The most ancient conflict on our planet, the struggle between bacteria and the viruses that target them, has persisted for billions of years. This battle unfolds within your intestines, in the soil, and in every small body of water. Recently, experiments conducted on the International Space Station have revealed that this interaction changes when gravity is absent.

A study featured in PLOS Biology launched the bacteriophage T7 along with its preferred host, Escherichia coli, into space to observe the effects of altered conditions. Bacteriophages, commonly known as phages, are viruses that infect and eliminate bacteria. On Earth, the interaction between phages and their hosts is an unyielding arms race: bacteria develop defenses, phages counter with adaptations, and this cycle continues at an intense pace. Under standard conditions, T7 can infect and eradicate E. coli in less than 30 minutes. However, the researchers discovered that this process takes significantly longer in microgravity.

The explanation is surprisingly straightforward. In the absence of gravity, there is no convection, no settling, and no gentle movement of particles through fluids. Consequently, phages and bacteria encounter each other only through slow, limited diffusion. In Earth-based experiments, the quantity of viruses skyrocketed within two to four hours. However, no activity was observed at those early intervals in the space samples. Nevertheless, after 23 days, the phages were successful. While microgravity slowed their offensive, it did not prevent it entirely.

Varied pressures, varied mutations

The most astonishing aspect of the study emerged from analyzing the surviving specimens. After over three weeks, both phages and bacteria had developed new mutations, which differed significantly from those observed in Earth controls. The phages that traveled to space exhibited changes in tail proteins that aid in attaching to bacterial surfaces. Meanwhile, the bacteria evolved modifications in genes associated with their outer membranes and stress responses, a classic defensive strategy for cells aiming to fend off viruses.

Next, the researchers implemented an innovative approach. They employed a method known as deep mutational scanning to examine 1,660 variations of the phage’s receptor binding protein, the molecular mechanism it utilizes to attach to bacteria. The variants that flourished in microgravity appeared entirely distinct from those that thrived on Earth. The selective pressure exerted by microgravity seems to favor a different array of genetic solutions.

Applying insights from space to medicine

This is where the research transitions from mere curiosity to potential clinical implications. The team utilized the successful mutations from space to create new phage variants. They subsequently assessed these “microgravity-informed” phages against two types of uropathogenic E. coli, which are responsible for persistent urinary tract infections and show resistance to the original T7 phage. The variants developed from space successfully infected and eliminated the bacteria that previously resisted the wild-type virus.

“Microgravity selections revealed novel genetic determinants of fitness and enabled efficient navigation of sequence space to find improved phage variants.”

The researchers are cautious not to exaggerate their claims. Experiments on the ISS involve inevitable limitations such as freeze-thaw cycles, delays in processing, and fewer time points than desired. They also note that some authors have stakes in a phage therapeutics venture, underscoring that the route from orbit to pharmacy includes commercial considerations.

Nonetheless, the overarching perspective remains valid. Phage therapy, which employs viruses to eliminate drug-resistant bacteria, has struggled due to the challenges in engineering phages capable of targeting new strains. This study indicates that microgravity functions as a distinct laboratory, revealing mutational opportunities obscured by Earth’s constant gravitational pull. For those concerned about antibiotic resistance, this is a valuable insight to possess.

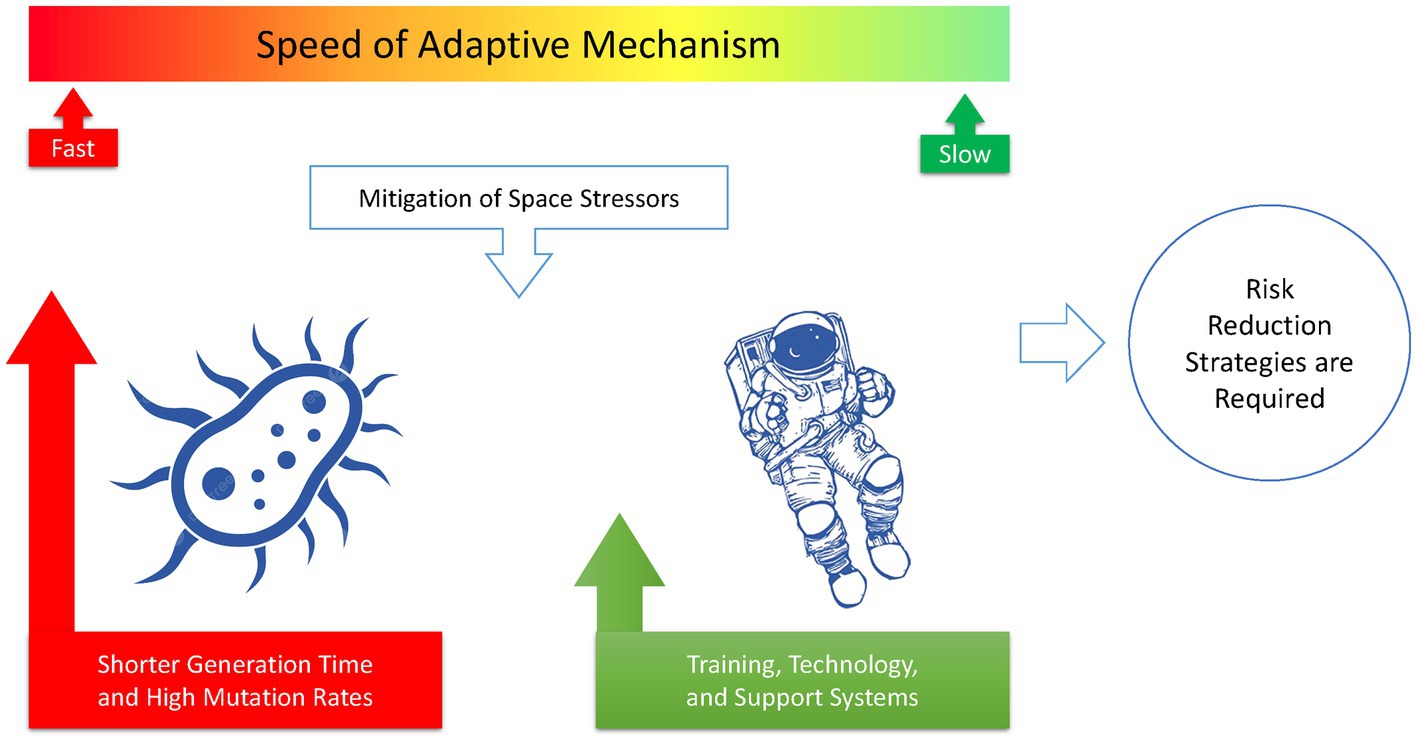

Additionally, there is a subtler lesson for long-term space missions. Microbial communities on spacecraft are not merely Earth organisms in a different location. When the dynamics of mixing and transport vary, so do the evolutionary pressures. Phages and bacteria may embark on trajectories not predicted by terrestrial experiments. Understanding these changes is crucial for astronauts who spend extended periods in orbit or beyond. The microscopic arms race persists in space, albeit under different regulations.

PLOS Biology, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3003568

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider contributing. Every donation, regardless of size, empowers us to keep delivering accurate, engaging, and reliable science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support helps us continue uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge