Every moment of every day, wherever a river feeds into the ocean, energy disappears. The freshwater meets the saltwater, their salt levels balance out, and the chemical potential that existed between them dissipates as excess heat. No turbine harnesses it. No grid transports it away. On a global scale, this unseen loss totals approximately 2,400 gigawatts of continuously wasted energy, enough to match the world’s complete electricity usage.

Scientists have been aware of this untapped source since the 1950s, and they refer to it as blue energy. The idea is strikingly straightforward. Separate salty water from fresh using a membrane that permits only specific ions to pass through, and the ensuing charge difference produces voltage, similar to a battery. However, decades of work have confronted an irritating dilemma: membranes that permit quick ion flow tend to struggle with properly sorting them, while those that are highly selective restrict the current flow.

Now, a team at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) has discovered a clever solution, drawing inspiration from the cells within your own body. Yunfei Teng, Tzu-Heng Chen, and colleagues in Aleksandra Radenovic’s Laboratory of Nanoscale Biology layered the insides of tiny silicon-based nanopores with lipid bilayers, the same fatty double-layered membranes that encase every living cell. Published today in Nature Energy, their findings suggest that this biological enhancement could bring blue energy closer to a feasible engineering project.

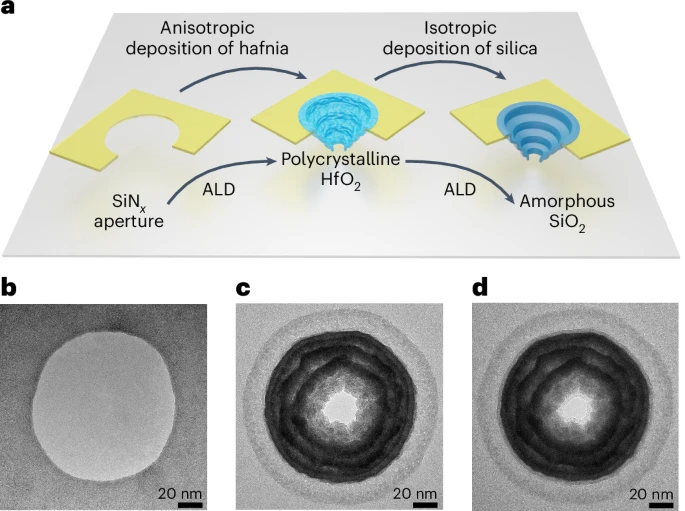

The challenge they were addressing is quite nuanced. Solid-state nanopores, created in durable materials like hafnium oxide through semiconductor fabrication techniques, provide exceptional control over pore shape. You can construct them precisely 25 nanometers wide and fit hundreds of millions into a square centimeter. However, controlling how the liquid behaves once it enters is much trickier.

Lipid bilayers alter this dynamic in two concurrent ways. Their charged headgroups (the team employed mixtures of DOTAP, a positively charged lipid, and DOPC, a neutral lipid) amplify the surface charge density to levels that far exceed what bare solid-state materials can achieve. At a 75 percent DOTAP blend, the charge density reached 0.4 coulombs per square meter, approximately double that of graphene or boron nitride nanotubes, which have been favored in the nanofluidics field for years. But here’s the ingenious part. At such elevated charge densities, a phenomenon known as hydration lubrication comes into play. Charged surfaces in aqueous environments trap a thin layer of water molecules, possibly just a few molecules thick, that clings via electrostatic attraction and functions as a molecular lubricant. This effect has been well documented in tribology studies on mica, where it yields friction coefficients below 0.0002, but it had never been intentionally utilized to improve osmotic energy harvesting before.

In traditional solid-state materials, charge and friction are locked in a conflicting relationship: increasing one tends to elevate the other, as denser surface charges result in greater electrostatic resistance to the flowing liquid. The lipid bilayer separates them. Its hydration layer lessens wall friction while the charged headgroups heighten ion selectivity, and computer simulations conducted by the team illustrated that beyond a slip length of about 20 nanometers, fluid velocity at the pore wall actually surpasses that in the middle of the channel. This is an unusual reversal of typical flow patterns. It is also what drives the improvements in performance.

Inserting lipid bilayers inside nanopores just 24 nanometers wide is, as one might expect, quite complex. The team employed electrically charged liposomes, spherical lipid bubbles around 100 nanometers in diameter, and propelled them toward the pore openings using an applied voltage. The forces of electrophoresis and electroosmosis collaborated to direct the liposomes into the stalactite-shaped nanostructures, where the tight space compressed and collapsed them, spreading a single bilayer coating (about 4 nanometers thick on each side) across the inner surfaces. The team monitored everything in real-time by observing changes in ionic current.

When scaled up to a membrane containing roughly 1,000 of these coated nanopores arranged in a hexagonal pattern extending 20 micrometers, the system yielded a power density of approximately 51 kilowatts per square meter when assessed from the active pore area alone. Under conditions replicating a genuine river-meets-ocean environment, the measure fell to about 41 kilowatts per square meter. Even when normalized to the total membrane area, which considers the inactive space between pores, the output reached around 15 watts per square meter; roughly two to three times the performance currently achieved by existing polymer membrane technologies. “Our research combines the advantages of two primary methods for osmotic energy harvesting,” states Radenovic: “polymer membranes, which inspire our high-porosity design; and nanofluidic devices, which we utilize to create highly