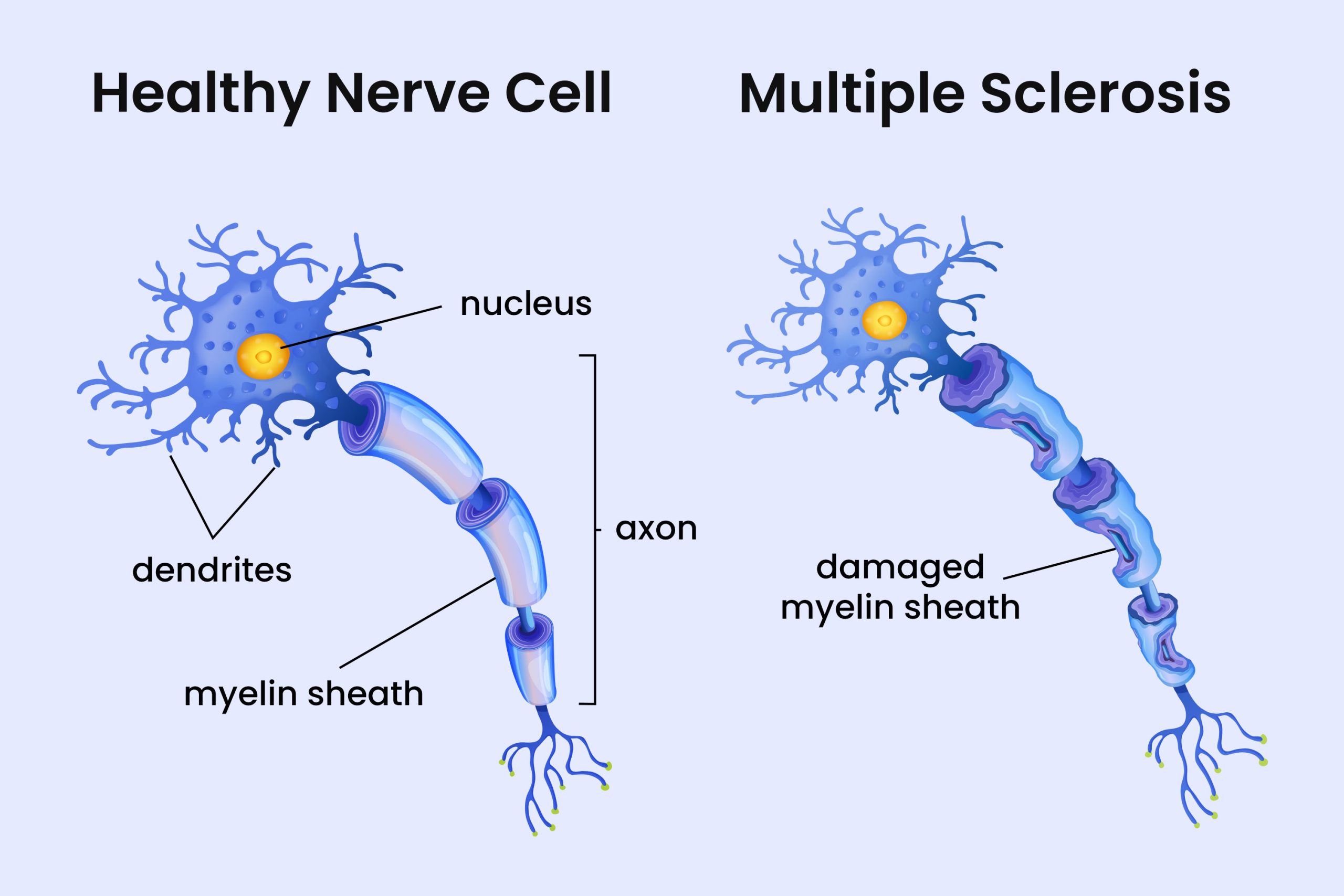

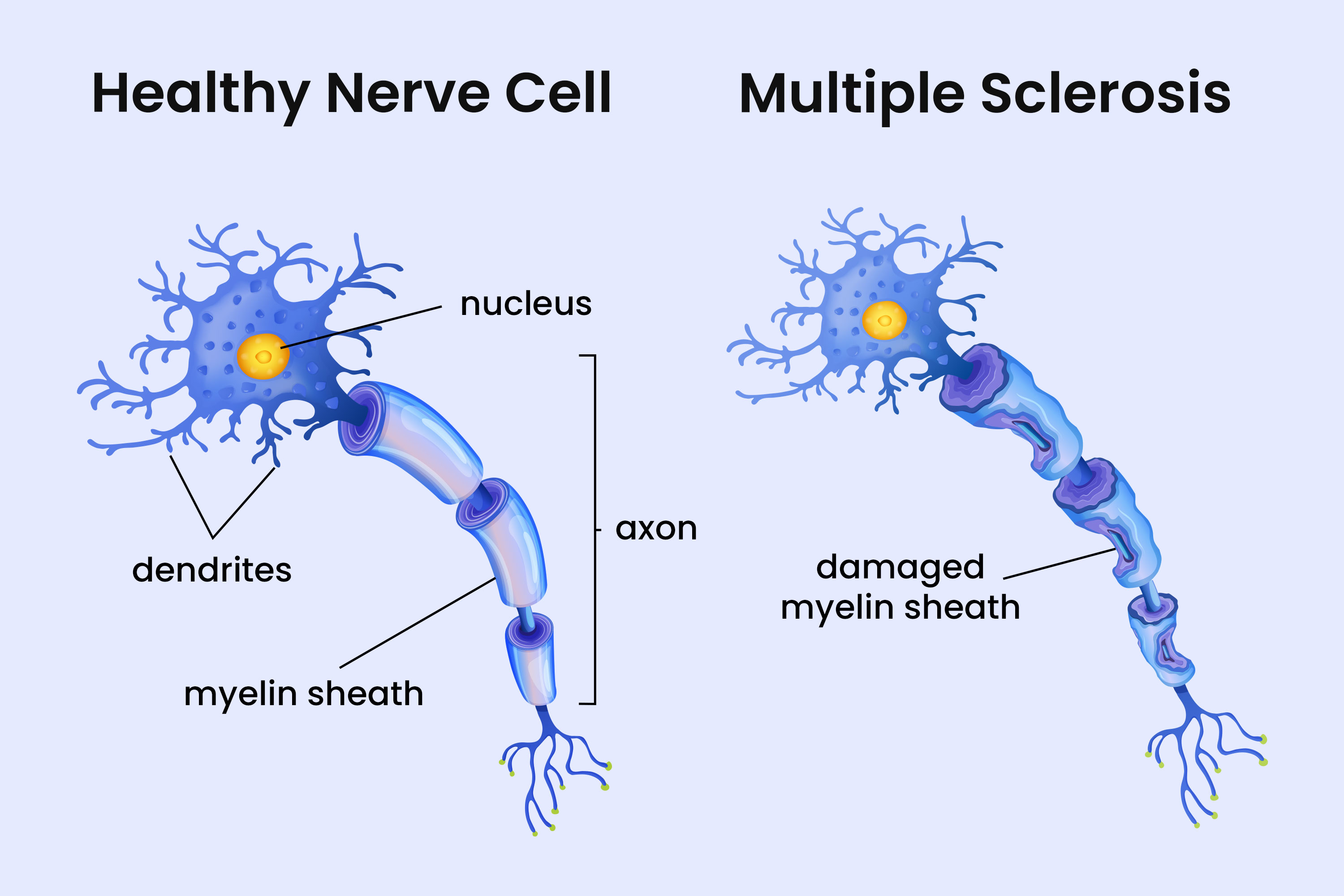

The brain is an unusual environment for immune activity. During infections or inflammation, B cells can briefly cross into brain tissue, usually without consequence. But when virus-infected B cells carrying this survival advantage enter the brain, the balance tips. In mouse models, these rogue cells captured myelin antigens, the proteins that make up the fatty white insulation around nerve fibers, and triggered localized damage. The lesions closely resembled the earliest pathology seen in human MS patients, the kind of small, focused injury that might go unnoticed for years.

The researchers also found evidence of molecular mimicry, where the immune system confuses viral proteins with the body’s own. In people carrying a genetic risk factor known as HLA-DR15, this confusion becomes more likely. T cells recruited to fight the infection may accidentally recognize brain proteins as the enemy. The virus even forces infected B cells to produce a myelin protein that acts as a homing beacon, drawing these confused T cells toward nerve tissue.

“The role of EBV in MS has been quite mysterious for a long time. We have identified a series of events including EBV infection that has to happen in a clearly defined sequence to cause localized inflammation in the brain.” – Tobias Derfuss, University of Basel

A Spark, Not the Whole Fire

The authors are careful to note that this pathway does not explain every case of MS. The disease likely has multiple routes, and other studies published alongside this work highlight additional mechanisms involving cross-reactive T cells and genetic susceptibility. What this research provides is a detailed map of one initiating sequence, the kind of spark that might smolder for years before a patient notices numbness in a fingertip or an episode of blurred vision.

By understanding the earliest moments of the disease, scientists can now look for ways to intervene before chronic inflammation takes hold. This might eventually mean vaccines designed to prevent severe Epstein-Barr infections in childhood and adolescence, or treatments that target the confused immune cells without dismantling the body’s defenses entirely. The shift matters because current MS therapies mostly manage symptoms and slow progression; they cannot undo damage already done. If doctors could identify patients at risk and act before the first lesion forms, the calculus of treatment would change entirely.

For now, the findings confirm that while nearly everyone hosts this virus, its ability to slip past the immune system’s checkpoints is the key to one of medicine’s stubborn mysteries. The spark, it turns out, is not the infection itself but what happens when the body’s own defenses fail to notice that something has gone wrong.

[Cell: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.12.031](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.12.031)

There’s no paywall here

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!