You enter the kitchen and lose track of your purpose. A well-known name lingers just beyond your grasp. The keys to your car are found in the fridge. These minor forgetfulness episodes occur to nearly everyone after reaching a certain age, and most attribute them to “aging.” But what truly transpires within the brain when memory begins to falter?

A comprehensive new investigation provides some insights, revealing a complexity beyond merely attributing it to a deteriorating brain. Researchers gathered data from 13 extensive studies across Europe and North America, analyzing over 10,000 brain images and 13,000 memory assessments from 3,737 cognitively sound adults. This remarkable scale enabled scientists to uncover trends that smaller studies had overlooked for years.

The primary discovery challenges a neat assumption. Memory deterioration does not align neatly with brain contraction. Rather, the correlation is defiantly nonlinear. Individuals whose brains decreased in size at an average or slower rate exhibited surprisingly minimal memory issues. However, once atrophy surpassed a certain threshold, cognitive effects accumulated rapidly. Imagine it as a roof that withstands years of weather, then suddenly begins to leak everywhere once the shingles deteriorate past a critical juncture.

More Than Just the Hippocampus

For a long time, memory studies have concentrated on the hippocampus, that diminutive, seahorse-shaped structure nestled deep within the brain. It lives up to its reputation; the fresh analysis affirmed it’s the region most closely associated with memory decline. Yet the narrative doesn’t end there. The researchers identified nineteen separate brain areas, including the amygdala and thalamus, where shrinkage correlated with declining recall. Memory, it turns out, relies on an extensive network, rather than a single primary player. When numerous components of that network begin to diminish simultaneously, the entire system becomes vulnerable.

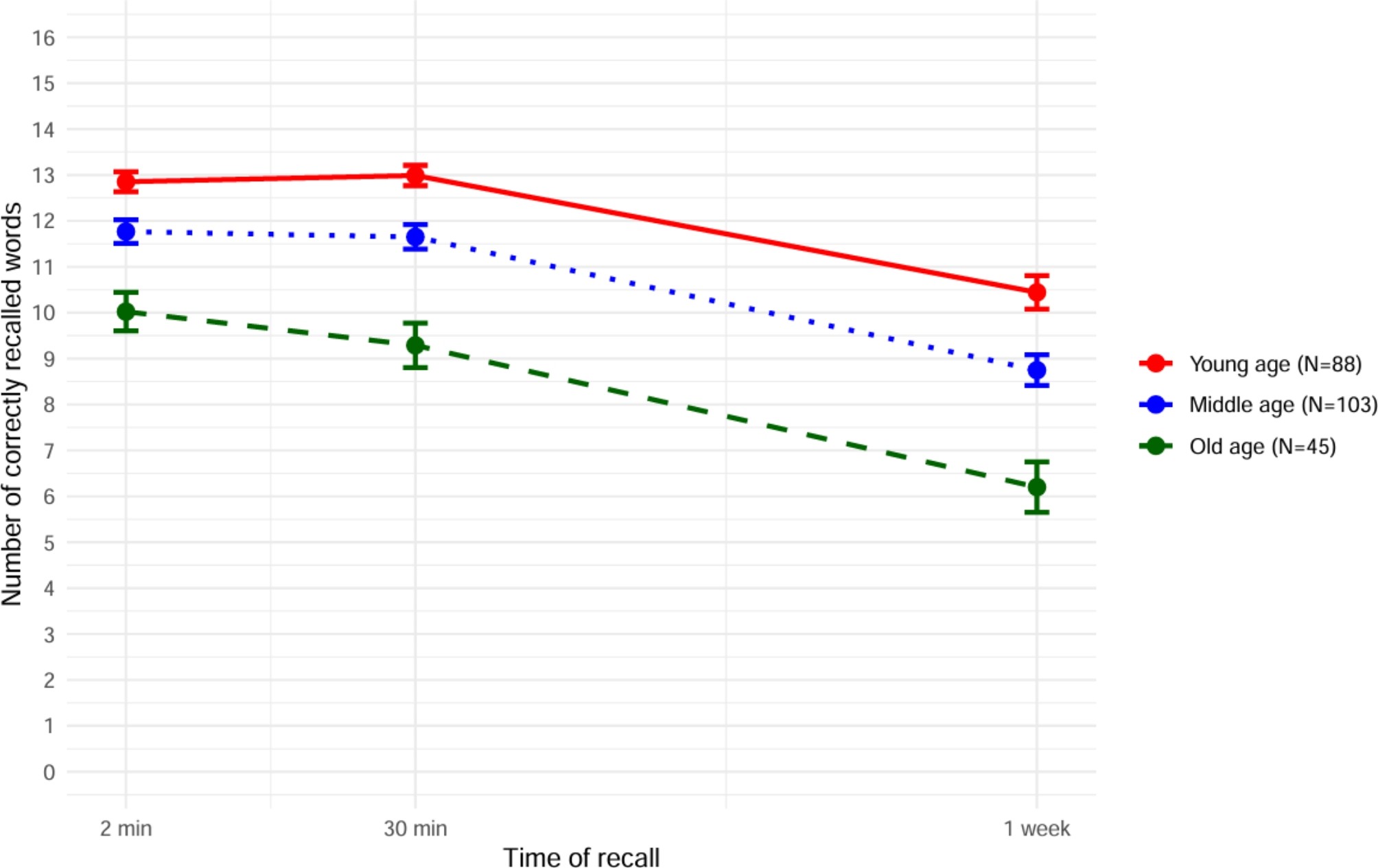

Age itself serves as a kind of volume control. Among participants in their fifties, the link between brain shrinkage and memory loss was barely discernible. By the time individuals reached their eighties, it had become unmistakable. The older the brain, the less adaptability it possesses to withstand additional wear.

Genes Accelerate the Decline, but Don’t Alter the Rules

What of genetic predisposition? Carriers of the APOE ε4 gene, the strongest known hereditary predictor of Alzheimer’s disease, did indeed exhibit quicker rates of brain shrinkage. But here’s the unexpected result: the gene did not transform how atrophy impacted memory. Both carriers and non-carriers followed the same fundamental pattern. Genetics may influence the speed of decline, but the biological principles linking brain shrinkage to memory degradation appear consistent across the board.

“These findings indicate that memory decline with aging is not solely dependent on one area or one gene — it reflects a wide biological susceptibility in brain structure that accumulates over many years.” – Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Marcus Institute for Aging Research

Since every participant in this study was cognitively healthy, the results suggest a process occurring long before any formal diagnosis. The susceptibility is already developing, silently, in brains that appear perfectly healthy on the outside. This reframing is significant. It implies that safeguarding memory in older age may involve less about bolstering a single weak area and more about enhancing the brain’s resilience across the board, years or even decades before difficulties surface.

None of this implies that memory loss is unavoidable, or that a forgotten name indicates looming disaster. Most individuals will never face dementia. Brains vary. Some remain incredibly robust. However, recognizing that memory is dependent on a vast network of aging structures, not just one frail area, alters how researchers approach intervention. The objective is not to salvage a single failing component. It’s to maintain the entire system functioning together for as long as feasible.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66354-y](https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66354-y)

No paywall here

If our reporting has educated or motivated you, please think about making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of size, enables us to continue providing accurate, engaging, and reliable science and medical news. Independent journalism necessitates time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep revealing the stories that matter most to you. Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for supporting us!