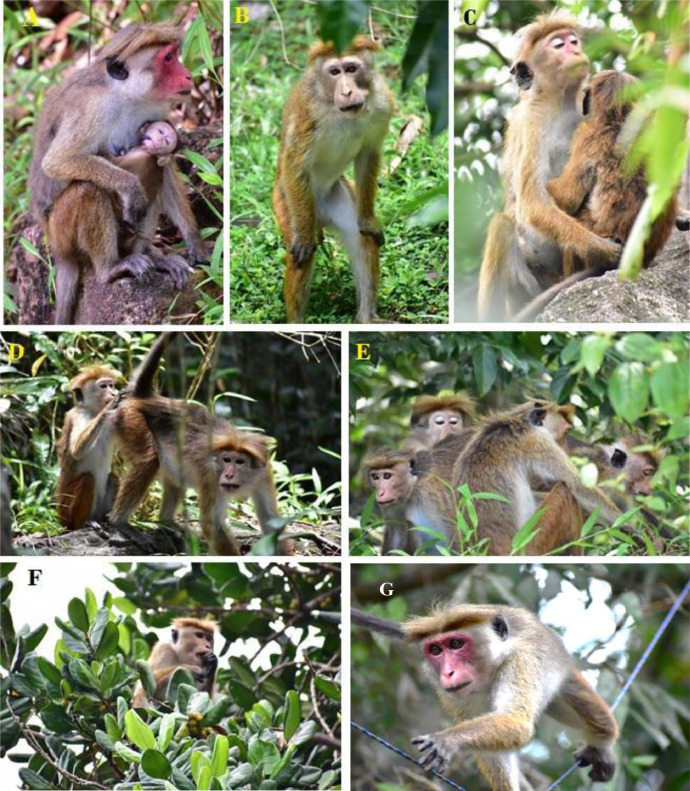

Observe any group of macaques for a while and you’ll catch sight of it: males engaging with males, females making contact with females. Same-sex sexual activities have been recorded in approximately 1,500 species, yet researchers have found it challenging to understand why this behaviour continues to exist. A recent study covering nearly 500 primate species provides the most comprehensive insight to date, suggesting that the reasons are more closely tied to environmental conditions and the intricacy of their social structures than to genetics.

Scientists from Imperial College London gathered data on 491 non-human primate species, identifying confirmed instances of same-sex sexual behaviour in 59 of these. The occurrences varied from infrequent (approximately once every 300 hours of observation in common marmosets) to quite common (almost three times each hour in Japanese macaques).

They posed a straightforward question: what commonalities exist among those 59 species? The trends that unfolded were remarkable. Primates inhabiting arid environments with limited food resources and higher predator presence were substantially more inclined to partake in same-sex mounting and genital interaction. Additionally, species exhibiting marked size disparities between males and females, longer life spans, and (crucially) more complex social hierarchies also demonstrated this behaviour.

When Challenges Arise, Connections Strengthen

The reasoning is easy to follow. In difficult settings, survival hinges on collaboration. Gathering food together, watching for predators collectively, and caring for young collectively all necessitate trust. In primate communities, trust is fostered through physical interaction. While grooming is the most apparent illustration, same-sex mounting seems to fulfill a similar purpose by alleviating post-conflict stress and solidifying alliances that are beneficial during food shortages or when rivals loom.

Take the golden snub-nosed monkey, which braves harsh winters in the mountains of central China. Researchers have noted that same-sex interactions peak when temperatures fall and food is scarce. Or consider bonobos, known for their sexual openness, who engage in genital rubbing between females to resolve disputes and enhance camaraderie. Researchers observe that genital contact following conflicts in bonobos is linked to diminished tension, a short-term effect that may aid reconciliation and reinforce partnerships. In both examples, same-sex behaviour is not just an oddity; it acts as social adhesive.

Established hierarchies present unique challenges. In male rhesus macaques, same-sex mounting aids individuals in managing aggression and fluctuating dominance. Males that participate in this behaviour are more likely to create alliances and back one another in competitive scenarios. This trend persists across species: solitary primates showed considerably less same-sex behaviour compared to those living in groups, and highly stratified species exhibited significantly more. When status is significant, it seems the capacity to build allies is equally crucial.

“Same-sex sexual behaviour is a vital aspect of numerous non-human primate societies, and it appears to aid these animals in bonding and maintaining group cohesion,” stated Vincent Savolainen, director of Imperial College’s Georgina Mace Centre for the Living Planet and the lead author of the study.

Genetics Have a Minor Influence

Previous research on rhesus macaques suggested that same-sex behaviour is roughly 6 percent heritable, indicating that the majority of variation stems from environmental and experiential factors. The new study corroborates this. Through structural equation modeling, the researchers concluded that ecological stressors shape life history characteristics (such as lifespan, body size, and level of sexual dimorphism), which subsequently influence social constructs. Social complexity then directly facilitates same-sex behaviour. Both environment and life history are important, but they operate indirectly, mediated by the needs associated with group living.

The researchers emphasize what their results do not imply. They focused on behaviour in monkeys and apes, not human sexual orientation or identity. Evolutionary patterns in different species cannot be used to justify or explain the entire spectrum of human experiences, and the authors explicitly disavow any potential misuse of their findings to undermine LGBTQ+ lives. What the study indicates is that same-sex behaviour in primates is neither uncommon nor abnormal. It is observed across lemurs, New World monkeys, Old World monkeys, and apes, suggesting deep evolutionary origins and likely multiple independent occurrences.

For those who view animal sexuality merely as a function of reproduction, the evidence from primates offers humbling insights. It turns out that sex has always transcended baby-making. It’s also about forming friendships.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02945-8

<div class="code-block code-block-